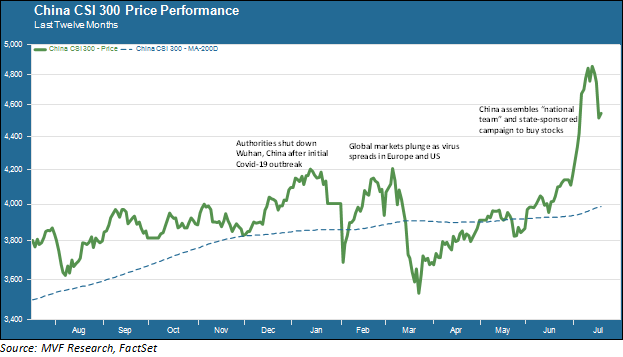

What is a more powerful mover of markets: a home-grown virulent health pandemic or a state-sponsored campaign to buy stocks? Judging from the evidence thus far in China, the SARS-Cov-2 virus would seem to have nothing on the power of the People’s Liberation Daily as a directional force for domestic equity markets. In late June Chinese financial authorities began a renewed effort to bring together the so-called “national team” of banks, brokerages and other financial institutions to support a national campaign in support of the stock market. A week later began the exhortations to the common citizenry via popular national media outlets to show their patriotism by opening bank accounts. As the chart below shows, the national campaign accomplished more on the upside in the space of two weeks than either of the two coronavirus-related pullbacks managed on the downside in late January and mid-March.

Been There, Seen That

Given the extent to which global stock and bond markets suffered when the full force of the pandemic hit in mid-March, it is perhaps surprising that the initial downside in China, in the second half of January after the authorities had effectively shut down the entire city of Wuhan, was limited to a 12 percent pullback in the CSI 300, a benchmark equity index. The index had fully recovered by the time global markets turned down in March. Even during this second reversal the CSI 300 only lost about half as much – 16 percent – as the S&P 500 or key European indexes.

Meanwhile, outside observers monitoring the pace of recovery in China noted a surprisingly brisk pickup in key indicators like industrial production and fixed asset investment. While China’s GDP fell by 6.8 percent in the first quarter, reflecting the shutdown in Wuhan and then nationwide, a ferocious effort to reopen factories and scale up production led to a second-quarter GDP increase of 3.2 percent. But none of this should really have come as any surprise, because this playbook is as old as the China growth story itself. Almost all the post-pandemic growth came from the state via state-owned enterprises. Private sector investment was tepid, retail sales were down by double digits and the number of empty apartments from grandiose construction schemes (estimated to be about 65 million) increased from new municipal debt-funded projects.

Shades of 2015

All of which brings us back to the state and the market. There seems to be a strange ideology baked into China’s economic planning which goes like this: We need to rebalance the economy away from bridges to nowhere and sprawling fields of unoccupied apartments. Let’s get people to buy stocks and have the “national team” (the banks etc.) goose up the indexes. Then the people will take their capital gains, go out and spend money – voila! Consumer spending goes up as a percentage of GDP and the virtuous wheel turns.

This happened in 2015, during another period of wheel-spinning for the economic mandarins in their rebalancing quest. For awhile it worked: the CSI 300 soared by 106 percent from late November 2014 to mid-June 2015. Then it all went south. The index lost about 45 percent from that June 2015 peak to February of the following year. It was dramatic enough to engender stock market corrections around the globe, with the S&P 500 experiencing two pullbacks of more than 10 percent in August 2015 and January 2016. As you can see in the chart above, Chinese stocks had a large downside day this week to suggest that all may not be going according to plan in the latest bout of market propaganda.

Beware the Visible Hand

Most people who pay some attention to economics have a basic understanding of the “invisible hand” – the metaphor used by Adam Smith to explain the benefits of letting the market do its thing while the heavy hand of government stays to the side. China is perhaps the diametric opposite of the invisible hand – a very heavy and visible presence constantly intervening to push the economy towards preordained objectives. But elsewhere in the world as well, the free market is at risk of becoming as quaint as the florid 18th century language of Adam Smith’s writings. Central bank intervention in asset markets is something now taken for granted in the US, Europe and Japan. “No asset left behind” is a more apt description of modern financial markets than the old maxim of “let the market set the price.”

It seems to work, at least in the short term. Stock markets and bond risk spreads seem impervious to just about anything happening in the world around them, secure in the belief that the Fed or the ECB or the Bank of Japan will be there to socialize the losses when need be. But the heavy hand of the state is no guarantee. China’s stock market still hasn’t regained the high point of June 2015. Japan remains far away from the 1989 peak at the height of its asset bubble. The history of market cycles tends to have a common theme: things work great, until they don’t.