We continue this week with our review of 2023 at the halfway mark, today’s focus being the very strange world of fixed income. You know the mantra because you’ve heard it from us thousands of times: bonds for safety, equities for growth. We expect that will still be true in the long run, but the bond market has not been anything like an oasis of calm so far this year.

The Great Mispricing

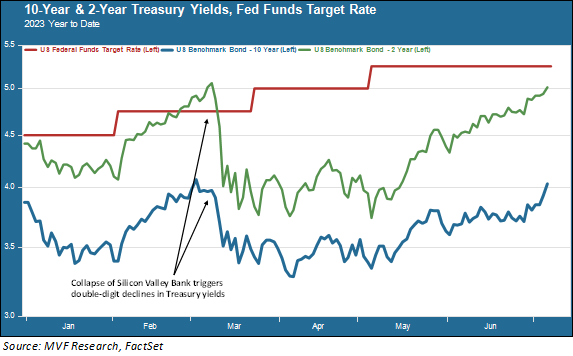

Fixed income markets had been volatile before the sudden collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in early March set off a mini-panic about the stability of the banking sector. But that event sent bond yields plummeting, with the yield on the 2-year Treasury note falling more than 20 percent in the space of three trading days.

20 percent is no small thing; imagine the frenetic news coverage that would accompany a similar magnitude of price change in the S&P 500. The financial media has something of a blind spot when it comes to chronicling yield fluctuations in the bond market. The question is why such a major reset took place in an environment where the Fed was continuing to make it very clear that nothing had changed regarding its monetary tightening program. Note in the chart above what doesn’t go crashing to earth in the wake of the banking problems: the Fed funds rate (crimson trendline).

Rate Cut Fantasies

What happened here was that the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank fed into a pre-existing narrative among fixed income investors that we never understood (and about which we have written copiously in these pages over the past few months. This narrative held that not only was the Fed just about done with raising rates, but it was on the cusp of cutting them. To repeat: this was before the banking sector troubles. When SVB collapsed, the Fed was a key part of the consortium of agencies that worked out a plan to protect depositors. Bond investors, apparently captive to the behavioral finance trap of recency bias, immediately saw the resurrection of the “Fed put” – the central bank’s tendency of recent years to rush in with a flood of liquidity every time something went pear-shaped in the market. Some in the fixed income commentariat opined that the Fed was going to scrap tightening altogether and immediately cut rates. As the above chart shows, the confusion about this didn’t go away – it persisted throughout the rest of March and April as bond yields mostly went sideways, but with a much wider up-and-down band of volatility than is normally the case for what is supposed to be the world’s safest asset.

Getting the Memo (Maybe?)

Things have settled down a bit since then, in the sense that there is some direction to interest rate trends now, rather than the directionless volatility of March and April. That direction, as the chart clearly shows, is upwards. The Fed not only did not reverse course on monetary tightening after the banking sector problems, but it continued to confront challenging data from inflation reports and the labor market, suggesting that there is more work to be done in getting consumer prices back to target levels. The June meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, held just a couple weeks ago, showed that even while the Fed did pause for that meeting, almost all the Committee members expect not just one, but probably two more rate hikes before the end of this tightening regime. All the talk of imminent rate cuts has finally, it would seem, dissipated into the ether.

That doesn’t mean an end to the confusion, though. For a world in which core inflation is over five percent and the unemployment rate is just 3.6 percent, the inverted spread between short-term and intermediate-term bonds continues to be a puzzle. You can see in the above chart that the inversion is in fact wider today than it was a couple months ago – in fact it is wider than at any time since the draconian interest rate policy of the Volcker Fed back in the early 1980s. An inverted yield curve is supposed to be the most reliable predictor out there for an impending recession. Yet the recession – if it is indeed to come – keeps getting pushed back by the consistently strong macro data.

Two more increases in the Fed funds rate, if they in fact are to happen, will bring that overnight rate up to a range of 5.5 – 5.75 percent. In a normal world, that should imply likely further upside for other interest rates from where they are now (the 2-year is a bit over five percent and the 10-year is just over four percent as we write this). We have been approaching our duration positioning cautiously, with this dynamic in mind, and see good opportunities in the coming weeks for locking in attractive yields. But normal? This bond market is anything but normal.