Investors who went bullish on emerging markets equities in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 US presidential election must have looked daft to the conventional wisdom of the day. That wisdom (such as it was) saw non-US markets generally and EMs in particular being on the wrong side of the “reflation trade” – furious, price-busting growth in the US, a resurgent dollar and export-oriented economies left out in the cold by “America first.” EM investors who stuck to their guns got the last laugh. Since the beginning of 2017 the MSCI Emerging Markets index, a popular benchmark for the asset class, has appreciated more than 32 percent in local currency terms. The index has done even better in dollar terms (which is how a US-domiciled investor would tally her performance), largely because that anticipated dollar rally last year never happened, and EM currencies mostly rallied against the greenback.

Climbing the Wall of Worry

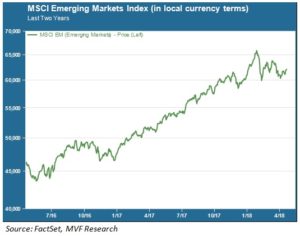

The first four months of 2018, of course, have produced a very different market for risk assets than the previous year. With all the clear and present fears of a trade war casting a pall on markets for the past two months it would be fair to say that emerging markets – prominent representative members of which are front and center in the trade war crosshairs – have had to climb a wall of worry. But for the most part climb they have, as the chart below illustrates.

EM equities took a big hit in early February, along with most other risk asset classes. But MSCI EM is still up by about 2.3 percent for the year to date (in price terms), which is better than either US large caps or most non-US developed markets. This, even though (a) the MSCI EM index is disproportionately represented by China and other Asia Pacific economies (more than 70 percent of the index’s total market cap) and (b) these very same Asian economies are central to the trade disputes making daily headlines. The relatively healthy recovery following the initial February pullback seems to offer persuasive evidence that investors do not ascribe a high probability to a scenario of all-out trade war. It also underscores some fundamental changes in global trade flows over the past decade. The old model of China and other emerging Asian economies largely dependent on exports of basic, low-value goods to the US is no longer valid. Trade flows are much more diversified, with an increasing percentage denoting trade among emerging economies themselves.

Additionally, Asia is now home to a larger number of world-beating companies domiciled in these countries, across a broad range of industry sectors including high value-add segments of research-driven technology like robotics, clean energy and quantum computing. Earnings prospects for these companies are strong, which keeps valuation levels from being excessive even after the strong growth of the past 16 months. In fact, regional forward price-earnings ratios in the low teens make for comparatively attractive value plays versus the current 17 times next twelve months (NTM) P/E ratio for the S&P 500.

A Rupee For Your Thoughts

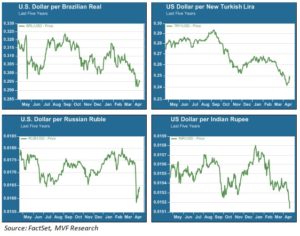

Investors still have a habit of treating emerging markets as a single asset class, despite the fact that differences between the key economies in this group are profound. A look at some recent trends in currency markets illustrates that what looks at first glance to be a dominant directional play is actually driven by very different variables. The chart below shows the performance of four currencies: the Brazilian real, Turkish lira, Russian ruble and Indian rupee.

To paraphrase Tolstoy, each of these dysfunctional currency trends is unhappy in its own special way. Brazil’s woes are a mix of politics and technicalities in the currency swaps market. Russia took a hit from renewed concern over sanctions in the wake of the recent US missile strikes in Syria. Volatility in the Turkish lira stems from local geopolitics as well as concern over a potential forthcoming rate hike. India’s economy has been in something of a funk of late, and recently it was added to the US’s list of currency manipulators (at the same time that, surprising to many observers, China was left off).

These all being local rather than asset class-wide stories, there may be little about which to be concerned for investors in a broad emerging markets equity play like the MSCI benchmark. It’s also worth noting that China’s currency is not suffering the same fate as the four shown above: the renminbi has gained ground this year and held steady throughout the recent trade war posturing. Fundamentally, the EM story would appear largely to remain sound. But historical trends have shown that investor perceptions of EM flows can turn on a dime. Those four individual currency stories illustrated above could morph into a single narrative that the asset class’s fortunes are due for a turn and it’s time to get out. Not what we would recommend at present – but it’s worth keeping an eye on how this plays out.