There is a predictable visual theme that accompanies articles covering the quarterly release of China’s GDP growth statistics. Pictures of vast, creepily empty real estate development projects festoon the pages of analytical pieces by the likes of the Financial Times and the New York Times, introducing readers to little-known place names like Luoyang and Tianjin. The imagery helps underscore the central importance of the property sector to China (by some accounts 30 percent of its total economy), as well as the increasingly clear evidence that in this sector supply has vastly exceeded demand.

Feed the Beast

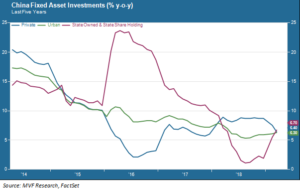

And that trend won’t be changing any time soon. In 2018 China’s growth started to slow noticeably. The stock market fell, fears of the effects of a trade war increased, and consumer activity flagged. As sure as night follows day, Beijing flooded the economy with stimulus, in the form of some $180 billion worth of local government bonds. The effects of that stimulus are evident in the chart below, showing the fixed investment trend over the past five years.

The dramatic uptick in the first three months of 2019 (the crimson trendline) is all about state-owned enterprises, through which that stimulus largesse was funneled. The vast majority of the largesse went right into infrastructure and property projects. There will be plenty more of those sprawling ghost cities for journalists to attach to their future reports.

Cooler Consumers

The spree of property project-bound regional bonds was not the only form of stimulus; there was also a major tax cut aimed at small and midsized businesses to encourage them to invest in their markets. That seems to have had some effect on real economic activity (by which we mean things other than property projects in Nowheresville). Retail sales ticked up slightly in the first quarter after the pace of growth fell dramatically in 2018. This trend is shown in the chart below.

China’s economic authorities for years have been trying to rebalance the economy away from the old infrastructure/property schemata to a more consumer-oriented model. The problem is that every time growth starts to slow, the old playbook comes right back out. Notice in that earlier fixed investment chart the timing of the previous surge in state-owned investment spending: 2015 and 2016, when major parts of the economy seemed headed for a dramatic reversal of fortune. Each time this happens, it expands a credit bubble already of historic proportions. China’s debt to GDP ratio was 162 percent in 2008; it grew to 266 percent by last year. Waiting for the rebalancing is like waiting for Godot, while the debt piles up.

It Matters for Markets

The principal headline in this week’s data release was that the overall rate of GDP growth was somewhat better than expected, at 6.4 percent. The reaction among much of the world’s investor class appeared to take this at face value and chalk up one more reason to keep feeding funds into the great market melt-up of 2019. But those same analytical pieces featuring Luoyang’s empty towers point out that, as much of the economic stimulus was front-loaded in the first quarter, a double dip may well be in store. That may matter for markets at whatever time the equity rally takes a pause from its blistering year-to-date pace. Not everything matters for markets, but the performance of the world’s second largest economy is one of the more reliable attention-getters, at different times for better and for worse. The durability of the current stabilization will be something to watch heading into the year’s second half.