FOMO – fear of missing out – has been around for as long as members of the human species have traded with each other. In the seventeenth century there was a mania among the good citizens of Holland for tulip bulbs. At one point during this frenzy the price of a single bulb – admittedly pretty but still nothing more than a flower – was worth more than the price of a home along one of Amsterdam’s canals. One century later, the center of global finance had moved from the Netherlands to Great Britain. A good many British investors fell prey to the South Sea Bubble, a faraway enterprise that sounded too good to be true because…well, it was too good to be true, as in it didn’t even exist.

And so it has gone through the ages and into the present day. There is something consistent about all these speculative bubbles. They start organically, gain traction by word of mouth and at some point reach the kind of momentum that gets everyone talking. Eventually they will gain enhanced legitimacy when self-styled experts weigh in to say, no, this is not a bubble for reasons X, Y and Z. At the height of the stock market mania in 1929 Irving Fisher, one of the most renowned economists of the day, opined that share prices had reached a “permanent plateau” from which they could only go higher. Which they did, until October 1929, and then they didn’t.

Think of all the institutional giants and their endorsement of the “New Economy” and its crazy valuations in March 2000, just before the Nasdaq took an 80 percent nosedive. Or all the seemingly sophisticated investors who bought into the Bernie Madoff scam of a “guaranteed” 15 percent and no risk.

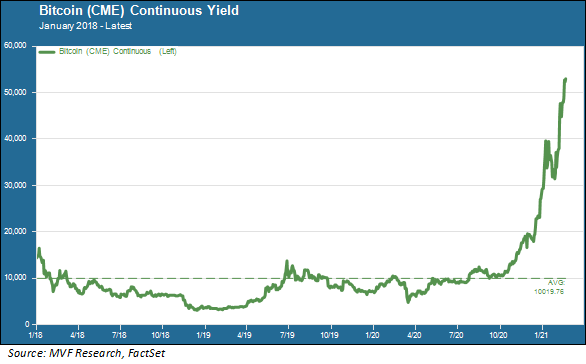

All of which brings us to bitcoin. OK, let’s just get it out of the way. Here’s the chart that explains why every asset manager on Earth is now required to have a stated position on bitcoin.

Pretty impressive, no? And hey, if Elon Musk loves bitcoin (and he most assuredly does), then it must be a wise investment, right? (Refer above to the bit about self-styled experts weighing in to explain why something that looks like a bubble really isn’t a bubble). Motley Fool – probably the only company that grew up in the 1990s Internet era and has not even once changed its logo – also made a big to-do this week about adding bitcoin to its holdings. Social media being what it is, now everyone is supposed to either pronounce themselves on the bandwagon or defend to angry Twitter mobs why they are not.

We’re not here to judge. As asset managers, we are just here to evaluate whether there is some actual merit to the basic idea of bitcoin. What exactly is this thing – what actual function does it serve? Bitcoin is a digital currency (the popular phrase is “cryptocurrency” but that doesn’t actually mean anything other than a digital currency based on the decentralized technology of blockchain). So our evaluation focuses on how well bitcoin does what a currency is supposed to do, which is basically one or more of three things: a unit of measure, a means of exchange, and/or a store of value. Either bitcoin is a solution to an existing problem in one of these areas, or it is simply a solution looking for a problem.

Unit of Measure

How well does bitcoin function as a unit of measure? To answer that question, simply look at the chart above, to something that within the space of just two years alone has traded between $5,000 and more than $50,000. How is anyone supposed to measure anything using Bitcoin as a yardstick?

Or think about it like this: when you look at that chart, what is the actual unit of measure being employed? That would be US dollars, which does actually serve as a unit of measure. If a couple is out at a furniture store pricing a new sofa, they don’t think about how many bitcoins the sofa costs. They think of the cost in terms of dollars (if the couple happens to own a few bitcoins they may think, hey, we can cash in a bitcoin to buy the sofa…and then buy a Tesla with the remaining dollars!).

Until and unless people start thinking about their everyday purchases in bitcoin rather than in dollars, euros or yen, then bitcoin is not serving the function of a unit of measure.

