Great Britain does not rule the waves of global finance as it once did. Long gone are the days of the informal club of trading nations bound together by the gold standard and informally headquartered in the City of London. Nonetheless, it remains one of the world’s most developed societies and economies, so what happens there still does, to some extent, reverberate in other corners of the globe. We got a taste of that this week, as credit markets (and to some extent equity bourses) got whipsawed by a massive dose of volatility in benchmark UK interest rates and at one intraday point a record low – as in a 150 year-plus record low – for the British pound sterling against the US dollar.

With all the other problems weighing on markets these days, this was a kerfuffle nobody needed.

Truss Scores An Own Goal

The problem started late last week when the new government of Prime Minister Liz Truss and her Exchequer Chancellor (more or less equivalent to our US Treasury Secretary) Kwasi Kwarteng announced a plan to implement a sweeping tax cut program, worth about £45 billion, on top of a set of fiscal measures to help households with caps on energy bills. The near-uniform response from the world of economists and financial policymakers was: energy caps risky but probably necessary; tax cuts funded by new debt nothing short of insane.

Britain’s headline inflation rate sits around 10 percent, driven mostly by sky-high energy prices that are not due to subside any time soon. The Bank of England, like other central banks, is already faced with the need to raise interest rates to bring inflation back down to manageable levels. A surge of new debt to fund a tax cut, the logic of which seems to be rooted in long-outdated theories of supply side economics, appears to many to be one of the most counterproductive measures a government could take. Hence the near-uniform criticism, including a surprisingly acerbic public comment from the International Monetary Fund of a type normally directed towards recalcitrant emerging markets with underfunded reserves, not a country with the oldest functioning central bank in the world.

The Meltdown in Gilts

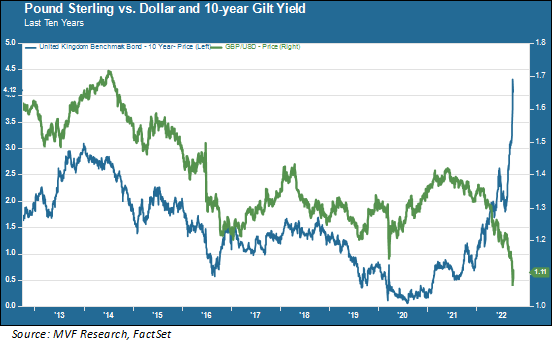

Things went from bad to worse this past Tuesday, as the Truss government refused to back down from their fiscal plans. That day the pound touched a record low level of $1.03. Gilt (UK sovereign) yields skyrocketed, and the market seized up to the point of nearly ceasing to function entirely, requiring an emergency intervention by the Bank of England to buy long-dated benchmark bonds.

Oddly enough, the intervention by the BoE created a rare burst of optimism in world equity markets as the AI algorithms powering short-term trading models misread the British move as a “pivot” to lower rates (it most definitely was not that, as the trader-bots figured out the next day). The underlying story was quite a bit worse, in particular for anyone whose preponderance of personal net worth is domiciled in the UK. The big sellers of gilts during that near-total meltdown were pension funds engaged in a hedging scheme of sorts called Liability-Driven Investment. The basic idea of LDI is to sell off assets when price declines hit a trigger point – the problem being that when enough participants are all doing this at the same time, the price keeps going down, thus necessitating even more selling.

If that sounds familiar to you it may be because you remember the cause behind the stock market crash of October 19, 1987. That was a similar flavor of hedging called “portfolio insurance” – effective if one person does it, calamitous if everyone does it at the same time. In this week’s UK case, though, the underlying money was the politically charged category of pensions – hence the BoE’s decision to intervene before incurring any more wrath from John Bull’s retired mums and dads.

Cross-Border Spillovers

As the seisms in the UK spilled over into world markets this week, central bankers and other financial policymakers are once again faced with the dilemma of trying to steer a clear and consistent policy of fighting inflation while at the same time maintaining financial stability. The brief reprieve in risk assets this week when traders misread the BoE’s intervention as a potential pivot was ill-founded: nothing at this point could be more detrimental to the health of the global economy than for central banks to have to shove aside their anti-inflation policy in order to keep the markets functioning.

There are signs that a modicum of common sense will come back to the Truss government—they are meeting with the Office for Budget Responsibility to reassure markets of their intentions to keep British debt under control. The OBR, an independent forecaster somewhat akin to the Congressional Budget Office, wields considerable influence in shaping markets’ assessment of the credibility, or lack thereof, in government budgets. That would at least be a good start. There are enough genuinely tough problems out there for policymakers and markets to deal with. Own goals are not helpful.