If you want to know what’s in store for stocks, pay attention to the bond market. That’s something we tell our clients repeatedly. Interest rates have an outsize effect on equity valuations. The shape of the Treasury yield curve contains all sorts of information about economic expectations. Credit risk spreads signal how much investors are demanding for taking on credits with a higher risk of default. In effect, the bond market is supposed to be the sober, thoughtful repository of market intelligence while the stock market’s day-to-day mood swings reflect a bundle of flighty emotions and mindless groupthink.

Dangerous Curves Ahead

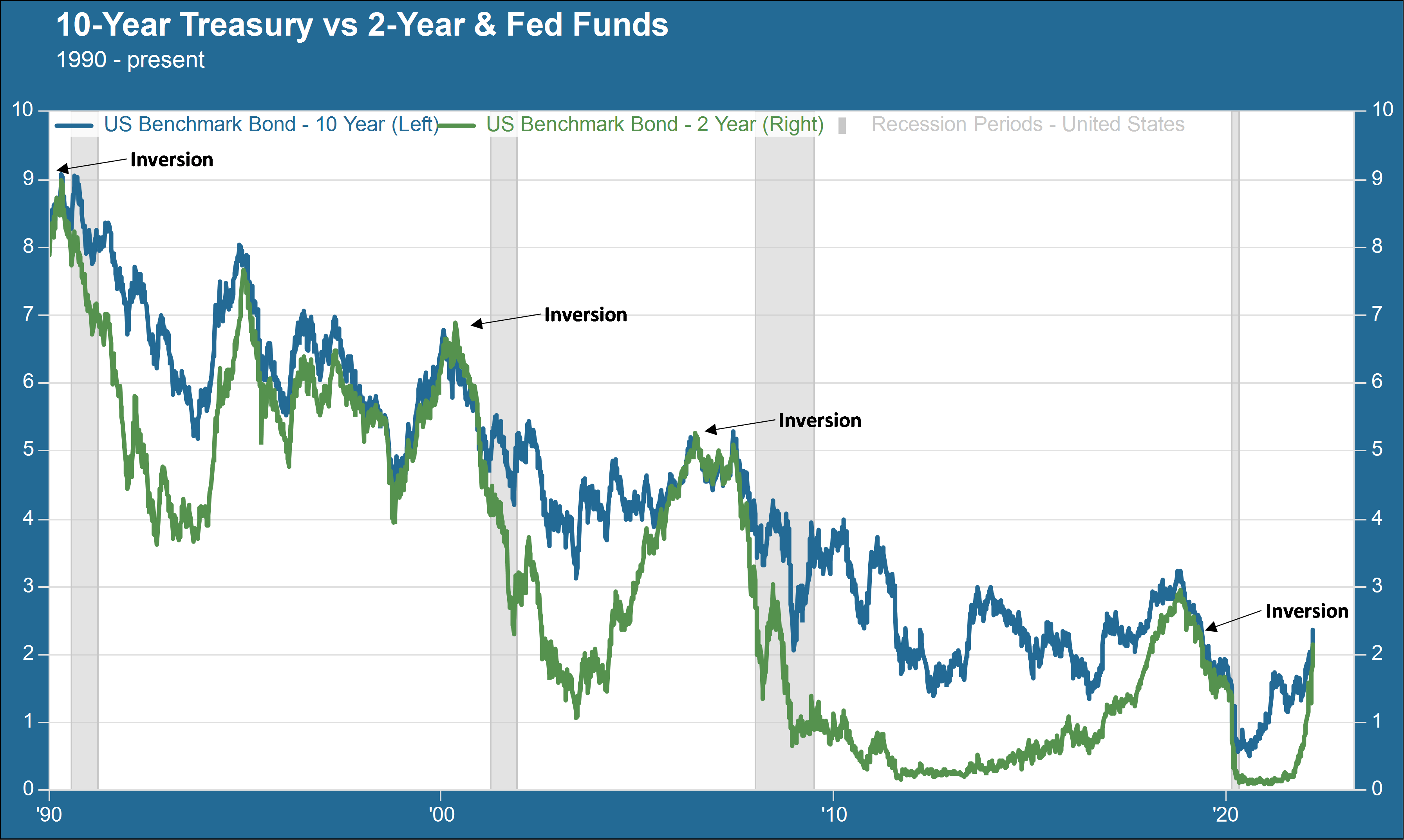

That’s how it’s supposed to work. But the bond market today seems to be sending out mixed messages. The Treasury yield curve has inverted slightly in the so-called “belly” – between the 5-year and 10-year Treasury notes. It is ever so close to doing the same in the wider expanse between the 2-year and 10-year maturities. A 2-10 inversion strikes fear into the heart of investors because of its historical prescience as a predictor of an approaching recession. The chart below shows this track record for the four recessions we have had since 1990.

A word about this chart is in order, though. The 2-10 curve inverted very briefly in the fall of 2019, and then we had a recession in 2020. But that recession had absolutely nothing to do with the economy of September 2019 or, for that matter, the economy of February 2020. The recession happened because we shut the economy down when the pandemic hit. Absent the pandemic, and given every other piece of data we have about the economy at the time, it seems highly unlikely that we would have gone into recession then. So the 2019 2-10 inversion would seem to need an asterisk, at best.

