Bonds were all anyone in financial circles could talk about as the post-Labor Day market cranked into gear. The US 30-year Treasury bond was nudging five percent, while UK gilt yields soared past levels last seen in the late 1990s. Stagflation-induced bond weakness was topic number one as the customary Brady Bunch-like panels of talking heads gabbed on CNBC and Bloomberg News. What was the Fed going to do – even if it were to manage to remain independent – when its two tasks of maintaining stable prices and promoting maximum employment were in direct conflict with each other?

Labor Pains

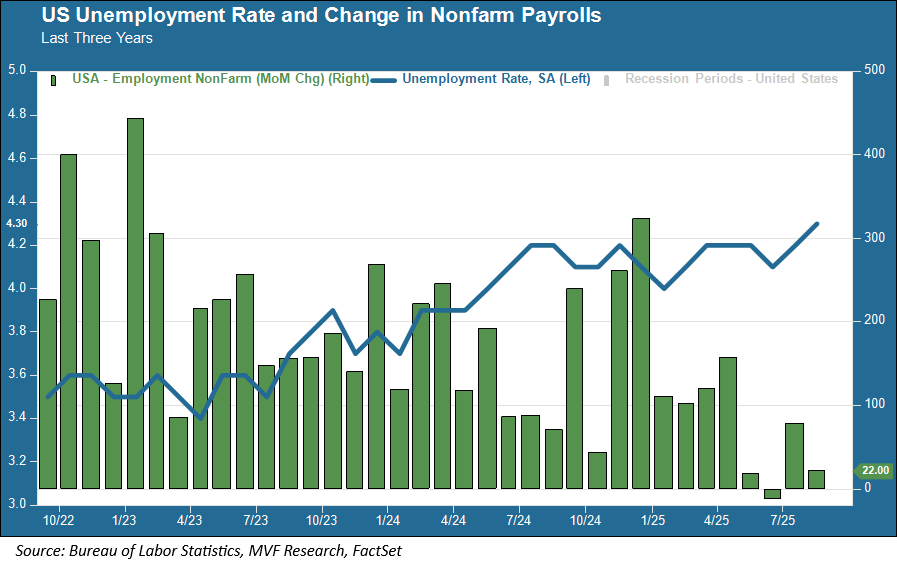

With today’s jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, we probably have a solid answer to that last question, at least for the near term. The August employment numbers validated the sharp downward trend seen in the July report – yes, the one that came out just one month ago with numbers grim enough to put the agency’s head in the crosshairs of a displeased White House (sadly for the administration’s spinmeisters, there is no BLS head available for them to fire this month). In fact, the previous report looks even worse now, with a net negative revision to the June and July numbers. For the month of August, nonfarm payrolls grew by just 22,000 (versus economists’ forecasts of 77,000) and the unemployment rate crept up to 4.3 percent, its highest level since 2021.

The weak jobs report increases the likelihood of a Fed funds rate cut when the Federal Open Market Committee meets the week after next. Market observers see a 0.25 percent rate cut as a near-certainty, barring an unexpectedly red hot inflation print when the Consumer Price Index report comes out next Thursday. And that, in turn, has taken the edge off the bond market mini-freak out earlier this week. Yields have come down across the full spectrum of maturities, with the 2-year Treasury yield now below 3.5 percent, the 10-year at 4.08 percent and the 30-year long bond dropping down below 4.8 percent after that dalliance with five percent earlier in the week. Stock markets are getting an injection of rate cut-driven animal spirits as well, with the S&P 500 up half a percent just after today’s market open

Yes, But Stagflation

The short-term palliative of rate cuts may not last for long. We won’t have a full inflation picture until next week’s CPI and PPI reports come out, but last Friday’s Personal Consumption Expenditures report (the inflation number most closely watched by the Fed) showed core PCE ticking up to 2.9 percent, still far away from the Fed’s two percent target rate. As consumer-facing companies wrap up their second quarter earnings reports, more and more of them are affirming that the days of finagling supply chains and inventory levels are coming to an end. Consumers will be seeing more of the higher costs brought about by tariffs, and may finally understand that tariffs are, in effect, a sales tax.

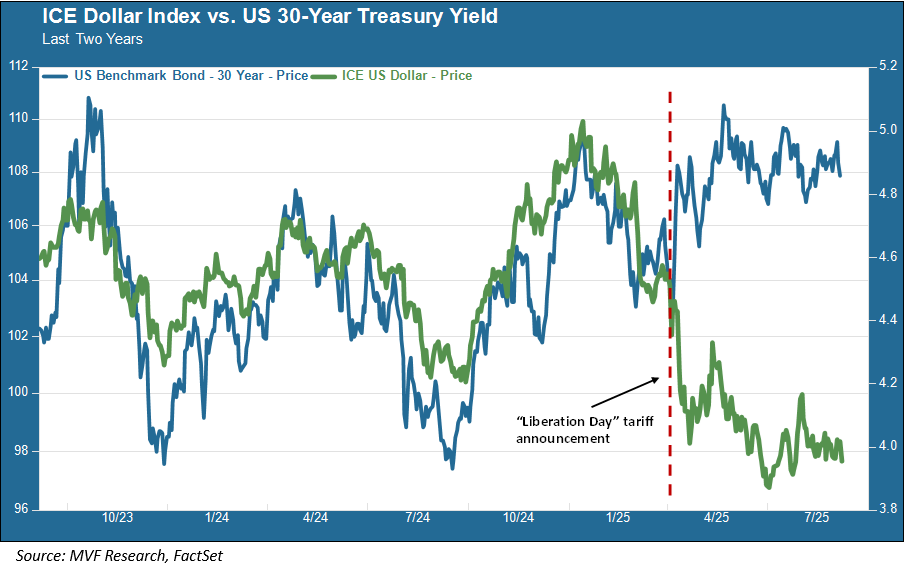

So despite the late-week reprieve in yields, we will not be surprised to see the 30-year bond head back up towards five percent and perhaps wind up on the other side of that round number threshold. Of still greater concern is that this trend is happening at the same time that the US dollar is weakening against other currencies. One of the most dependable trends in financial markets over the years has been the positive correlation between the dollar and the long bond yield. The April 2 tariff announcement broke that trend, and it hasn’t recovered since.

Normally, rising yields on what is supposed to be the world’s safest asset makes that asset more attractive and thus boosts the value of the dollar as investors pile in. A weak dollar, on the other hand, suggests that the brand value of that “world’s safest asset” nomenclature is not what it used to be, and the potential for stagflation threatens to push yields even higher. A cut to the Fed funds rate – or even successive cuts as the more dovish FOMC members want to see – is not by itself going to offset the threats to long-term yields brought into the spotlight earlier this week. Caution remains the watchword when it comes to long duration exposures.