The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is a theory about asset prices and information. At the heart of this theory is the assertion that capital markets are fully efficient. According to the EMH, asset prices always reflect every single piece of information that could reasonably impact the asset’s value. As new information becomes known it is instantaneously baked into the price. Anyone operating at a speed slower than Planck time could not possibly take advantage of such new information to trade profitably. Price always equals value, the market is always rational, and bubbles don’t exist, say the efficient market proponents.

Theater of the Irrational

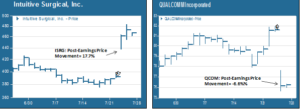

The problem with believing in the Efficient Market Hypothesis is that every fiscal quarter delivers a compelling piece of evidence to the contrary, otherwise known as corporate earnings season. The quirky rituals of earnings season refute two key EMH tenets. First, the idea that an asset’s price is always equal to its value is very hard to square with the fact that prices can lurch up or down in double digits before, during and after earnings announcements. Second, the way that prices move in reaction to the actual information released tend to be anything but rational. Consider the following chart, which shows the price movements of two companies – Intuitive Surgical and Qualcomm – in the period leading up to and immediately after their respective second quarter earnings announcements:

Surprise, Surprise

What could possibly have happened to make Intuitive Surgical a more valuable company by 17.7% in just one day? Did the net present value of Qualcomm’s future free cash flows suddenly drop by 7%? Of course not. Large publicly traded companies like ISRG and QCOM continually issue guidance on their projected sales, earnings and other key data. Analysts use this forward guidance, as it is called, to model their valuation estimates. Going into earnings season there are consensus estimates for just about every company in the S&P 500. When the actual numbers are released they are compared to the earlier estimates. If the actual figures are higher than the estimates then we have a “positive surprise” or “beat”, in analyst-speak. Lower than expected results, by comparison, are “misses”. High-profile companies can generate considerable drama around their earnings announcements, and the drama often leads to these erratic – and very un-EMH – price movements.

The Fool’s Errand

But the EMH does get one thing right: attempting to profit from a company’s earnings announcement is a fool’s errand indeed. Consider again the two companies in the above chart. You would think that Intuitive Surgical had a blockbuster quarter, and that something awful must have happened to Qualcomm, right? Wrong on both counts. ISRG’s earnings were actually 3.5% lower than the consensus estimate based on the company’s earlier guidance. Qualcomm, on the other hand, delivered earnings 18.6% higher than the estimate. The ensuing price movements are basically the opposite of what a rational investor may have expected.

Markets defy rational expectations every day. Those who come into the capital markets with rigid ideological views about how assets ought to behave should expect to be disabused of their dogma in very short order. Smart investing requires an openness to all ideas and all possibilities, while knowing that no one single view or theory works in all markets at all times.