It is once again that silly day of the year when news organizations dutifully report on the weather forecasting acuity of that beloved groundhog in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania. The quadrupedal meteorologist apparently signaled an early spring, so three cheers for that. Here’s where we don’t see any signs of an early spring: China. The China Shenzhen A Shares index is rapidly approaching a bear market just from where it started the year; down 19 percent since the beginning of January. The index is already well into bear territory overall, down 35 percent from the latest peak reached in January 2023.

It’s a completely different story in the Asian country whose population surpassed that of China last year. India’s stock market is in ruddy health, as is the overall economy, which has been putting in annual real GDP growth rates over six percent and undertaking reforms that have encouraged new flows of both foreign direct investment and portfolio capital.

The Recovery That Wasn’t

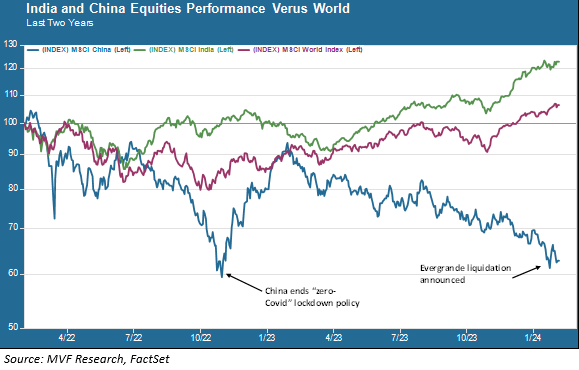

Let’s turn the clock back to 2022, when China was firmly wedded to its unrealistic policy of “zero-Covid,” shutting people up in their apartments and closing shipping ports while the rest of the world was working its way back from the pandemic. Things were so bad as to finally spur widespread protests in the fall of that year, with citizens risking falling afoul of Beijing’s heavy authoritarian hand by coming out in the streets to register their discontent. The government finally backed down and terminated the lockdowns. At that point foreign investors turned into super-charged China bulls, as the above chart shows.

But the optimism was misplaced, and for reasons that the starry-eyed investors should have seen. China’s economy has long been driven by the property and infrastructure sector, which regularly contributes about a third of the country’s total GDP output. It would not be correct to pronounce that sector in freefall; rather, it has been a slow and tortuous decline ever since the giant development firm Evergrande missed its first international debt payments in the summer of 2021. A succession of defaults and near-defaults have ensued, claiming the property sector’s biggest names. Without a healthy consumer sector to offset the property and infrastructure declines, China’s overall economic performance has been subpar. Just this week, the long-running tragicomedy of Evergrande came to a pathetic end when a last-gasp restructuring effort failed and a Hong Kong court ordered the once-and-for-all liquidation of the company.

Davos Man and Hindutva

Over in India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his BJP party are almost certain to win re-election when national elections are held this spring. Modi has been in power since 2014, and his rule has been a curious mix of policies. On the one hand, the BJP’s economic policies have been very foreign-friendly, leading up to the implementation of a national sales tax last year that removes a significant load of red tape from international companies wanting to do business in India. And there is an increasing number of such companies, including some of the world’s largest multinationals looking to reconfigure their global supply chains away from dependence on China.

Those are the policies that make India a welcome guest at the World Economic Forum in Davos every year. Back home, though, Modi is seen by many critics as steadily eroding India’s democratic foundations and pursuing ethno-nationalist policies in favor of the country’s Hindus, who represent about 80 percent of the total population. An example of this was seen last week with the opening of the Ram Mandir shrine in Ayodhya, a Hindu temple on the site of a destroyed Islamic mosque in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Modi used the occasion, bitterly protested by India’s Muslims, to announce a new era for India as a global power and challenger to China for economic pre-eminence in Asia.

India’s accomplishments have indeed been impressive, and so far Davos man and Hindu nationalists have been able to coexist peaceably. But, as is the case in many other parts of the world, domestic unrest and heavy-handed political partisanship have the potential to undermine the positive narrative. It’s worth noting that much of India’s economic engine is located in the southern regions of the country, while the center of Hindu nationalism is in the north.

At the same time, it is far too early to write off China as a twenty-first century incarnation of Japan, the economic sad sack of the last twenty years. Amid all the negative China data late last year came word that the country’s largest electric car manufacturer, BYD, topped Tesla for the number of EVs sold in the fourth quarter. The Asia story is far from over, and it promises to be one of the interesting ones in the months and years ahead.