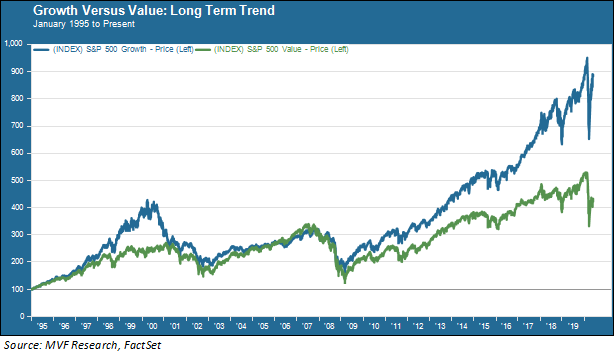

Spare a thought, if you will, for the beleaguered managers of value stock funds. There was a time, and not all that long ago in the great scheme of things, when value managers ruled. “Value outperforms growth over the long term” was as close to a law of nature as existed in the financial industry. Fads may come and go, but the smart money sticks with those companies with low price-to-book ratios best positioned to deliver performance over the full business cycle. Heck, Warren Buffett – the name practically synonymous with “smart money” – is a value investor. But the performance advantage value once enjoyed is long gone, seemingly no more durable than some of the sillier factors littering Wall Street history like the January effect or head-and-shoulders patterns. Consider the chart below, showing the relative performance of the S&P 500 growth and value indexes over a span of 25 years. That’s a pretty decisive advantage for growth (in blue) over value (in green).

Rotating Out of Quarantine

We took you on that 25-year tour d’horizon of value versus growth as a set-up for what was exciting many market observers earlier this week: a seeming rotation from the hot growth stocks that have plowed through Covid-19 without a care in the world to the beaten-down shares of financial institutions, industrial companies and others. “Rotation Tuesday” happened just after the long weekend, and it came on the heels of the weekend’s big news: the re-opening of the economy. From the many pictures – spectators jammed shoulder-to-shoulder at the racetrack, revelers packed onto small patios overlooking Lake of the Ozarks, mask-less beachgoers everywhere – it became clear that for a substantial number of Americans quarantine is over, virus (and fellow countrypersons) be damned.

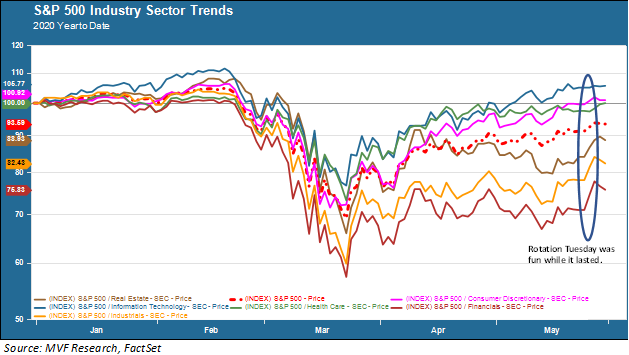

That was the sentiment picked up by the market on Tuesday: anything having to do with quarantine was out, anything related to “back in business” was in. Practically speaking this saw a relatively large jump in those value-oriented sectors – financials, industrials and real estate – relative to their tech and health care counterparts. But the fun was short-lived. In the chart below we have circled the duration of the rotation, which carried through the middle of the week and then started to peter out on Thursday. You can see the brief relative spurt of the underperforming sectors (below the red dotted line signifying the S&P 500) versus the recent outperformers of technology, health care and consumer discretionary.

As a side note we should mention something about that consumer discretionary sector. It may seem counterintuitive that this sector, full of restaurants and retail outlets and the like, would have been doing so well in the middle of a pandemic when so many of them have been shut down. But there is a very simple explanation: one single company accounts for 42 percent of the sector’s total market value. No prizes for guessing this one correctly: yep, it’s Amazon. Bigger and more dominant than ever.

Blame the Fed

So, another rotation foiled. Will value managers ever again see the green shoots of a more durable performance advantage? History would tell you that every dog has its day, and conversely that what goes up eventually comes down. But it may be a fool’s errand to bet on when that will be. Talk to any value manager and you will hear some variation of a common refrain: it’s the Fed’s fault. The argument here is that the central bank’s massive intervention in asset markets has had the long-term effect of distorting the normal practice of price discovery. And price discovery is what value investing is all about: a close analysis of the fundamental growth, margin and quality characteristics of a business and then comparing those fundamentals to the market price of its common stock. When the major dynamic affecting stock prices is not the economy itself but rather the market actions of the Fed, it becomes very hard to apply this analytical discipline in any kind of a meaningful way.

The value investors do have a point. Consider that first chart above, showing the 25-year performance history of the two asset classes. You can see two distinct periods which account for most of the growth advantage. The first was in the late 1990s with the dot-com bubble. But that bubble popped and growth severely underperformed for almost a decade thereafter. Then came the 2010s, the decade of the Fed. This time there was nothing to change the dynamic, because the Fed just kept pumping money into the system (or at least promising that it would pump in money whenever needed). The growth advantage just kept getting larger and larger.

There’s more to the story than that, of course. The economy has also evolved in ways that have played to the natural economic advantages of technology companies, especially those with the ability to establish a dominant platform that reaches across multiple segments of the economy. Commodity prices have fallen, hurting energy stocks, while low interest rates have been a challenge for the profitability of financial institutions (though, of course, that can also be traced right back to the Fed).

Maybe that’s just the price of having the Fed as the market’s buyer of last resort. It provides stability to the overall market, at the cost of losing some of the market’s fundamental integrity. Is it sustainable? So far yes – but nothing lasts forever.