This has been a week of extreme nerves and emotions in our country, a week in which we have seen manifest evidence of both our darkest demons and our better angels playing out on the national stage. Our hearts go out to the family of George Floyd and to all who are victims of injustice everywhere. They remind us that we have to work ever harder to cherish and protect the dignity and the humanity that is common to all of us. We believe (albeit sometimes with difficulty) in the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. repeated so many times by former President Obama, that the arc of history bends towards justice.

The Non-Political Nature of Markets

Since this a commentary about markets and the economy, we turn our focus this week to another period of domestic unrest in our modern American history, and the lessons it might offer. 1968 was a year when it often appeared that the center was not going to hold: a year of two headline assassinations (Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy), riots and chaos at the Democratic National Convention and other sporadic conflagrations. This came on the heels of 1967, which witnessed debilitating riots in Newark, New Jersey and Detroit, Michigan as a confluence of civil rights issues and opposition to the Vietnam War sparked a rapidly increasing conflagration.

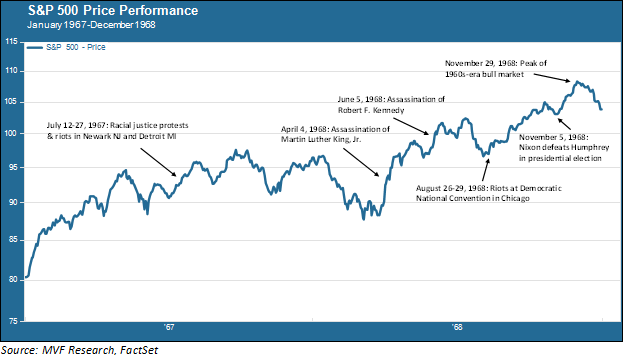

Not that you would know that anything was wrong by looking at the stock market – sound familiar? It should. Markets have long demonstrated the tendency to ignore both domestic unrest and geographical flashpoints. In the chart below we see a timeline of some of these prominent events during that two year period along with the generally upbeat tone of the S&P 500. The blue chip equity index gained about 33 percent, cumulatively, over this time, blithely rallying through some of the era’s worst moments.

Society, Politics and the Economy

Looking at the carefree ascent of the stock market in 1968, it is easier to understand why markets in the current environment are likewise sanguine. In addition to the increasing domestic unrest in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, we continue to see a festering slow-burn increase in hostility between the US and China – the world’s two largest economies. Plus, of course, the ongoing edginess related to all the uncertainties that still surround the coronavirus pandemic. But the market remains fixated on the belief that the worst of the pandemic is behind us and that the economy is on the cusp of roaring back to life. A much better than expected jobs report today adds fuel to the optimists (though, as valuations on the S&P 500 fly Icarus-like towards the scorching sunny realms of the 2000 tech bubble, they might want to remember how that ended).

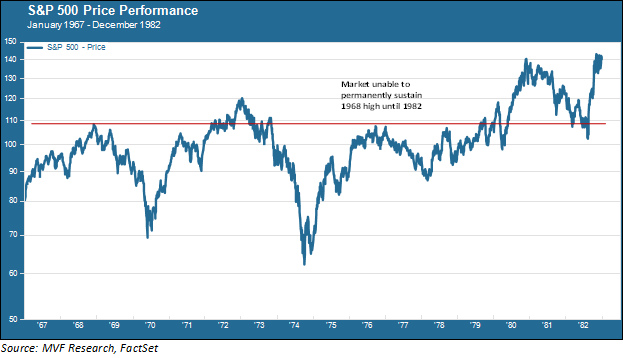

In hindsight, we know that 1968 was a last gasp of optimism for a bull market that had run through most of the 1960s. It was the zenith of American power worldwide in the framework of the Bretton Woods agreement that set the economic agenda for the postwar era. But by 1968 the institutions and practices that made this all possible were fraying. The social unrest of the time was not somehow separate from the rampant inflation and weakening global power of US corporations. While investment markets largely ignore short-term social unrest, in the long run they are affected by structural socio-economic breakdowns. As the chart below illustrates, the stock market was not able to sustain a level above that 1968 high for fully 14 years, as the economy stagnated and slowly groped its way towards a new paradigm.

The Present Age and Its Discontents

The causes of any specific outpouring of discontent are typically local and contextual, as has been the case with the protests in our cities and towns over the past couple weeks. But they are not divorced from the structural problems intertwined with the country’s economic progress since the financial collapse in 2008. In many ways that collapse underscored the fatigue and fragility of the dominant institutions and practices at play since the early 1980s. The decade that followed was a weak and very uneven cadence of economic growth held together by the continued support of the Federal Reserve. Just as Bretton Woods had largely run its course by the late 1960, so the neoliberal “Washington Consensus” of unregulated globalization and its corporate-profits-above-all-mindset has lost its luster.

We don’t tend to make these connections directly – between the catalysts of any given burst of domestic unrest or geopolitical dust-up and the larger structural issues at play. But the connection is there. Meanwhile the economy continues to grope through the fog for a new paradigm, and we all try to imagine – with very incomplete information – what that will be. Ultimately, something other than mere nursemaiding by the central bank will be necessary.

Please be well and be safe and know that we stand with you in these trying times.