Means of Exchange

Bitcoin cheerleader Elon Musk says that he plans to start letting people pay for Teslas in bitcoin. So is it coming into vogue as a means of exchange? Kudos to Mr. Musk for his bravado, but look again at that chart. Now put yourself in the position of being the owner of a store selling things priced in bitcoin. How are you going to manage your profit margins?

What about the idea of bitcoin as a “digital wallet?” There’s a lot of hype out there, as if suddenly digital payment systems have moved into a new age because of bitcoin. But wait. Digital wallets have been around for years. Apple Pay, PayPal, heck, even Visa and Mastercard, which have been around since plastic started to replace cash in the 1960s, have rolled out increasingly sophisticated digital wallets. There is nothing inherent in the technology behind bitcoin that makes it a superior means of exchange to any of these other financial technologies. In fact, processing capabilities for bitcoin tend to be somewhat clunkier than the hyperspeed capabilities of existing digital payment systems.

And there is a basic problem with those bitcoin wallets based on the underlying blockchain technology: if you lose the passkey that unlocks your bitcoins, you lose your bitcoins. Imagine that if you forget your Apple password not only could you not use Apple Pay, but you couldn’t even gain access to the bank account linked to your Apple profile! Now imagine that there is not even any tech support help to get you back to your money. How effective would that be as a means of exchange?

Store of Value

So that brings us to the final use of a currency: store of value. This is a trait shared by currencies (which are simply financial commodities) and physical commodities alike. An asset has a store of value if it has a defined use. That use is easy to define for industrial metals, like copper and nickel, or for sources of energy like crude oil and natural gas. Ditto for agricultural products like soybeans and wheat. Then there are precious metals, for which the actual practical uses are less clearly defined but which over the centuries have been seen as stores of value due to their relative scarcity. Modern-era national currencies, which for the most part are so-called “fiat currencies,” have a store of value simply because they are deemed to be, and widely accepted as, legal tender for exchange in their countries (or regions) of origin.

One of the arguments made about bitcoin is that it is a store of value because there is a limit – a ceiling – to how many can ever be produced (this is where you might hear the term “digital gold” applied to bitcoin). That was one of the original design intentions when the currency first came out in 2009. But hold on. Just because there is a limit to how many bitcoins can ever be in circulation does not mean that they are rare. Even today there are at least ten or fifteen other “cryptocurrencies” that use the same underlying technology, all of which would be fungible in any world that would use cryptos as a means of exchange. If there are variations between bitcoin and other cryptos like dogecoin or ethereum, they are more like differences between South African-mined gold and Russian-mined gold, or Kansas wheat versus Illinois wheat. Slight variations, maybe, but otherwise fungible. That’s what makes them commodities.

Bitcoin and Armageddon

Will bitcoin ever have a better claim than it does today on being a viable and necessary currency? It is conceivable. If the socio-economic stability of the US, the European Union, Great Britain, Japan and China were all to disintegrate to the extent that all of their respective national currencies ceased to be worth the paper they were printed on, and nation states generally collapsed into a worldwide Time of Troubles, then arguably something like bitcoin could be the only viable means for human trade and commerce.

Or, alternatively, such an apocalyptic scenario could also involve the crashing of the world’s electrical grids and with it all the digital technology. As it is, the mining of bitcoins is incredibly energy-intensive. Cryptocurrencies are no friend of the environment (which makes Elon Musk’s fascination with bitcoin somewhat ironic). So would it be bitcoins or barter? Such are the shortcomings of wild speculation.

Bitcoin and the Super Bowl Coin Toss

Our assessment of bitcoin, and so-called cryptocurrencies in general, is that they fall squarely in the realm of pure speculation rather than being a viable strategic asset for purposes of long-term portfolio performance. Pure speculation means the world of bets on sporting events or rolling the dice on the craps table in Las Vegas. A bet on bitcoin going from, say, $50,000 to $100,000 or more is just that – it’s a bet. It is something that has a probability greater than zero and less than one hundred. Just like rolling sevens or having the coin come up heads or Tampa Bay upsetting the Kansas City Chiefs. Speculation is fine, for those who enjoy a bit of a thrill. But it’s not asset management, at least not the way we define it.