Picasso’s 1932 painting “Girl Before a Mirror” is, like most of the artist’s work, open to wide and contentious speculation about “what it all means,” and in that sense it bears a likeness to today’s jobs report. Does the weak headline payroll number suggest an economy confronting its own dark mortality, like (perhaps) the girl in the painting? Put three art majors in front of the painting and you’re likely to get five opinions. The same appears to be true for economists as they look at the various discordant bits of the BLS report and try to piece it all together.

You have that bad payroll number (and downward revisions to previous months) alongside the best unemployment rate figure in nine years. There are meaningful improvements in the number of long-term unemployed, but the labor participation rate also fell for the second month in a row. Wages continue to make steady gains and remain ahead of both core and headline inflation – but shouldn’t wage growth be even higher at this stage of a recovery? The payroll numbers were impacted by a labor strike at Verizon, but that was not a big enough impact to offset the actual number falling more than 100,000 jobs short of consensus expectations. What is this disjointed picture trying to tell us? Or are we, like so many art critics, simply overthinking the importance and meaning of one single report?

A Bit More Pain with the Gains

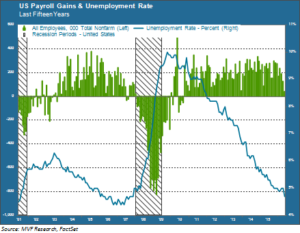

What we can say for sure is that, almost halfway through 2016, the pace of payroll gains is weaker than it was for the past couple years. It was the rare month in 2014 and 2015 that failed to serve up at least 200,000 new jobs. When the number did fall short, stock indexes either rallied (Fed’s not going to raise rates!) or plunged (economy’s getting worse!) depending on what side of the bed Mr. Market woke up that morning. The average for the past three months, including the downward revisions to April and March, is 116,000. So the benchmark has come down. Even so, though, the current environment for jobs creation looks strong compared to the previous recovery in 2003-07, as shown in the chart below.

Not only is the current recovery the longest uninterrupted streak of positive jobs creation since the BLS started keeping records but, as shown in the chart above, the number of months with 200,000 jobs or more is higher and more consistent than it was in 2003-07. It may be natural, after such a long winning streak, for the pace to slacken off a bit. If the economy can manage to sustain a pace of more than 100,000 monthly payroll gains and continued steady wage improvement for at least another year or more, that would likely count as a win. For now, anyway, signs of a recession do not seem to be anywhere on the horizon.

Yes, But…

However one chooses to interpret the payroll number, the labor participation rate leaves less room for creative opinionating. After showing some long-awaited signs of life in the first quarter of the year, the participation rate has fallen back down to 62.6 percent, just 0.2 percent above the decades-long low reached in September last year. Given that a lower participation rate means fewer people out actually looking for work, this trend also throws a bit of a wet blanket on that headline 4.7 percent unemployment rate. Remember that economic growth only happens when more people work or when more stuff gets produced for each hour of labor. With both the labor participation rate and the productivity rate in what appears to be a secular stagnation, the long-term growth question remains a mystery.

Of course, the conversation today and in the run-up to the next FOMC meeting in just 11 days will focus on what today’s numbers mean for interest rates. Our guess is that they mean very little. The Fed is likely more focused on the latest Brexit poll numbers than anything else as far as June is concerned, given their possible effect (however short term) on the all-important asset markets. There will then be a whole new batch of price, growth and jobs data to consider before July rolls around. Maybe it really is best to think of today’s jobs report as a Picasso painting – you can interpret it however you want, and your interpretation has no practical consequences in the real world.