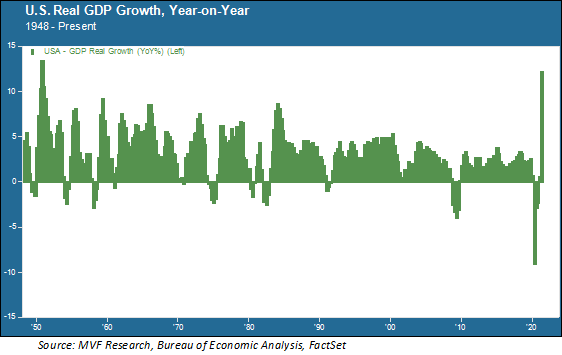

We have known for some time now that the second quarter GDP report was going to be a barnstormer, for no other reason than the point of comparison. The second quarter of 2020 saw the lowest year-on-year contraction since the Bureau of Economic Analysis started keeping regular records in 1948. It was only to be expected, then, that the Q2 2021 number was going to outshine any period in recent history. The 12.2% gain from the same quarter in 2020 was indeed the fastest rate of growth since 1950. The chart below shows the wacky distortions caused by the pandemic-related shutdown and reopening.

Right Back Where We Started From

With that second quarter recovery, US GDP has now recovered all the value lost from the downturn. China got there ahead of us at the end of 2020, and the Eurozone will most likely get back to square one by the end of this year. Second quarter GDP growth for the Eurozone, released this morning, was 13.7 percent from Q2 2020, an upside surprise relative to what economists were forecasting. Going forward, the quarterly output numbers will likely start converging towards recent pre-pandemic growth rates.

The question is whether anything is going to reverse the long-term decline in the growth rate, also visible in the chart above, over the succession of economic growth cycles from the 1980s on. The average year-on-year growth rate from 2010 to 2020 (prior to the pandemic) was 2.2 percent. From 1980 to 2010 the average was 2.8 percent, and from 1950 to 1980 it was 4.0 percent. Part of this long-term trend is simply the share of global output contributed by the US. For the two decades after the Second World War the US was the sole economic superpower in the world and its primary source of value-added goods and services. Successive competitive challenges from Japan, Europe and most recently China and other Asia Pacific economies have changed the game; it is extremely unlikely that any single country will ever again enjoy the kind of undisputed supremacy the US enjoyed during the Bretton Woods period of the late 1940s to the early 1970s.

That Other Story of the Week

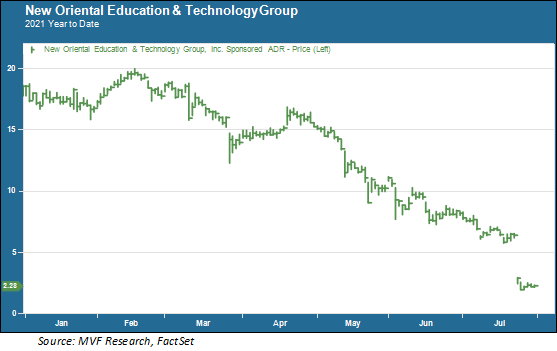

Thinking about what that near-future US GDP growth trend might look like brings us to another big story generating headlines this week, which was also the subject of our weekly commentary last Friday. Shares in China and Hong Kong plummeted earlier in the week on continued reports of a clampdown by Beijing on companies with foreign securities listings and in particular those in the $100 billion education sector. Consider the unhappy investors holding exposure to New Oriental, a leading provider of tutoring and test prep services. This past Monday ADRs in New Oriental plunged to a level below two dollars, representing a 90 percent – not a typo – fall from their high for the year back in mid-February (they had recovered slightly by the end of the week). The chart below shows this gruesome trajectory.

How, you might ask, is the plight of a Chinese test prep company relevant to a discussion about US GDP growth rates? It comes back to the question we floated in our piece last week: why does China seem willing to throw some of its most visibly successful tech and related sectors to the wolves? If Beijing is not particularly worried about the pain being felt in consumer-facing Internet, financial technology and educational technology companies, then what is it spending time worried about? The answer might be found in certain sectors featured with increasing prominence on the Shanghai, Shenzhen and Hong Kong exchanges: biotechnology, clean energy and semiconductors, to name three.

Who Wins the Future?

The thinking in Beijing, rightly or wrongly, is that the economic future will be won in areas like this more than they will on who has the snappiest games or the most frictionless e-payment app or the most addictive social media platform (or, per Mark Zuckerberg, who owns the “metaverse” – look it up!). China is clearly moving in that direction as it looks to rebalance its own GDP away from the infrastructure and property formula that has delivered much of its own performance over the past twenty years. It may or may not work – but China-watchers will need to pay more attention to Shanghai and Hong Kong than to New York as this strategy unfolds.