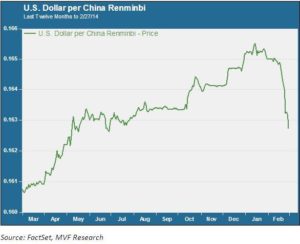

China’s currency, the renminbi (RMB), has a relatively brief history as an asset that rises and falls according to market supply and demand. Up until 2005, the renminbi’s rate was tightly pegged to the U.S. dollar. China’s economic policymakers then began a series of gradual moves to liberalize the currency, albeit with the heavy hand of the People’s Bank of China (PBoC, the country’s central bank) guiding the pace of change. Since then, the renminbi’s trajectory has been a virtual one-way street, appreciating to record highs (both nominal and real) in January 2014. Investors have poured into the market in droves, seeing little risk in the orderly evolution from backwater currency to legitimate contender for reserve status alongside the U.S. dollar and the Euro.

But those bets have been thrown for a loop in the past two weeks. The renminbi has indeed been a one-way street since then – but in the other direction. The magnitude of the drop since mid-February is more than 1.5%.

Please See Yourselves Out…

On the surface, this chart would appear to be little different from other emerging markets currencies that have been hit hard recently, from the Turkish lira to the South African rand and, more recently, the Ukrainian hryvnia. But in China’s case this is not about fickle foreign investors racing for the exit doors; it’s actually about the PBoC itself trying to push those investors out the exit doors. China’s central bank is by far the largest player in the RMB market, and it is the driving force behind the plunge seen in the above chart. Central bankers are not coy about this: since the New Year, the PBoC has stated openly its intention to make the currency “more volatile” – i.e. as likely to fall as it is to rise – in efforts to cool off the pace of capital flows into the country and rid investors of the one-way street illusion.

Not the BOJ Playbook

Why would China want to drive down the value of its currency? Observers familiar with the dynamics of export-centric Asian economies may point to other regional examples, notably the Bank of Japan. Over the course of the last twelve months, Japanese financial policymakers have moved aggressively to weaken the yen, which has fallen more than 12% over that time period. Using a weaker currency to promote trade is a longstanding practice. It would seem to make sense for an economy like China, which derives over 40% of its GDP from international trade, to do likewise. But the People’s Bank of China is not the Bank of Japan. At no time since it became a global economic power has China explicitly sought to devalue the RMB to gain export share. On the contrary, the official policy for most of the time since the partial liberalization in 2005 has been to guide its value upwards.

Cooling Off The Hot Money

China’s economic policymakers have targeted the country’s overheated financial sector as a major structural challenge. The country’s GDP is heavily lopsided in favor of investments, at the expense of domestic consumption. On a national balance sheet “investments” can mean anything from factories manufacturing iPad components to real estate speculation on shopping malls in Guangdong. Speculative ventures have been in favor as of late, many of them funded by capital inflows from Chinese-owned offshore facilities in Hong Kong. Worries of a credit bubble have been hanging over China for some time now. A more aggressive PBoC position in the currency market may be a sign that the government is making good on the policy changes addressed in last November’s Third Plenum.

Investors will be watching closely over the next several days to see if the sell-off continues. Many will be hoping that the currency stabilizes around current levels. There are hundreds of billions of dollars tied up in complex currency derivatives that could unravel if the rate goes much lower. The PBoC understands this, of course, and most likely does not want the currency’s trajectory to spiral out of control. But the unexpected can happen, even in a highly controlled market like the RMB.