Britney Spears and ‘N Sync were blowing up the charts, President Clinton was dominating the headlines in a most unfortunate way, and households all across the country were lovingly attending to their pet Furbys. 1998 seems a world away from that which we inhabit today, seventeen years later. Yet the economic headlines, if not exactly repeating, do seem to rhyme a bit. There are some history lessons here worth bearing in mind as our attention turns to managing our portfolios through the second half of this year.

Here We Go

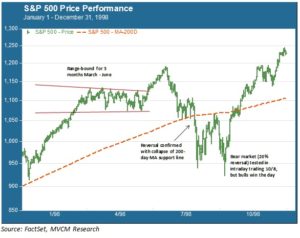

In 1998 we were well into the multi-year bull market in US equities that began in 1995, but there were serious concerns elsewhere in the world that investors feared would spill over and spoil our party. Following the collapse of the Thai baht in the summer of 1997, East Asian currencies fell by as much as 80 percent against the US dollar over the next year. Their stock markets were likewise pummeled as foreign portfolio capital made a mad scramble for the exit. The S&P 500, shown in the chart below, was stuck in a three month rut as the 1998 calendar flipped to June. It would enjoy an upside breakout through the first half of July, but more ugliness lay in store.

Shocks…

Summertime ended early for traders in 1998 with word that Russia was defaulting on its sovereign debt. Russian government bonds (GKOs) with their generous yields were a favorite asset holding among foreign investors. After the Russian government liberalized the GKO market in 1997, foreigners grabbed around 30 percent of the total market. The likes of Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley opened Moscow offices and competed furiously for mandates, right up to the end of the party on August 17 when the government announced its intention to default.

Nowhere was the demise of the Russian bond market felt with more dismay than in the plush offices of Long Term Capital Management, the prominent hedge fund run by ex-Salomon Brothers star trader John Meriwether and options guru Myron Scholes, one half of the Black-Scholes formula that begat the modern derivatives industry. LTCM’s exposure to Russia led to its bankruptcy and – foreshadowing the Lehman Brothers menace of ten years later – fears of an industry-wide contagion. The specter of a bear market loomed, and indeed the 20% peak-to-trough threshold was tested in early October.

…and Shock Absorbers

As we all know now, that bear never got traction. Policymakers and bankers figured out how to put LTCM out of its misery without taking the rest of the industry down with it. All hailed Messrs. Greenspan, Rubin and Summers as the “Committee to Save the World”. With the US economy continuing to hum along nicely and with continuing problems elsewhere in the world, US stocks once again looked like a pretty good comparative bet. The party would roar along for a couple more years, until “Oops! I did it again” would come to describe the vibe in the worlds of both pop music and capital markets in 2000. Investors who bailed out in the late 1998 turmoil missed out on another 59% of capital gains from the 10/8 trough to the March 2000 peak.

Lessons for Today

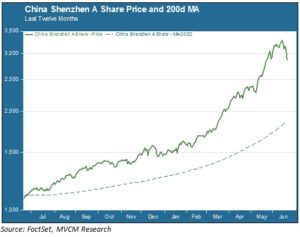

What can the 1998 experience tell us about today? Clearly the world is a different place. The US economy is growing, with low unemployment and tame inflation, but it is not growing at anything like the pace of the late 1990s. Still, the US continues to look pretty good compared with other parts of the world. The Greek crisis could yet throw cold water on the recent spate of relative good news in the Eurozone. China’s domestic stock market is a bubble showing an unhealthy uptick in volatility, as seen in the chart below.

The Shenzhen A Share index booked a year-to-date gain of 122 percent on June 12, but experienced back-to-back losses of 3.5 percent and 5.9 percent over the last two trading days. China – which comprises about 25 percent of the MSCI Emerging Markets index – has done the lion’s share of the lifting in pulling EM stocks up this year. A collapse in Chinese equities would be likely to bring the rest of the asset class down with it. The herd effect of portfolio capital that tanked emerging markets in 1997-98 is alive and well.

Greece and/or China could be a catalyst for the long-expected pullback in US stocks. The S&P 500 has not closed 10% or more below the last peak since 2011. But – and here is where we see the usefulness of the 1998 parallel – any such pullback is in our opinion likely to play out relatively quickly and present the potential for further gains before this bull fully plays out. Investors have to put their money somewhere. If the rest of the world looks more unsettling than our home market – and this in the context of a bond market that is, if anything, harder to navigate than equities – we do not see a compelling script for a secular bear in US stocks. Navigating pullbacks requires discipline, but history shows there can be rewards for those who keep their emotions in check.