It would appear that the Twitter-dominated world in which we live is incapable of existing anywhere below the level of five-alarm panic for any meaningful period of time. In actual fact, global economic growth has not been laid waste by the ravages of the trade war now well into its second year, but that minor bit of empirical evidence has not stopped the daily churn of angst-filled headlines. But the Twitterverse also sustains itself through the constant ingestion of the shiny and new. Cue up the newest discussion morsel for the uproar and consternation of the financial chattering class – the prospect of an imminent currency war led by the US dollar. Is this a real threat, as a growing number of industry pros are telling us? Is it even possible to wage a currency war on behalf of the world’s reserve currency? Let’s consider the evidence.

Strong Dollar Blues

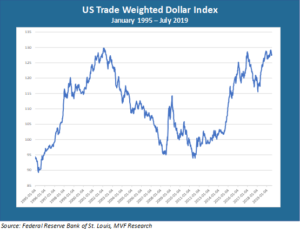

The US dollar is in a position of strength – that much is indisputable. The chart below shows the long-term trend (going back to 1995) for the US trade weighted dollar index. This shows the performance of the greenback versus a basket of 26 foreign currencies with whom the US engages in bilateral trade. As the chart shows, the dollar is currently close to its quarter-century high point reached in the early 2000s.

For most of the time shown in this chart, there has been very little in the way of coordinated currency intervention involving the US dollar. The big trend movements you see in the chart derive mostly from organic economic trends, including the ballooning trade deficits of the mid-2000s that significantly weakened the dollar, and then the embrace of hyper-aggressive monetary stimulus by the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan earlier this decade, pushing interest rates below zero in those markets and making dollar-denominated assets a more attractive alternative. In terms of short-term trading movements, the dollar has tended to be viewed as a safe haven currency during periods of heightened economic uncertainty, while losing value against the likes of the euro or the Chinese renminbi during more robust spurts of global growth.

In simplistic terms, economic policymakers tend to see a strong national currency as an impediment to growth as it negatively affects the competitiveness of exports. This is the argument you hear from those in the current US administration pushing for intervention. This rhetoric goes hand in glove with the persistent attempts of this administration to jawbone the Fed into lowering interest rates. Indeed, a number of professional observers worry that an aggressive Fed move on rates later this month (the odds of which have gone up yet again after some super-dovish comments by Fed members yesterday) will be seen by the market as the Fed acceding to a push by the Treasury Department to formally intervene in currency markets (Treasury maintains that such a formal program “for the time being” is not on the table).

Be Careful What You Wish For

The relationship between a national currency and domestic economic growth is simple enough in the textbooks, but the real world is a more complex Petri dish of unanticipated consequences. The US certainly does have formal mechanisms in place to launch a currency intervention should it choose. The Exchange Stabilization Fund has been around since 1934, and it is through this mechanism that the Treasury Department could undertake direct market intervention.

But currency intervention is not a one-sided thing. Consider, for example, one of the most prominent historical examples in the post-Bretton Woods era of concerted currency manipulation: the Plaza Accords of 1985. The US and its major economic partners agreed at that time that the US dollar’s strength was an impediment to global growth (the greenback had appreciated against the Deutsche mark by some 90 percent in the five years leading to the Plaza Accords). As a result, the action taken by the Reagan Treasury Department to bring down the value of the dollar was supported by the monetary authorities of Japan, West Germany and elsewhere to support their own currencies).

It is very unlikely that today’s policymakers in Brussels or Tokyo or Beijing would line up on the same side of the argument as Trump and Mnuchin to carry out some modern reprise of the Plaza Accords. More likely, a US-driven currency war would lead to a destructive race to the bottom as all players sought to shore up their own domestic competitiveness.

The result of which, very plausibly, would be an ever-greater level of economic uncertainty and a higher likelihood of falling growth or global recession. In other words, an environment that would be seen by the market as decidedly “risk-off,” raising the attractiveness of traditional risk-off assets. Like, oh, just to name one, the US dollar. Yes, a currency war could wind up delivering the opposite of what its backers wanted.

Now, we don’t think a currency war is going to happen – if the trade war is any example, then this would likely be 90 parts Twitter braggadocio and 10 parts substance. But the risk is not zero, so sadly, as always, attention must be paid.