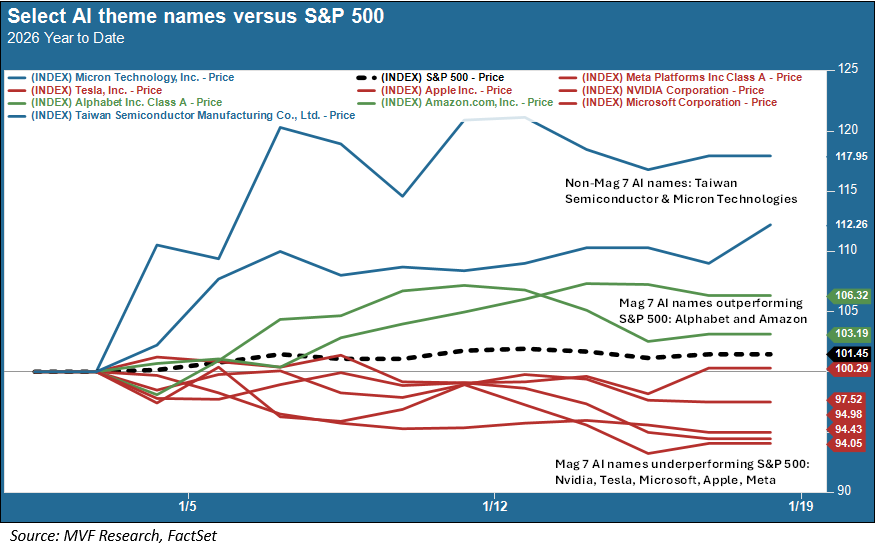

Since we are now sixteen days into Year 2026 of the Common Era, it is once again time for everyone in the financial field to make bold pronouncements about the Great Rotation that is to January what the Great Pumpkin of Peanuts fame is to October (i.e., the wild imagining of an impressionable mind). It’s true that small cap and value stocks have done comparatively well in this year’s early days. And as of this morning five of the fabled “Magnificent Seven” stocks that for the past three years have served as an easy market shorthand for “AI leaders” are trailing the S&P 500. But the way we see it, this is less about the eclipse of the AI narrative, which shows no signs of going away as a core component of US economic growth, than it is about the AI story getting more complicated, with more careful parsing of where different companies actually stack up in the narrative. We’ll introduce two names in the chart below that are not part of the Mag Seven but are very much at the center of all things AI: Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC) and Micron Technologies.

What’s In a Name

In the chart above we see outsize gains for the year so far by Micron and TSMC, up 18 percent and 12 percent respectively. Among the Mag 7 only Alphabet and Amazon are ahead of the index while Nvidia is just slightly behind and the other four (Tesla, Microsoft, Apple and Meta) trail by a wider margin. This week TSMC, which essentially manufactures all the chips that other companies design, reported another quarter of blowout earnings, growing revenue by more than 20 percent, expanding gross and operating profit margins, and raising its forward guidance by more than the consensus of sell-side analysts had expected (and they had expected a lot – the performance bar for TSMC was high). In terms of the potential impact on overall economic growth, TSMC’s capital expenditure forecast was also raised to $52-56 billion for this year alone, with more to follow. Translation: the AI infrastructure spending binge that has been the central economic story for the past three years is not slowing down. For this single reason, let alone other factors like consumer spending or net exports, we believe it remains unlikely that we will see a recession in the US this year.

One big part of that infrastructure spending binge will be on memory, in the form of DRAM chips, and that is where Micron Technologies comes into the story. Micron has been around for a very long time, and its core competency for all this time has been the comparatively dull memory segment of the chip market. It turns out, though, that the memory capabilities of Micron’s DRAM chips are essential to AI model development, and currently demand is outpacing supply. Micron is investing heavily to meet that increased demand – hence, yes, more spending that will translate into the GDP growth equation.

Tell Me Your Story

We focused on these two companies (there are others) because they reflect a general sharpening in the AI story that, we think, will lead to more dispersion among the performance of stocks in this space, rather than the simplistic “buy Mag Seven” story of yesteryear. Tesla, Apple and Meta are the names we think could be on the other end of this dispersion (though any one or all of them could perform well for other reasons – none of them are AI pure plays in any sense). As for Nvidia, which has been the big name in this space ever since ChatGPT mania took off in early 2023, it continues to maintain a solid competitive advantage in supplying the leading edge of graphic processing unit (GPU) chips to AI developers. But competition from China, while not fully formed today, will be a competitive threat the company must take into account as it charts the next phase of its strategy.

Back to the issue we raised back at the beginning of this piece, about the purported Great Rotation from the things that have done well recently to the undervalued corners of the market among value and small cap names. Will this happen, or will it fizzle out as these things often do? We don’t know, nor are we inclined to shuffle around a lot and run up big capital gains in order to find out. We are less interested in momentum-driven rotations and more interested in having a better understanding of the landscape in that part of the market situated at the center of economic growth. For now, at least, that remains the dynamic and constantly changing AI space.