At the end of last month a Chinese company called Didi Chuxing went public via an initial public offering of American Depositary Receipts (ADRs) on the New York Stock Exchange. The $4.4 billion raised made Didi, a ride-hailing app, one of the most prominent of the 34 Chinese companies that raised money via New York-listed ADR offerings in the first half of 2021.

Didi was in many ways a paragon of the China narrative that has increasingly captured the fancy of global investors. A plucky start-up founded ten years ago by an ex-executive of Alibaba, the sprawling Internet colossus, Didi gained a foothold in the competitive urban transportation market by appealing to a younger, tech-savvy clientele and making some smart strategic alliances. Didi Dache – literally “Didi honk honk” – as it was known then, attracted the deep pockets of regional venture investors including Softbank and Tencent as it solidified a near-monopoly on ride-hailing services in major metropolitan areas.

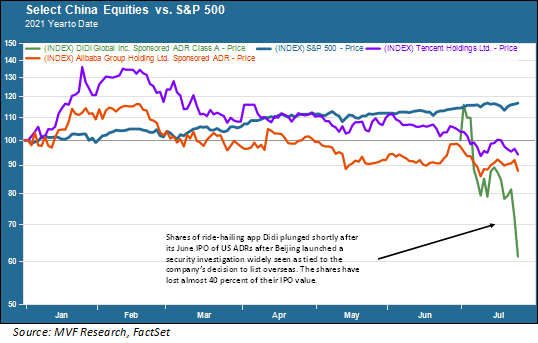

Not to put too fine a point on it, things did not go well for IPO investors. The chart below shows the performance of Didi from the June 30 IPO. For comparison the chart also shows two bellwether Chinese firms – Alibaba and Tencent – and the considerably less volatile S&P 500.

CAC Attack

Prospective investors in the Didi IPO might have asked a couple questions before they took the plunge in a company that has subsequently lost almost 40 percent of its value from the IPO pricing. Why, for example, were more than two thirds of all those Chinese IPOs in the first half of the year trading below their offering prices? Was something going on behind the scenes that the interested parties – namely the selling shareholders like Softbank and their fee-besotted investment bankers from the Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs et al – were trying to keep under wraps?

Well yes, as it turns out, there was. The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), a technology watchdog, has been busy at work for much of this year launching investigations into technology-based companies with overseas stock listings. The CAC’s heavy hand is quite a bit more than the politically-motivated machinations that led to the cancellation of the Ant Group IPO last November. It concerns data security and the potential for improper (in China’s view) release of customer information into foreign entities (the idea of tons of data about individual Chinese users of Didi’s services floating around the predictive analytical platforms of Google or Facebook would give Beijing regulators nightmares). Just as Didi’s IPO came to market the CAC announced a formal investigation, intimating that the company was in violation of data privacy and national security laws. Oops.

The Dilemma

We used the word “dilemma” in the title of this article, but have not yet spelled out exactly what the dilemma is. We used the story of Didi Chuxing to illustrate a trend that is likely to continue in force: the decoupling of Chinese equities from overseas (especially US) securities exchanges. In the wake of Didi, many of the companies that had filed for a New York listing later this year are redirecting their sales to Hong Kong. The island territory has a deep financial infrastructure going back to well before it became part of China in 1997. The recent aggressive moves by mainland China to quash the “one country two systems” framework of the 1997 handover ensures that Hong Kong’s securities markets will function within the edicts of what Beijing deems acceptable, including standards of disclosure providing no more transparency than what Xi Jinping’s regime will allow.

If China’s own authorities want fewer overseas listings, they are joined by many of their counterparts here at home. In the past couple years US securities regulators, backed by many China hawks in Congress, have pushed for greater disclosure of domestic financial information by Chinese companies applying for a listing. Earlier this year three companies, including communications giant China Telecom, were booted off the NYSE in conjunction with their perceived ties to Chinese military agencies (as if to say “so what?” China Telecom recently completed a $8.4 billion secondary share offering on the Shanghai exchange).

The dilemma is this. On the one hand, investors are increasingly eager for exposure to the world’s second-largest economy, with some of the most innovative global competitors in leading-edge industry sectors. On the other hand, it is increasingly clear that taking on such exposure comes with a cost: the cost of lower-quality standards of transparency that are likely to become even more obscure as companies relocate out of the US, and the cost of heavy-handed regulation that could impede the ability of these companies to freely innovate and operate in markets around the world.

There is no easy answer to the dilemma. We face it ourselves every day, as we make decisions about what is in the best long-term financial interests of our clients. As much as we would prefer that the worlds of rational investing and global politics never intersect, we are all too aware that they do – and will most likely continue to challenge our investment decision-making. A great deal hangs in the balance of the deterioration of relations between the world’s number one and number two.