The big news after last month’s National People’s Congress in Beijing was the announcement by Premier Li Keqiang of the government’s intention to set a range, rather than an individual target, for annual real GDP growth. The range was to be between 6.5 and 7.0 percent, seen as striking a balance between the admission that a steady rate of seven percent, the previous target, was not sustainable, while still delivering enough top-line growth to reach the country’s GDP targets for 2020. Today China released its GDP results for the first quarter of 2016 and – lo and behold – the number came in at 6.7 percent. Observers met the release with the usual skepticism over how much the reported figure varied from what is actually going on in the world’s second largest economy. We’re less concerned about whether the “real” top line is 6.7 or 7.0 or even 5.5 percent, and more concerned about what recent data tell us about the progress, or lack thereof, towards China’s much ballyhooed economic rebalancing.

More Bridges to Nowhere?

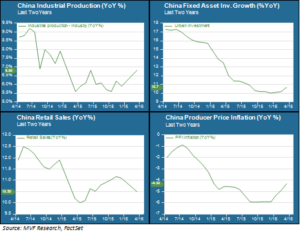

Specifically, much of the data released since the March NPC meeting points to an apparently deliberate decision on the part of Beijing policymakers to reach for the elixir of investment-driven stimulus – the key growth driver for much of the past 10-plus years – as a way to head off concerns that efforts to rebalance towards a more domestic consumption-driven economy may be falling short. Those concerns have manifested in recent months in the form of massive capital outflows and a resulting 20 percent decline from peak foreign exchange reserves. Premier Li’s NPC remarks reflected the view that a sugar fix is the best response. Markets took note: iron ore prices jumped by a ridiculous amount on the Monday after the NPC, and commodities generally surged in anticipation of a pickup in China demand. Were they right? Consider the chart below showing other recent key data releases.

Among these four charts, you can see the sharpest reversal of recent trends in industrial production and wholesale prices, both of which came in comfortably ahead of analyst expectations. Fixed asset growth – a key metric for China’s activity in infrastructure and property development – is still nowhere near the levels of recent years, but has actually increased for the first time since 2014. Meanwhile the growth rate of retail sales, an important benchmark of consumer activity, is lower than at any time in the past twelve months.

Corporate Debt – China’s Mountain Dew

Fixed asset investment doesn’t happen without infusions of new debt capital. New bank loans in China are up $351 billion in March, on the heels of an even brisker pace of $385 billion in January new loan creation. That January number represents the fastest pace of monthly loan growth on record. While January is often the busiest month of the year for new loan creation, with newly-approved projects tapping their sources of credit financing, the strong follow-up in March raises expectations that China’s outstanding debt will continue to set new high ground. Bear in mind that China’s total non-financial debt to GDP has soared from around 100 percent of GDP in 2009, at the outset of a new bank lending stimulus program, to 250 percent of GDP today.

The aggregate level of debt is not the only concern; much of the lending is still tied to the so-called “zombies” – troubled state-owned companies whose loans constitute a potentially significant credit quality problem for the banks that originate them. Bankruptcies and loan write-downs are a delicate matter in China, and reminiscent of the chronically inept way Japan’s financial institutions and regulators tried to deal with that country’s nonperforming debt problems in the 1990s.

When the Sugar Wears Off

All sugar highs come to an end, a fact not lost on Beijing’s Mandarins. We do not think it is on anyone’s agenda to try and embark on another decade of hypergrowth fueled by bank loans and fixed asset investment. The Mountain Dew is meant to buy some time and give the urban services sector a chance to establish enough momentum to take over as the economy’s growth engine. This is China’s own version of “kick the can,” a game in which almost every globally significant economy has indulged over the past seven years. For the time being we expect the China story to be net-neutral to positive in its contribution to the overall market narrative, premised on expectations of no imminent hard landing and a stimulative effect on commodities prices. Come autumn, though, policymakers may need to show they have an effective antidote to the sugar high.