The US stock market is setting up to fall for a fourth straight week, the first time this will have happened since early fall 2020. Amid the dour talk on financial news programs, though, all is not entirely negative. We got a trifecta of information this week from the Fed, from the latest economic growth numbers and from a new inflation release. There was also a batch of important corporate earnings reports, including from tech giants Apple and Microsoft. What they all seem to clarify (with a few important caveats) is that the current economic cycle is going to look different from the last one in some important ways.

Where in the Cycle Are We?

There has been some manner of debate among economists as to whether we can even talk about being in a “new cycle” different from the one that ran from the end of the financial crisis in early 2009 to the pandemic in March 2020. That cycle was punctuated by the very briefest of recessions, lasting all of two months from March to May and then washed away by the tsunami of new money from both fiscal relief and easy monetary policy. So we had eleven years of growth (already the longest continuous recovery on record) punctuated by a brief killing of the switch with the lockdown, and then back to growth.

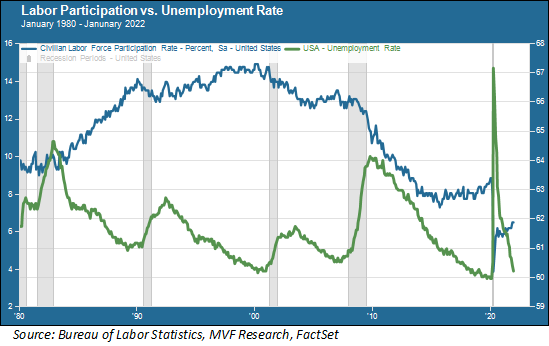

But what the recession lacked in duration it certainly made up for in depth, with record levels of decline in both real GDP and in jobs. That adds a magnitude of complexity to trying to figure out where in the cycle we are now. Consider the jobs market. The chart below shows the labor market trend over four economic cycles (prior to the pandemic) going back to 1980.

The green trend line here shows the unemployment rate. You can see that this rate falls slowly over the course of the growth cycle and then rises quickly early in a recession (the gray vertical bars represent US recessionary periods). In 2020, after reaching its lowest level since 1969, the unemployment rate shoots up to over 14 percent at the beginning of the lockdown – the highest rate since the Great Depression – and then within the space of just one and a half years falls back almost to that February 2020 low. Looking at that chart, one could almost make the case for just ignoring the distortions of the lockdown, and saying that we are just in the same growth cycle that began in 2009, just a little closer to the end.

More Growth, Less Fed

What we got from this week’s information feed, though, was some reasonably convincing evidence against that assumption. Let’s start with the Fed. First of all, let’s remember that much of that long growth period of the 2010s was driven by the energetic injection of money into the economy via the Fed’s series of quantitative easing programs and the maintaining of historically low interest rates. Growth in this environment was also below historical trends, and so was inflation. Because inflation was so persistently low, the Fed could pivot back to an easy money stance when asset market disruptions made it nervous – this happened at the beginning of 2016 and again at the beginning of 2019.

There was a different Fed on display at the press conference following the FOMC meeting this past Wednesday. Fed chair Powell made it clear time and again that fighting inflation was the number one task at hand, that labor market conditions suggested we were more or less already at full employment, and that stock market disruptions (this was a direct question posed by a couple reporters in attendance) would not be diverting attention from the challenges in the real economy – yes, Powell did use that particular phrase to contrast the world of goods and people with that of meme stocks and bitcoin.

The day after the FOMC press conference came news of the highest rate of annual economic growth in a couple generations, surpassing the already-elevated expectations. That rate of growth is very unlikely to continue into 2022, but it is not unreasonable to expect that the trend will resume to higher levels than was the norm in the 2009-20 period. Consumer demand remains high. Consumer confidence was another macro data point that came in this week, and it was also higher than the consensus forecast. The outlook for corporate earnings is in the high-single digit to low-double digit range.

More Inflation, But Manageable

Finally the Personal Consumption Expenditures index, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, reported headline inflation of 5.8 percent last month (year-on-year) and 4.9 percent core (ex food and energy) inflation, both in line with forecasts. There is some evidence that supply chain hiccups are starting to settle down. There is, so far, less evidence that available jobs are going to start filling up any quicker than they have been. If you go back to that chart above you will see that the labor force participation rate (the blue trend line), while up a bit from its pandemic low, is well below where it was before. There are reasons for this that have to do both with current pandemic-related conditions and with more structural demographic changes. The net effect is that the labor market is likely to be one factor that continues to exert upward pressure on inflation. Rather than that gradual decline towards full employment seen in previous cycles, this time the unemployment rate could just move along sideways in the low-three percent range for a good part of the remainder of this cycle.

And how long will this cycle continue? Anyone who says they know the answer to this is kidding themselves (and you). But for the time being, organic growth with less Fed intervention and higher but still manageable inflation is far from the worst scenario we could envision. It’s a good time to tune out the noise of intraday volatility and stay focused on the higher-quality segments of the market we think have a better chance at doing well.