Pick a number, any number. That was, more or less, how Fed chairman Jay Powell responded to a question posed by a journalist in this week’s post-FOMC press conference about the current state of the labor market. Specifically, the journalist was asking about the breakeven rate – the number of jobs employers have to create every month to keep the unemployment rate from going up as new job seekers come into the market.

NFP Roulette

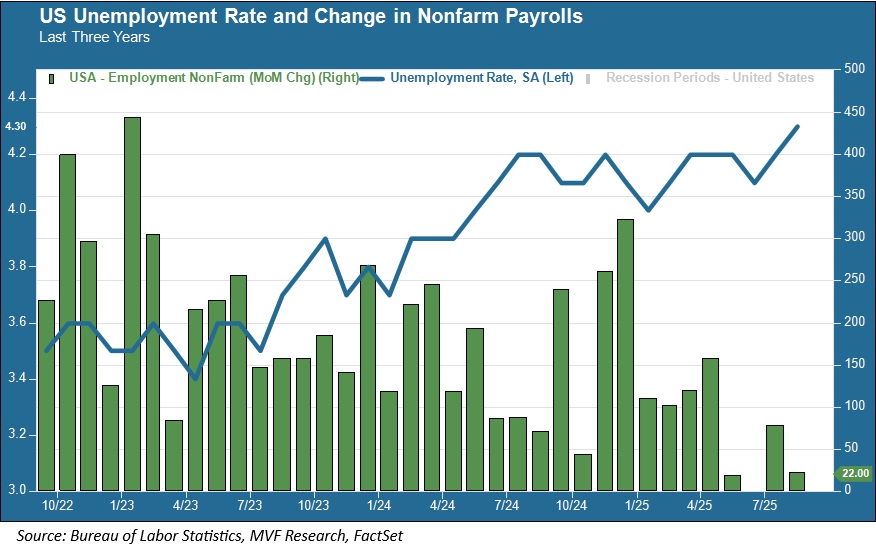

“If you said between zero and 50,000 you’d be right” was Powell’s wry response to the question, referring to the quantity of nonfarm payroll (NFP) gains needed. Meaning: it’s really anybody’s guess what that breakeven number is, because the jobs market today is full of confusion and misdirection. The unemployment rate is rising and NFP gains have declined significantly from their levels a few years ago. The chart below illustrates this trend.

It is clear from this chart that the demand for labor is cooling: the monthly change in nonfarm payrolls is well below where it was a couple years ago, and the latest revisions showed that the number actually declined for the month of June. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate has ticked up, slowly but steadily, to its highest level since the immediate aftermath of the pandemic in 2020-21. Now, while the latest NFP number of 22,000 payroll gains technically falls within that “zero to 50K” quip of Powell, it would seem to be coming in somewhere short of the breakeven rate. Anecdotal evidence suggests that demand for labor is weakening in just about every sector of the economy except for healthcare. Manufacturing employment, to name one, is down by 78,000 for the year to date. Other areas including retail, professional and business services, construction and hospitality have shown little change in this period. And conditions are particularly tough for younger job seekers, especially – in a striking reversal from the normal trend – for young college graduates.

The Supply Side

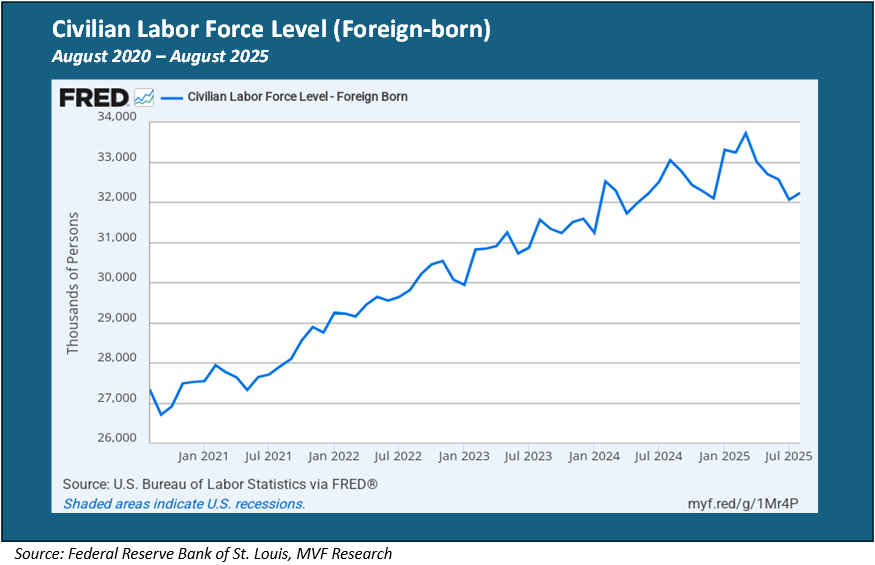

But the jobs numbers don’t just reflect the demand side. At the same time as demand has been weakening, so is supply. As Powell noted during Wednesday’s press conference, a big impact on the supply side has been immigration policy restricting the flow of new workers. Think again about the logic behind the breakeven rate. How many new jobs have to be created to keep unemployment in check depends on how many people are out there looking for jobs. If the number of new job seekers is lower, then the breakeven rate is also likely to be lower.

We know that the number of foreign-born workers – whether due to deportation or just not wanting to risk showing up at the local Home Depot parking lot in search of work – has declined significantly since the beginning of the year. As the chart below shows, that number fell from around 33.3 million in January to about 32.2 million in August.

So how bad are things, really, in the labor market? Nobody really knows, including the Fed, and that is why Powell described the 0.25 percent cut in the target Fed funds rate announced Wednesday as a “risk management” cut, rather than signaling a clear and decisive move towards monetary easing. An unemployment rate of 4.3 percent, where it stands today, is not unusually high – in fact, it is not too far away from what economists in the past have tended to regard as the “natural” rate of unemployment under conditions of economic stability. But the trend is in the wrong direction.

By referring to this rate cut as an exercise in risk management, Powell addressed both sides of the Fed’s dual mandate: taking steps to prevent unemployment from getting uncomfortably higher while at the same time acknowledging that the battle against inflation is far from over. The high degree of uncertainty in the economy makes it difficult to chart a clear path forward. Look no further than the Summary Economic Projections – the “dot plots” – that accompanied this week’s FOMC decision. One of the nineteen “dots” in the Fed funds rate projections for the rest of 2025 actually contemplated a rate hike before the end of the year, while another dot reflected expectations for five more rate cuts (the less said about that latter projection, the better). The truth is probably somewhere in between. Pick a number, any number.