There is something almost symmetrical about it all. On December 19 last year the Federal Reserve delivered a hawkish monetary policy statement that sent the stock market into a tailspin. Two days later the US government shut down. Fast forward to January 25 of this year. The US government reopened amid generally upbeat sentiment in asset markets. Several days later, the Fed surprised traders with a decidedly dovish policy statement hinting at a pause, not only in further interest rate hikes but in winding down the central bank’s balance sheet of bonds purchased during the quantitative easing (QE) era of 2008-14. Stocks surged in the aftermath of that announcement and closed out a January for the record books. Hallelujah, exclaims Mr. Market. The Fed put is back and better than ever!

What Exactly Changed?

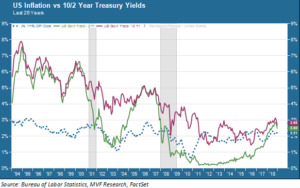

The January Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) statement was not just a tweak or two away from the December communiqué – no, this was closer to a full-blown U-turn. As much as investors thrilled to the news that the Fed was solidly back in their corner to privatize gains and socialize losses, there was quite a bit of head-scratching over what exactly was so momentously different in the world over this 30 day interval. The FOMC press release seemed to say little about changes in economic growth prospects, with a strong labor market and moderate inflation paving the way for a sustained run of this growth cycle. True, it chose the world “solid” to characterize growth, which may be a slight demotion from “strong” as the adjective of choice in December. And yes, muted inflation affords some leeway to adjust policy if actual data were to come to light. But real (inflation-adjusted) rates are nowhere near recent historical norms, as illustrated in the chart below.

“Muted inflation” is the Fed’s term to describe the current level – but is it really “muted?” The chart above shows the Consumer Price Index (the blue dotted line) to be squarely within a normal range consistent with growth market cycles in the late 1990s and the mid-2000s. Yet in both of those cycles real rates were much higher, as is clear from the gap between nominal 2-year and 10-year yields (green and crimson respectively) and the CPI. Is the Fed worried that real rates at those levels today would be harmful? If so, there must be some element of fragility to the current economy that wasn’t there before.

Oh, Right. That.

Or, maybe that’s not it at all, as the FOMC press release sort of gives away in the next sentence. “In light of global economic and financial developments…” Aha, there it is, the language of the 2016 Yellen put reborn as the 2019 Powell put. What, pray tell, could those “financial developments” possibly be? A stock market pullback, blame for which was almost entirely laid at the feet of those two FOMC press releases last September and December? Once again, monetary policy appears to be based principally on ensuring that market forces not be given free enough latitude to inflict actual damage on investment returns.

And maybe that’s fine – perhaps the pace of growth will continue to be slow enough to allow the Fed to ease off the monetary brakes without any collateral damage. If that turns out not to be the case, though, then we foresee some communication challenges ahead. The data continue to suggest the growth cycle has a way to go before petering out. Today’s jobs report was once again robust, with year-on-year wage growth solidifying a trend in the area of 3.2 percent year-on-year. Unfortunately we won’t know about Q4 2018 GDP for some time, as the Bureau of Economic Analysis was impacted by the government shutdown and does not yet have a date for when its analysis will be ready for release.

March is probably safe – the likelihood of a rate hike then is now close to zero. But if Powell has to go back to the market sometime later in the year and ask investors to get their heads around another rate hike – a U-turn from the U-turn, in effect – that would likely be problematic. This Fed still has a learning curve to master when it comes to clarity of communication.