We are heading into that final, frenetic stretch of the year. Tomorrow most of us will put aside the travails and tribulations of markets and the economy and turn our attention to the culinary delights and company of loved ones at the Thanksgiving table. Then comes Black Friday and the high-octane sport of holiday shopping. As the year races to a close, the financial industry will furiously churn out its annual tsunami of predictions for how markets will perform in 2023, most of which will likely lose their predictive value by, oh, March of next year.

However, there is one thing you are likely to hear a lot of in the coming weeks that we think does carry merit: much of the big thinking about portfolio composition in the year ahead is going to focus on fixed income. No longer just the quiet quadrant where you park “safety money,” bonds are now offering the kind of potential value not seen since long before phrases like “quantitative easing” and ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) entered the financial lexicon. At the same time, the shape of maturities and yields in the Treasury market is signaling danger ahead. Making sense of the opportunities and attendant risks in the bond market is a clear and present priority.

What a Difference a Year Makes

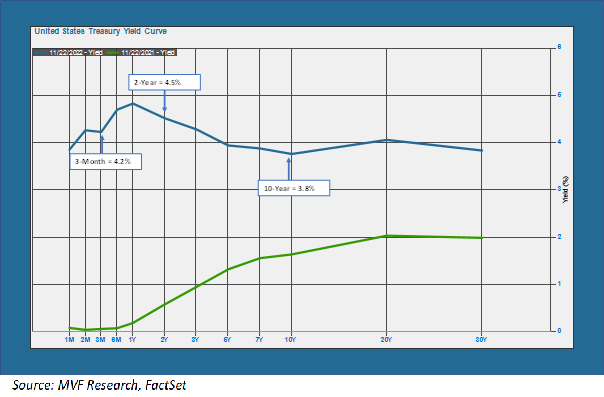

The Treasury yield curve, shown in the chart below, neatly summarizes the opportunities and the risks alike.

Let’s start with the opportunities. A year ago, every Treasury maturity up to one year was at or very close to zero (the green trendline in the chart). Today, an investment in a 3-month T-bill gets you a 4.2 percent yield, while you can park funds in a 2-year Treasury note for an even better 4.5 percent coupon. Now that’s a nominal yield, of course, and inflation is still running north of mid-single digits. But if you buy into those “dot-plot” prognostications of the Federal Open Market Committee which have inflation back down to 2 percent by 2025 (2.3 percent in 2024 according to the most recent Summary Economic Projections from the FOMC meeting back in September) then maybe locking in that 3.8 percent yield on the 10-year note looks attractive. There are alternative ways to obtain value, in other words, for quality-seeking portfolios which have been yield-starved for a very long time.

Curvy Weirdness

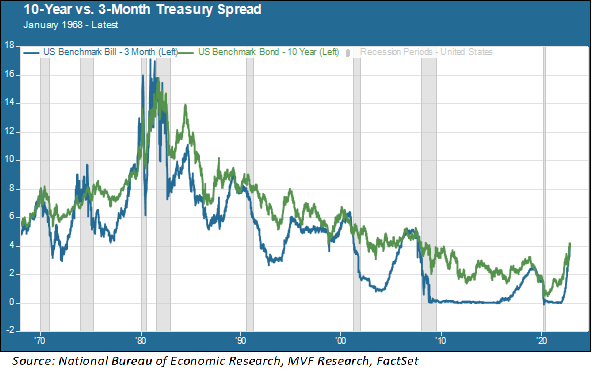

That same yield curve shows the potential risks ahead. As you can see, the curve is inverted all the way from the shortest maturity (3.85 percent for the 1-month bill) to the longest (3.83 percent for the 30-year bond). That rings alarm bells, because an inverted yield curve has historically been arguably the most reliable indicator of an approaching recession. The chart below plots the 3-month T-bill against the 10-year note going back to 1968, showing that ahead of every subsequent recession (eight total) the short-term yield moved up and inverted against the 10-year yield.

The current consensus among economists is that there is about a 65 percent chance for a recession sometime in the first half of 2023 (it’s also fair to trot out the old saw that economists have predicted ten of the last eight recessions, nevertheless here we are). The yield curve says we should expect one sooner or later (the predictive power of the curve inversion does not extend to any kind of precision in the timing, it should be noted). So what could that mean for the kind of assets you do and do not want to put into your fixed income portfolio in the year ahead?

One of the key assumptions associated with a near-term recession is that risk spreads would widen from where they are today. Currently the spread between intermediate Treasuries and other asset classes like lower-quality investment grade bonds (e.g. with BBB/Baa credit ratings) is pretty close to its three-year average. Those spreads would likely widen ahead of a recession. Remember that when yields rise, bond prices fall, and they would thus fall faster for riskier asset classes relative to Treasuries and other higher quality assets.

Does that mean you should stay away from anything other than the highest quality assets? Not necessarily. Remember that if you invest in a bond and hold it to term, the key risk that could separate you from your expected cash flow stream is a default by the issuer. In the world of high yield bonds, particularly the lower tiers of that asset class, this is a meaningful risk during an economic downturn. However, if we have a relatively mild recession – which at this point seems to be a likelier outcome than a protracted and deeply painful event – then a diversified pool of investment-grade bonds with a mix of credit ratings from AAA to BBB can be worth taking on a bit of extra credit risk for the higher yields they offer. The average yield on Moody’s A-rated corporates is around 5.45 percent and for Baa-rated issues it is 5.91 percent. For income-seeking portfolios that is at least worth some consideration.

These and plenty of other questions will be occupying our minds in the weeks ahead. For now, though, we wish each and every one of you a very happy, healthy, restful and delicious Thanksgiving.