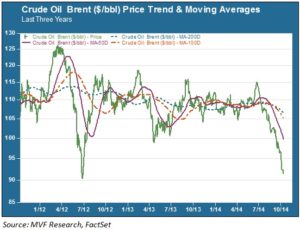

Volatility is back in risk asset markets, at least for the time being. There is no one single factor to explain the wild intraday gyrations in major stock indexes, all of which are experiencing a pullback of varying magnitudes from their high water marks. Europe’s economic woes, growing fears about the spread of Ebola and the usual geopolitical flash points all figure into the mix. But one market that is now solidly in bear county is crude oil. Brent crude, a key benchmark oil futures contract, has fallen from a late June peak of $115 to just over $90 as of yesterday’s close. That’s a fall of more than 20% and, as the chart below shows, its lowest level in more than three years.

Shale Fever: The Supply Equation

Oil prices, like any commodity, are driven by supply and demand. Arguably the biggest development on the supply side is the dramatic increase in U.S. domestic oil production, fueled by the boom in shale oil extraction. Domestic production is estimated to be around 8.9 million barrels a day (mm/bbd), an output level very close to that of longstanding production king Saudi Arabia. Imports now account for just 14% of our total oil consumption, down from about 60% in 2005. As U.S. demand for imported oil has slowed, foreign producers have had to find other markets. OPEC countries, Russia and Latin American producers are furiously competing with each other for market share. That means cutting prices; the OPEC cartel’s storied ability to micromanage and dictate world crude prices is a long distant memory.

Sluggish in Shanghai: The Demand Equation

Unfortunately for the oil producers, their attempts to increase share in non-U.S. consumer markets come at a time when demand is sluggish. GDP growth is flat or negative in Europe and Japan, and slow relative to historical norms in China, the most important market for most major commodities. Analysts estimate that 1Q 2015 global demand for OPEC oil reflects about a 2.5 mm/bbd surplus from the cartel’s current production levels. Last week Saudi Arabia lowered its official prices to key Asian customers. Fears of continuing price wars are weighing heavily on the prices of oil producer stocks, which are strongly underperforming the broader equity market.

This Too Will Pass

As dire as conditions look at present, they cannot last forever. The profitability of oil production is directly linked to the price at which it can be sold. Consider the U.S. shale oil boom. Extracting oil from shale formations requires nontraditional techniques, such as horizontal drilling, which are costlier than drilling in conventional wells. If oil prices fall much further, fewer producers will keep drilling. That will reduce supply, which in turn will impel prices higher. And OPEC, despite its reduced leverage today on world markets compared to the salad days of the 1970s, is still able to coordinate and reduce output if price levels get too extreme. We’re not likely to see a return to $50/bbl oil. But prices may have a hard time breaking out too much above $100 for sustained periods of time.

Oh, and how is this all affecting prices at the pump? By less than you might think: average gas prices in the U.S. have fallen about 11% since their June peaks, and much of that is seasonal. Refining and distribution economics are entirely different from exploration and production, giving us less relief at the pump than we would want.