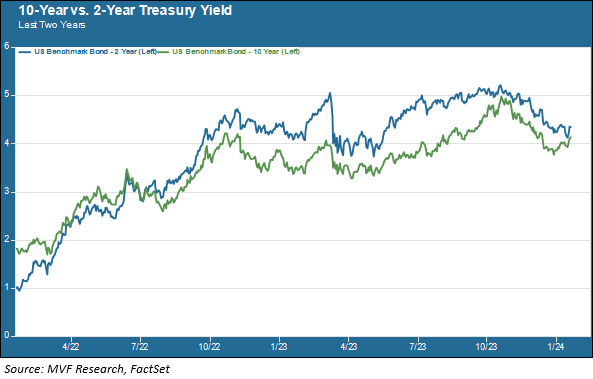

So close, and then so far. That was the story of the Treasury yield curve last October, when the 10-year yield briefly touched a decades-long high of five percent. For an ever so brief moment, it looked like the yield curve, stubbornly fixed in the inverted shape that in the past has been a reliable predictor of an approaching recession, might revert to normal. Then, a prominent hedge fund manager announced to the world his view that intermediate rates would not go any higher. Some more good news about inflation trickled in. Finally, the Fed came out of the December FOMC meeting with a rosier than anticipated view on rates, and the bond market had a jamboree. All of this knocked rates back, and the 10-year fell further than the 2-year. The inverted curve, it seemed, was here to stay.

Get ‘Em While They’re Hot

As has become the norm, the bond market took whatever the Fed said and doubled down. The December FOMC median best guess about the Fed funds rate in 2024 was three cuts for a total of 0.75 percent; the market immediately priced in six cuts for lopping 1.5 percent off the overnight rate. FOMO was back in full, with money managers and financial media talking heads insisting (for something like the 978th time in this monetary tightening cycle) that this was the “absolute last time” to lock in attractive yields for high-quality securities. Seasonality played a role, with a robust “Santa Claus rally” spilling over from stocks into the bond market (itself something of an oddity, since risk assets and safe havens normally move in opposite directions). Anyone who hadn’t seized the opportunity to get ten years’ worth of coupon clipping at five percent rushed to lock in their fortunes when the 10-year dropped below four percent.

Yet Another Repricing

Stop us if you’ve heard this one before. The bond market thinks there is a pony out back, runs outside and finds that the barn is still empty. January opened with something of a hangover after the fizzy good cheer of the December rally. Cooler heads were starting to actually think about why, exactly, the Fed would deliver six rate cuts in a year where, as far as we can see right now, there is a rapidly decreasing chance for a recession, inflation still has a possibly sticky “last mile” to go before it gets to the Fed’s two percent target, the jobs market is still healthy and – not an insignificant consideration for a politically cautious institutions like the Fed – it’s a particularly contentious election year. Rates have gone back up and, as the chart above shows, the 10-year yield is once again inching back towards the 2-year. The difference between the two yields is around 0.2 percent today; it was around 0.5 percent at the height of the December rally, and the spread has been as wide as one percent in the time since the curve first inverted in the summer of 2022.

RIP, Great Predictor of Recessions

So where does it go from here? Let’s revisit that observation we made a few paragraphs above: the presence of an inverted yield curve has long been viewed, correctly, as a harbinger of recession. A year ago that made sense, when the consensus opinion was that 2023 would bring a cyclical recession as a result of the most dramatic monetary tightening policy since the early 1980s. But the recession of 2023 never happened. It does not appear to be on the horizon as far ahead as we can see in 2024 as well. Unless conditions suddenly change (which is always a possibility), it would seem reasonable to assume that the 2-10 curve will at some point crawl back to its normal upward-sloping shape. While we think that incremental moves in this direction represent the most logical near-term path, we have seen enough of the bond market in the past year to not assume that logic has anything to do with it. We continue to gradually extend duration in our portfolios, believing that there is little more upside to be concentrated at the short end of the curve, but the best advice we can give as far as fixed income in general is concerned is to proceed with caution.