We came across one interesting little data point this week amid the usual news avalanche. The US birthrate reached a 30 year low in 2017: fewer babies were born here last year than any year since 1987. What caught our eye was the odd timing. Birth rates tend to be loosely, but positively, correlated with economic growth (rising during good times and falling when growth goes south). 2017 was the eighth year of what is now the second longest economic expansion in US history. And yet…fewer babies. The fertility rate has fallen from 2.1 kids per woman of childbearing age a decade ago to 1.8 today.

The Growth Recipe

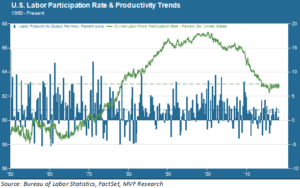

Population data like birth rates don’t typically figure in to short term market movements; we would feel confident in opining that these latest reports, which came out yesterday, did not figure into the day’s movements of the S&P 500 or the 10-year Treasury yield or the price of a barrel of Brent crude oil. But they do matter for the bigger picture, which is why every now and then they will show up in one of our weekly commentaries. Population growth is one part of the long term economic growth equation, along with labor force participation and productivity. Right now, all three of these variables are either negative or stagnant, which puts a big asterisk next to that longevity record for the current recovery. What good is an expansion if the rate of expansion is, by historical standards, so low? And while there may not be much we can do about broad population trends, what is it going to take to bring back higher productivity? The chart below shows the long term trends (since 1950) for productivity and labor force participation.

This is a useful chart for understanding what we mean when we talk about “long term growth.” There are two notable dynamics here. The first was the remarkable burst of productivity that came in the immediate postwar era. This was the heyday of Pax Americana, when our factories and the goods they produced were the envy of the world. As the chart shows, the average rate of productivity (the thin blue vertical columns) was substantially higher during this period than it has been at any time since. Productivity stared to decline in the early 1970s as the economy globalized and other nations – notably a rebuilt Germany and Japan – caught up.

But another trend kicked in around the same time that kept the growth going. This was labor force participation, represented in the chart by the green line. The baby boom generation started to enter the workforce, and so did women, heralding the arrival of the two income household as mainstream. Labor force participation went on a massive surge that didn’t crest until the late 1990s. Then, another productivity boom (though less impressive than that of the 1950s-60s) happened in the late 1990s and early 2000s, this one driven mostly by the delayed impact of information technology in the office and new business processes, like just-in-time inventory management and enterprise resource management, that made efficient use of all that new computational capacity.

Alexa, Make the Economy Grow

Which brings us to today. The decline in the labor force participation rate appears to have stabilized at a level close to that of the late 1970s, while productivity for the last decade is the lowest since record-keeping began in 1948. Imagine for a moment that you are looking at the above chart in 2030, twelve years from now. Or even farther down the road, in 2040. What will it look like?

As for labor force participation, we have some clues in those population trends we observed in the opening paragraph of this commentary; namely, the US population is ageing and the fertility rate is moving farther away from the replacement rate (where each new generation has enough children to replace the outgoing generation). We are not likely to see another phenomenon akin to the sudden surge of two-income households in the 1970s and 1980s to boost participation rates.

That leaves productivity as the only variable with potential energy. If our kids and their kids are looking at this chart and remarking on the great growth cycle of the 2020s, it will be due to a new wave of productivity that we have not yet seen but that may well be lurking under the surface. Artificial intelligence, immersion reality, quantum computing…these are technologies that are known but that have not yet shown themselves to translate to economic growth. But that may be simply a matter of time. The computer technologies developed in the vast mainframe labs of the mid-20th century didn’t flex their commercial muscles until much later, after all.

Or maybe our grandkids won’t care about this chart at all. “Economic growth” didn’t become the go-to proxy for “quality of life,” with all the attendant statistics like GDP, inflation and labor productivity, until after the Great Depression (which is why all the official records for these numbers didn’t start until the 1940s). Maybe some other metric will matter more to them…and to us, in our advanced years.

In the meantime, though, a healthy dose of productivity would be a nice antidote to those baby blues.