Nonetheless, the fact that the short end of the curve is rising while longer maturities stay put (or don’t rise by the same magnitude) would suggest that fears of an economic reversal are higher than they were several months ago. Last week, after the Federal Open Market Committee meeting, Fed chair Powell made the case that a series of methodical increases to the Fed funds rate would gradually bring down inflation while the unemployment rate would drop to 3.5 percent and stay there, with GDP growth continuing at a slightly above-trend cadence. The bond market, at least according to the flat yield curve, doesn’t seem to be fully on board with that assessment and thinks a harder landing may be in store.

Credit Risk Complacency

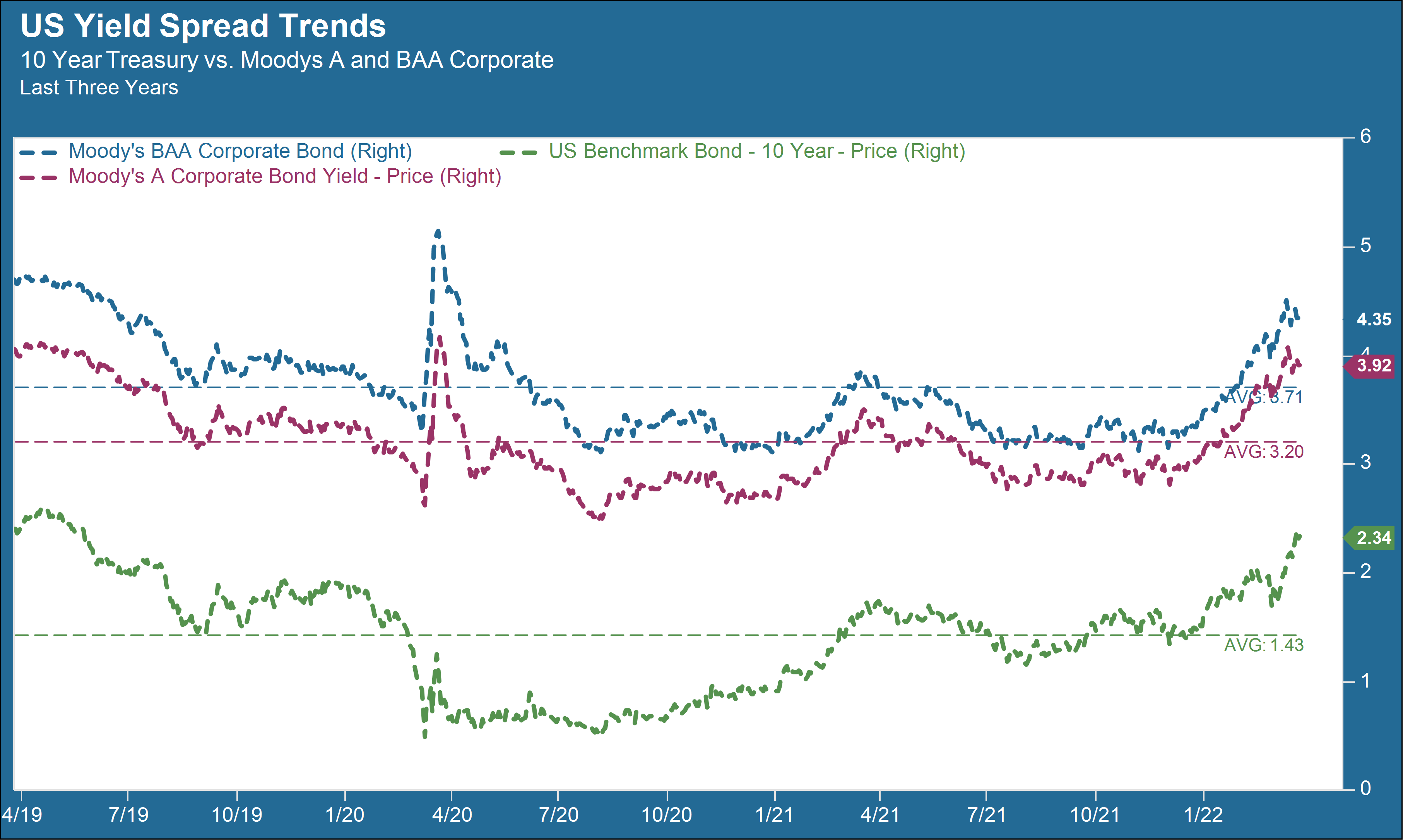

Then we come to another important bond market dynamic – credit risk spreads between benchmark Treasuries and corporate bonds. In particular, the spread between the 10-year Treasury and the riskiest investment grade corporates (Moody’s Baa) is just about two percent today. That is tighter than the three year average of about 2.3 percent, and comfortably within the normal range of the spread during economic growth periods, as shown in the chart below.

In other words, credit risk spreads are not telling us that we should be hunkering down for an oncoming recession. We would expect these spreads to widen in advance of a downturn, because the risk of default would be higher. Remember that the only way a bondholder loses money, assuming that she holds the bond to maturity, is for the company to default. Otherwise it’s a predictable stream of cash flows from timely interest and principal payments.

So which one of these messages is right? We have been on record for much of this year saying that the likelihood of a recession in the next twelve months is quite low, given current levels of consumer demand and a tight labor market. So in this sense we are more or less in line with the view Powell expressed at the FOMC press conference last week. That being said, we are not completely on board with the idea that inflation can come down from its current levels to the Fed’s two percent target without more pain than the soft landing of Powell’s worldview. We will be talking more in upcoming commentaries about some of the things going on in the world that may be beyond the Fed’s ability to fix with a benign, measured series of Fed funds rate hikes. Meanwhile, we think there might be a little truth in both those bond market signals, from the yield curve and from risk spreads.