No, that headline is not referring to presidential debates. The first half of 2024 is drawing to a close today, and we have one more half year to go. Six months hence and we close the book on the fourth year of the Twenties (at least based on the evidence so far, we feel fairly confident in projecting that this century’s third decade will not come to be known by the history books as another Roaring Twenties – thoughts?). So what might the second half have in store for us?

No More Rate Cut Unicorns, But Maybe a September Pony

The first six months of the year were perhaps most notable for steadily weaning the bond market off its fantasies of multiple rate cuts. Recall that in December 2023, after a couple good inflation reports and some positive vibes from the Fed’s December FOMC meeting, the bond market was pricing in six rate cuts for 2024 (recall also, dear reader, our oft-repeated observation at the time that this viewpoint was on the far end of the delusional spectrum). It took three months of higher than expected Consumer Price Index reports, from January through March, to bring the bond market back to Earth One and the realization that doubling down on the Fed’s own best guess about rates (three rate cuts) was just a tad inadvisable. In fact, those sticky inflation reports forced the Fed to reevaluate its own assumptions. Now, two and a half years after monetary tightening began in March 2022, the Fed and the bond market are finally more or less aligned – if not happily than at least resignedly – one the more likely outcome of one rate cut before the year ends.

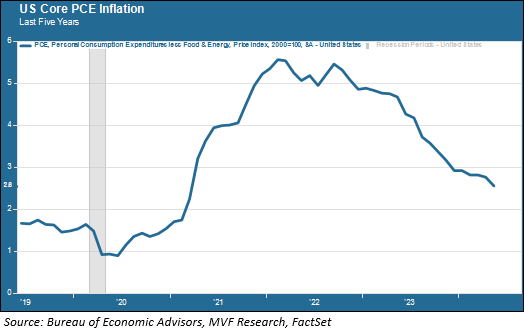

The pony for the markets is that, based on the latest inflation read this morning, that cut may come by September rather than December. The Personal Consumption Expenditure index less food and energy (core PCE), which is the Fed’s preferred inflation metric, rose by just 0.08 percent in May for a year-on-year gain of 2.6 percent – the lowest level since March 2021.

The month-on-month number is what we have been focusing on for clues as to when the Fed might feel comfortable pushing the button. Anything less than a 0.3 percent monthly increase is good news, and the May gain of 0.08 percent follows April’s 0.26 percent rise. If we get another two months of a sub-0.3 percent core PCE reading in July and August, all else being equal we would think the odds are better than not for a September cut. That in turn could set up a nice tailwind to get through the often bumpy early weeks of the fourth quarter into the holiday season and a strong finish.

How Much More for AI?

The other big trend in the first half, of course, was the continued outperformance of the AI narrative (which we talked about in some detail in our commentary last week). That tailwind turned into a headwind of sorts over the past few days, though we would imagine more from investors trimming positions and taking some money off the table than from any fundamental change in the dynamics of the sector. The performance bar was set very high for AI-centric companies like Micron, which reported strong earnings earlier this week but took a beating anyway as the market determined that “strong” isn’t the same as “super-awesome barnstormingly ga-ga strong” with regard to the company’s forward revenue guidance. Whatever. We are seeing genuine AI use cases showing up in an increasing number of earnings reports across a wide spectrum of industry sectors, and lots of related capital expenditure outlays, which suggests that this narrative has some ways to go before it burns itself out.

Landing the Plane, Ever So Softly

As for the general economy, nothing we can see in recent data releases suggests a change to the assumption for a slowdown, with growth remaining modestly positive. The latest consensus from the economist crowd at Blue Chip Economic Indicators has a median forecast of 2.0 percent real GDP growth for the second quarter, the report for which will come out in late July. Recent data points from the labor market to durable goods and retail sales all point to a moderation in the hitherto torrid pace of consumer spending, with little to suggest that the slowdown will turn into a recession. And thus will the storied predictive powers of the inverted Treasury yield curve be forever put to rest. Sic transit gloria mundi.

In summary, we do not see much right now that would cause a major rethinking of where we are positioned in our portfolios. That is not to suggest that it will be a smooth ride for the next six months, or free of surprises. We imagine there will be a few of those lying in wait. But in the meantime we will take it one week at a time.