The Fed cut interest rates again this week in a widely telegraphed and entirely unsurprising move (though not without one notable dissent from Cleveland Fed head Beth Hammack, who voted to keep the target Fed funds rate at its current level). Somewhat more surprising was the change in projections by members of the Federal Open Market Committee as to the likely cadence of rates in the year ahead. Back in September, the median estimate for 2025 rate cuts was four, which would give us a target Fed funds rate in the range of 3.25 – 3.50 a year from now. This week, though, the FOMC dialed back these expectations to just two cuts. Citing a stronger than expected economy, a well-behaved labor market and inflation proving to be somewhat stickier than desired, Fed chair Powell explained that current conditions give the central bank the ability to proceed cautiously. Left unsaid by Powell – but harped on by pretty much every journalist in the room at the post-meeting press conference – was uncertainty about potential risks to the present economic equilibrium once the new administration gets going with its plans come January.

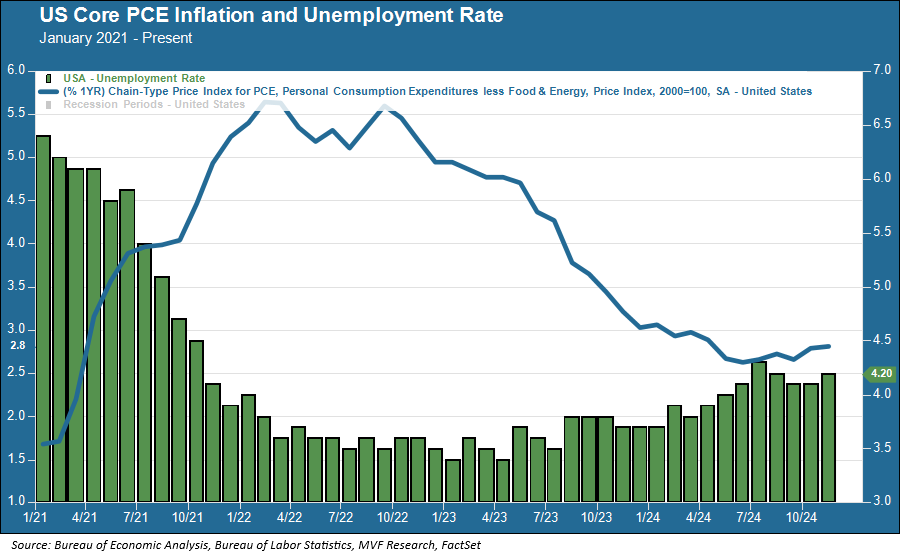

The chart above encapsulates the rationale for putting on the monetary policy brakes. The Fed’s dual mandate calls for maintaining stable prices and maximal employment. Back in mid-late summer, inflation (the blue line in the chart) seemed to be on a reasonably steady trend towards the target two percent rate while unemployment (the green columns) was creeping higher. Concern about the jobs market was starting to overshadow what had been for the past three years a singular focus on inflation. The past several months, though, have given cause for pushback. Inflation seems to have leveled off and even ticked slightly higher on a year-over-year basis, as you can see in the chart. Core (ex-food and energy) Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE), the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, has been stuck between 2.7 – 2.8 percent since August (though core PCE for the month of November as reported this morning grew only 0.11 percent, which was lower than economists’ estimates). Meanwhile, the unemployment rate has steadied and backed off somewhat after reaching a three-year high of 4.3 percent in July. Earlier this week we also got word that third quarter real GDP grew at an upwardly-revised 3.1 percent. Put together, all these indicators suggest that the risk of a somewhat higher Fed funds rate choking off growth and bringing about a recession is fairly low. Tapping on the brakes, by this argument, is warranted.

Then there are all those questions about what lies in store when the new administration takes over in January. Judging from what has been going on in Congress this week, a decision to wait and see without leaping to hasty judgment would seem to make sense. A continuing resolution to keep the government open past a Friday night (tonight!) deadline, which had bipartisan support, was shot down. A Plan B funding bill whipped up yesterday also failed, with 38 Republicans joining almost all Democrats in voting against the bill (this despite its support from the president-elect). Plan C is apparently circulating out there somewhere, maybe? Anyone? In short, there appear to be enough fissures within the Republican Party itself, let alone opposition from across the aisle, to cause anyone to wonder how much new policy good or bad is ever going to make its way into law.

Fortunately, the Fed has time on its side given where the economy is today. Markets reacted negatively in the immediate wake of the FOMC decision on Wednesday, but today’s better than expected inflation numbers from the PCE report seem to have taken the edge off a bit. With plenty of potential for uncertainty ahead, it’s better to keep at least some powder dry while you can.