Well, that was quite a week. Not often do we see the human frailties behind the bland policy statements, but raw emotions were on full display as European policymakers scraped together a 12th-hour deal to – for now – keep Greece in the Eurozone. By all accounts Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras was raked over the coals as representatives of the creditors vented in turn over the chronic misbehavior of the Greeks. But the real ire showed itself not to be that of the North-South variety – old news – but the clear philosophical divisions at the core of Project Europe. We don’t imagine we have seen the last of the endless bailout requests coming from Athens – not by a long shot. But the more interesting story – and potentially the one more consequential for asset markets in the coming months – is whether the Eurozone can regain the stature and credibility it lost over the past weekend. It has its work cut out.

The Talented Mr. Tsipras

The creditor side’s loss of the moral high ground can be seen in the respective public opinion fates of the two principal faces of the drama this week, Greek PM Tsipras and German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Recall that, just one week earlier, the Greek citizenry had delivered a resounding “No” to the austerity measures contained in the most recent proposal, which “No” extended to any deal without explicit conditions for debt relief. The deal to which a bleary-eyed Tsipras agreed in the early hours of Monday morning (just in time for the stock markets!) contained even more severe measures to raise taxes, slash pensions and even make Greek bakers compete with each other with fewer government protections. It included no assurances of debt relief. And it insisted on a hugely accelerated timetable for implementation of these measures as a requirement for proceeding with the financial relief needed to reopen the cash-starved Greek banks.

And yet, Mr. Tsipras not only managed to shepherd all these tough measures through Parliament with a 229-64 margin, but also won the backing of 70% of the population for his handling of the negotiations. Say what you will about the seemingly inept performance of the Tsipras team during the negotiations – the man does have his finger on the pulse of his country. Even Germany’s leading periodicals grudgingly acknowledged that Mr. Tsipras is likely to be showing up as Greece’s key man at the negotiating tables for some time to come.

For Every Borrower, a Lender

The week’s PR consensus was far less kind to German Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose name showed up repeatedly next to phrases like “return to old nationalist grudges” and “darkest moments of the last century” – not phrases with which any German politician would wish to be associated. There was broad agreement that the final terms of the deal went above and beyond what could be considered reasonable austerity measures, and reflected instead misplaced moralism and vindictiveness on the creditors’ part. Ironically, this managed to do what five years of negotiations had not; to bring into the mainstream the argument that Greece alone does not bear responsibility for where we are today – that for every borrower there is a lender, and that a large number of those lenders reside in Frankfurt. Unfortunately, this reality shines a cold light on the very structure of the single currency union which, in hindsight, seemed fated to bring these borrowers and lenders together.

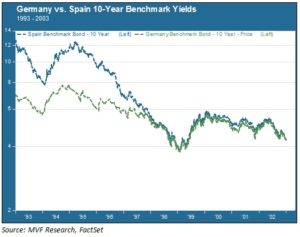

The single currency zone envisioned by the architects of Project Europe was never the ultimate objective itself, but rather it was intended to be a natural reflection of political union – a unified Europe that had successfully overcome the national identities that too often in the past had resulted in bloodshed. It was a stirring vision indeed, but not a realistic one. For all the ways in which it has converged, Europe remains a continent of distinct languages, cultures and – yes – approaches to economics. Greece, to give one example, will never share a common view of inflation with Germany, a country still haunted to this day by the extreme hyperinflation of 1922-23. A united Europe with a united currency was a laudable vision. But when the Eurozone was launched in 1999 it imposed a unity that was well before its time. Consider the following chart, which shows the benchmark 10-year sovereign bonds for Germany and Spain from 1993 – 2003: the years leading up to and after the euro’s launch:

Historically Spanish debt traded at a sizable spread to Germany’s issues, reflecting quite naturally the different compositions of the two economies and the relative risks inherent therein. As the chart shows, the spread converged to zero with the introduction of the single currency. As for Spain, so for all other so-called peripheral economies including, yes, Greece. Who wouldn’t go out to tap the debt markets under these conditions?

On the other side of the equation, Germany’s economic choices in the years following the costly reunification between East and West Germany were more focused on restoring national fiscal and trade balances than on anything elsewhere on the Continent – again reflecting a deep-seated national loathing of deficits and inflation. The result was a growing current account surplus that – in the absence of sufficient domestic demand – found a natural destination in loans to Greece, Spain, Portugal et al. It was a natural road from there to here.

Beware the Spirit of 1919

John Maynard Keynes was part of the British delegation to the Versailles peace conference in 1919 that dealt with reparations from the destruction of the First World War. His dismay at the self-serving policy positions of the national negotiating parties led to his publishing “The Economic Consequences of the Peace” – which turned out to be an alarmingly cautionary tale. Now – today is not 1919, and our policymaking institutions are, for all their faults, superior to those that repeatedly botched the opportunities of the 1920s. But Europe is in a fragile position in the wake of this week’s events, with divisions and resentments laid bare. If the single currency region is to succeed – and we believe it is in the interests of the global economy that it does succeed – we will need to see more effort applied to fixing the parts of the system presenting the biggest barriers to real unity. The fractured financial system should be the first project on this list. A system of fiscal transfers between Eurozone states could prove a better safeguard against future defaults than the current flawed system of patchwork bailouts. If Greece can be a part of this system, then all the better. If not, then it is now time to move on.