The debt ceiling is the financial markets equivalent of the Night of the Living Dead – a zombified relic of some ill-conceived legislation from long ago that lies dormant until Congress has to start talking about it again, at which point it rises and stalks the earth until some brave posse of bipartisan stalwarts – hopefully – put it back in the ground with a continuing resolution or a temporary spending measure or some other means of deferring the problem to another day.

The creature is alive once more, and nerves may be on edge for some time between now and midsummer. The idea of the US government defaulting on its debt – literally by refusing to pay for obligations it has already incurred – should be preposterous. But one-year US credit default swaps, which represent the price of insuring against a sovereign default, are trading at a level of 106 basis points, up from 15 basis points at the start of the year and the highest level since at lest 2008. If you want a contextual picture of what that means, the current credit default swap rate for Greece’s sovereign debt is 46. Now, the one-year CDS market is not particularly liquid, so one should not read too much into it – but anecdotally at least it’s a bit odd that investors currently peg the likelihood of a US default at more than twice the level of that of Greece. Are they really going to go over the edge this time?

The 2011 Playbook

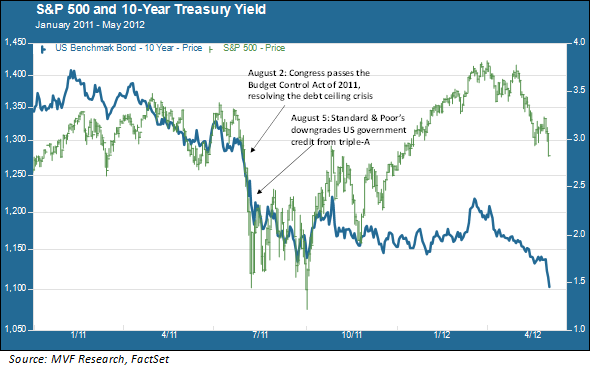

Nobody can predict what the outcome of the current standoff between the Republican House of Representatives and the White House will be (other than the fairly obvious fact that the bill passed by the House earlier this week will go nowhere). But it’s worth taking a look at what happened in financial markets the last time the debt ceiling zombie came close to a scorched-earth outcome, in 2011.

As the chart shows, the 2011 debt ceiling debacle created a considerable amount of volatility in both the stock market and the bond market – and the volatility continued for several months after Congress and the White House narrowly avoided default with the passage of the Budget Control Act on August 2 (followed almost immediately by the S&P downgrade of US Treasuries from triple-A status). The magnitude of loss for the S&P 500 from top to bottom was around 19 percent (the market had fully recovered its losses from the July 2011 peak by February 2012, however). The terms and conditions of the Budget Control Act, unfortunately for anyone wanting some financial market stability, would require then-President Obama to formally request additional debt ceiling increases twice more – in October 2011 and January 2012 – which at least partly explains why markets remained on edge for so long after the bill’s initial passage (on a side note, it is worth considering that the 10-year Treasury yield actually went down, and mostly kept going down, after the S&P downgrade).

Committees to Save the World

So what should we expect this time? Not surprisingly, we have received a fair number of inquiries about this in recent days. One thing that deeply concerns many observers is that the partisan divide is substantially wider and more hostile today than it was in 2011 (and it wasn’t exactly all sweetness and light back then, either). Political folks run the numbers and come up with plausible cases to make that both Republicans and Democrats could talk themselves into short-term advantages from letting the ship go over the edge this time (the advantage coming, cynically, from “winning” the ensuing blame game).

But that is not how these things normally pan out. One thing we have learned over the years – going all the way back to events like the bailout of the hedge fund Long Term Credit Bank in 1998 – is that any crisis with the potential to inflict structural devastation onto financial markets begets an ad hoc Committee to Save the World, which one way or another figures out how to defuse the crisis. We expect that, if political brinksmanship pushes us close to that event horizon of outright default, some assortment of sober-thinking individuals from the Fed, Treasury, White House, Congress and wherever else will come up with something that solves the immediate problem.

We don’t say this with one-hundred percent certainty, because there is no such thing. In the world of risk assessment you are always dealing with probabilities. If the probability of one outcome – a short-term solution – is vastly higher than the probability of another – a sovereign default that lays waste to the entire spectrum of financial assets – then stockpiling cash in anticipation of the low-probability event is a bad idea. Long-term portfolio performance requires the discipline not to flinch when short-term conditions appear volatile. We will continue to share our thoughts on this as the situation evolves in the coming weeks.