It was a great time to be in private equity, with record levels of new deals and a seemingly bottomless desire by investors for the speculative-grade debt raised by the private equity kingpins to fund their deals. Average yields of around 8.5 percent offered a tasty jolt of purchasing power in a world where headline inflation hovered just around two percent. Nor did the risks associated with debt rated below BBB- seem unduly out of line: the average spread of junk debt to benchmark US Treasuries was around three percent in the middle of the year, more or less in line with historical risk spreads.

That year was 2007, and the good times would not last for long. A year later, as the wheels came off the global financial system, yields on junk bonds spiked into the upper teens, with risk spreads to Treasuries jumping accordingly as panicked investors poured into the safest of asset classes. Anyone lured by the charms of junk bonds in that splendid summer of 2007 paid a heavy price.

Something’s Going to Give

Fast forward to the onset of the fourth quarter of 2021. Private equity volumes have already far surpassed their previous records of 2007, with over $800 billion pouring into more than 10,000 deals so far this year. Where private equity goes, speculative-grade debt follows as sure as the sun rises in the east. Just this week three of the biggest players in the private equity arena – Blackstone Group, Carlyle and Hellman & Friedman – announced a deal for a family-owned medical supply company called Medline that will raise $15 billion in new debt, most likely earning a rating of single-B. The total deal valuation of $34 billion (debt plus equity) makes Medline the biggest single private equity deal since that banner year of 2007.

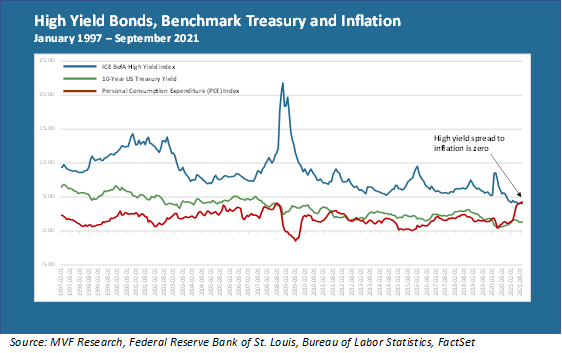

What are the bondholders going to get out of the deal? Consider the chart below.

Back in 2007, junk bond investors could at least satisfy themselves that they were getting a good deal relative to inflation. Today, for the first time in the history of this asset class, that purchasing power argument doesn’t hold. With inflation having risen over the past several months, the average yield on speculative debt – 4.03 percent according to the ICE BofA High Yield Index shown above – is lower than the latest Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) index of 4.3 percent released just this morning.

No Income, and Default Risk Too!

Something is clearly out of whack with this picture. Either inflation is going to drop very soon back to where it has been for most of the past ten-odd years, or current investors in junk bonds are in for some pain as yields rise to compensate for the loss of purchasing power. Which is it going to be?

Now, an observer of the above chart might note that the spread between speculative-grade debt and benchmark Treasuries has been quite stable ever since bond markets in general stabilized following the disruptions of March 2020 when the pandemic hit. Nominal Treasury yields, to be sure, are significantly below inflation at present. But institutions buy US government debt for all sorts of reasons only tangentially related to the earned yield – from foreign exchange reserves stockpiling by central banks to risk mitigation by portfolio managers. Historically, at least, investors have assumed the default risk on benchmark government debt to be zero (let’s hope that continues past the debt ceiling circus playing out now in Congress). The default risk on speculative debt, obviously, is not zero or anything close to it.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, the Fed stepped in to shore up credit markets by, among other things, committing to purchase junk bonds as a buyer of last resort. That explicit commitment ended after markets settled back down. Perhaps junk bond investors today think there is still an implicit commitment by the Fed to not let their holdings go south (there is not, but a person can dream). Perhaps the idea that zero purchasing power is an okay return for higher credit risk is the new normal. To our eyes, that chart says something else, which is that junk bonds are due for a significant repricing.