New month, same old stuff. The virus is still on a coast-to-coast rampage, the economy is still stumbling through the fog and Congress is still deadlocked over how to help. And asset markets of all stripes are still in full-on rally mode. Are things looking great? They must be, since everything from blue-chip US mega-caps to small caps and emerging markets are going gangbusters. Are things looking pretty terrible? They must be, since yields on 10-year Treasuries are back down to where they were at the height of the March panic, while inflation-protected TIPS yields are below minus (yes, minus) one percent. Are we in for a resurgence of inflation? We must be, because gold surged over $2,000 per ounce for the first time ever this week.

So who’s right? Or is there some rational reason for everything to be rallying at the same time?

Risk On, Risk Off

Here’s a snapshot of a world where assets that usually signal a flight to safety happily coexist with those typically favored by risk-seekers.

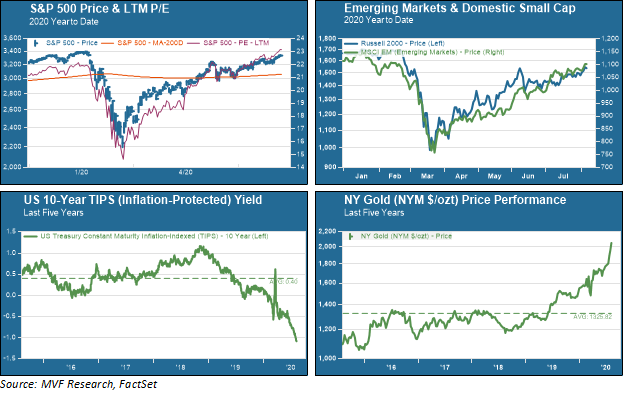

While the driving force of the rally in equities has come from the large cap growth stocks we talked about in last week’s column, making this the shortest bear market in S&P 500 history (top left chart), other equity asset classes have surged as well, including small caps and emerging markets (top right chart). Normally when these “risk on” asset classes do well it suggests an optimistic view of the world filled with expectations of dynamic growth in sales, earnings and economic output.

That view is out of step with what the bottom two charts seem to be telling us. Government securities tend to do well when investors see pain and trouble down the road. Yields on US Treasuries have fallen significantly in the past several weeks as our abject failure to contain the coronavirus became clear and sent the much-ballyhooed “reopening” back into reverse. TIPS, which are inflation-protected Treasuries (lower left chart) are now trading at record low yields of minus 1.08 percent. Gold (lower right chart) is another “risk off” asset, traditionally seen as a hedge against inflation. The shiny commodity also surged into record territory this week, trading over $2,000 per ounce.

TINA’s World

While the “everything rally” seems strange on its face, there is a driving force that explains at least part of it. That driving force is negative interest rates. A sizable chunk of securities in global fixed income markets trade at negative nominative yields. That expands further still when you take into account negative real (inflation-adjusted) rates as we saw with the TIPS example in the chart above. For a certain type of institutional investor – think pension funds, insurance companies and endowments with fixed spending plans – it simply is not workable to park the majority of your investable portfolios into ultra-safe bonds with negative purchasing power at best, negative income at worst.

These investors are not equity bulls – they are not piling into the stock market because they buy into all the silly babble about the “rocket ship economy” of certain political leaders’ fantasies. They are in the stock market because of TINA – There Is No Alternative. If a pension fund decides it has to increase its equity allocation, say from 35 to 40 percent, the result is a lot of new money coming into the market – much more than the collective volume of those over-caffeinated day trader bros with visions of V-shaped sugarplums dancing in their heads.

This is the world the Fed created. While the immediate benefits to quantitative easing and all those credit liquidity facilities are clear – forestalling a complete meltdown of financial markets – the longer-term risks are equally clear. As long as inflation stays low the Fed can keep pumping money into the system. If the gold bugs buying up precious metals are right about inflation, though, then this has the potential to be a collapsing house of cards. If there is one market view that you really, really want to be wrong, it is the high-inflation view. For what it’s worth we do not see compelling evidence of inflation surging much beyond the Fed’s two percent target in the next several years. But it would be wise not to rule it out completely.