On Thursday morning the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that first quarter GDP fell by 1.4 percent (on a quarter-to-quarter, annualized basis). The S&P 500 rose by 2.5 percent on the same day. That may sound odd, but in fact the market largely ignored the GDP story and focused instead on a crop of earnings reports from large tech companies that, on balance, came in better than expected. This tells us a couple things: first, how the market responds to macroeconomic data often has little to do with whether you might think the number in question is “good” or “bad” (we’ll get to this in regard to yesterday’s GDP number here below); second, what driving forces actually move stocks on any given day tends to be capricious and fortuitous; finally, and most importantly, correlation does not equal causation. Intraday stock market movements are less the necessary result of determinative Great Forces, and more like corks bobbing on the surface of the ocean, buffeted this way and that by the multiple natural phenomena of ever-shifting winds and tides and currents.

Below the Bad Headline

Nonetheless, the GDP number does merit some attention. Two consecutive quarters of negative growth may be all that’s required for a group of boffins at the National Bureau of Economic Research known as the Business Cycle Dating Committee to pronounce a recession. Since we at MV Financial have been maintaining for quite some time that we do not believe a recession is imminent, we feel we should discuss our own take on the Q1 number.

Going into Thursday morning’s release, the consensus expectation among economists was that the economy would grow by 1.1 percent from the previous quarter. The negative result relative to expectations came largely from two components. First, private business inventory growth was lackluster. This was more of a seasonal phenomenon than anything else: in the last quarter of 2021 businesses, fearing supply chain disruptions, stockpiled lots of inventory so as not to be caught short during the holiday season. That meant less need for restocking inventory in the first three months of this year.

Second, Americans imported a whole lot more than we exported during the quarter. This is actually a sign of economic strength relative to other parts of the world: consumers continued to buy foreign made goods even when those goods came with higher price tags on account of inflation. Other countries bought less stuff from us. From the standpoint of GDP math, negative net exports (i.e. when the total value of exports is less than the total value of imports) subtracts from growth.

The good news below the headline is that consumer spending and nonresidential fixed investment, which are arguably the two most important GDP categories for signifying economic health, were both positive and in line with recent trends. Consumer spending alone accounts for about 70 percent of total GDP, and grew 2.7 percent for the quarter. Taking all this into account, our often-expressed view that a near-term recession is not likely has not meaningfully changed.

The Persistence of Stagflation Fears

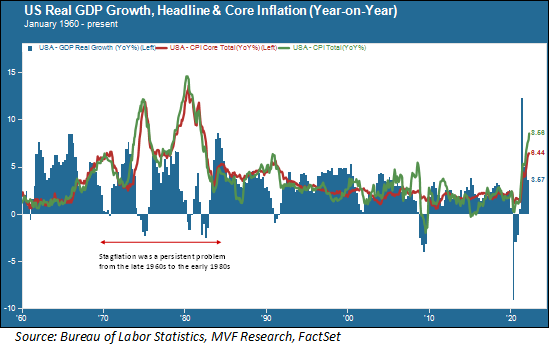

Our relatively benign view towards the likelihood of a near-term recession does not mean we are dismissive of the longer-term picture. The outcome nobody wants to see is anything that even rhymes with, let alone repeats, the stagflation of the 1970s. The combination of high consumer prices and low growth is a bad formula for most core equity and fixed income asset classes. So where are we on that basis today? The chart below shows real GDP growth along with headline and core (ex-food and energy) inflation going back to 1960.

In the above chart the stagflation period stands out, most notably the inability to bring inflation down below five percent for any sustained time until the draconian action on interest rates taken by the Volcker Fed in the early 1980s. The good news today is that we are not yet anywhere near the point where expectations about wages and prices are as embedded as they were throughout the 1970s. In a sense, the persistence of inflation today is due more to a string of bad luck than anything else. The ongoing Covid lockdown in China has prolonged supply chain problems, while the war in Ukraine has thrown a further wrench in energy and food prices (30 percent of the world’s total grain supply comes from Russia and Ukraine, and this year’s harvest in the latter country this year will be close to nonexistent).

So while we have not crossed the red-flag horizon for stagflation – and while the ex-food and energy numbers look like they are starting to stabilize – we cannot simply dismiss this outcome as a scenario. It will very much be in focus next week when the Fed meets and, if market expectations bear out, raises interest rates by another 0.5 percent. We will be very interested to hear Jay Powell’s views on current inflation and GDP trends when he speaks to reporters after the meeting. Much is riding on the Fed’s ability to make the right calls in an increasingly complex environment.