One of the big stories in markets this year has been the hale performance of Japanese equities, with the benchmark Nikkei 225 index finally clawing back to and surpassing the record high it had set 34 years earlier, at the end of calendar year 1989. Currently the Nikkei is up 13.2 percent for the year – not bad! But that’s 13.2 percent in local currency terms. Unfortunately for investors whose portfolios are calculated in US dollars, the Japanese yen is down around ten percent versus the greenback. So that nice gain on Japanese stocks winds up as a fairly anemic low-single digits return when it shows up on your dollar-denominated quarterly statement.

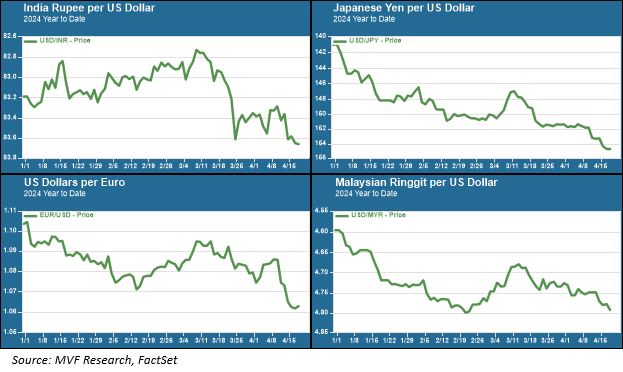

And it’s not just Japan. Currencies everywhere, across the spectrum of developed and emerging economies, are down against the dollar this year, and that trend has accelerated in recent weeks.

Higher For Longer

The strong dollar is a direct outcome of the market’s long-overdue realization that US interest rates are likely to stay higher for longer, with doubts now growing that the Fed will cut rates at all. “America’s interest rates are unlikely to fall this year” ran a headline in the Economist magazine this week, which sums up the sea change in conventional wisdom about rates from the euphoria that prevailed at the end of last year. Three successive readings of hotter than expected inflation put paid to that short-lived era of good feelings (it also validates what Fed chair Jay Powell said at the post-FOMC meeting press conference in early February about the Fed not yet being convinced by the data that the inflation dragon was slain). Higher interest rates attract more foreign money into dollar-denominated securities.

Not only are US rates likely to stay high relative to other countries; the US economy is also growing faster. This week the IMF raised its estimate for real US GDP growth in 2024 to 2.7 percent, which follows a much stronger than expected growth rate of 3.1 percent last year. Other economies fare less well in the IMF’s reckoning, with Germany expected to grow just 0.2 percent, Great Britain at 0.5 percent and Japan at 0.9 percent. Put together, the combination of higher interest rates and a stronger economy is amplifying concerns among policymakers elsewhere in the world that their currencies have further to fall.

Remembering 1997

These concerns came to light this week as the mandarins of monetary policy gathered in Washington for the Spring Meetings of the World Bank and IMF. In a rare joint statement, the finance ministers of Japan and South Korea joined US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to express “serious concerns” about the recent sharp falls in their respective currencies, the yen and the won, against the dollar. That statement provided at least a bit of relief in currency markets, as Asian currencies gained a little ground. For the finance ministers the concerns are well-founded. In the summer of 1997 a sudden and sharp devaluation hit Asian markets from South Korea to Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. Portfolio managers had poured billions into these “Asian tiger” markets earlier in the decade, but fears that the economies had gotten too far ahead of themselves sparked a panicked rush for the exits and a period of painful adjustment for the countries in question.

To be sure, we do not foresee a repeat of the 1997 crisis. Central banks are much better-positioned today in their foreign exchange reserves than they were back then. And there are benefits to a weaker currency for countries with a high reliance on exports for growth, which includes much of the Asia Pacific region. But instability can beget more instability, which is why Yellen and her Japanese and Korean counterparts took pains to issue that joint declaration in support of restoring currency stability. We will see in the days ahead what the central banks will do if jawboning on the sidelines of an international conference does not stop the selling.