There have been a couple different stories about corporate earnings out there in the mediasphere this week. You probably know one of them, especially if you yourself happen to own shares of Netflix, which are worth quite a bit less at the end of the week than they were on Monday morning. You may not have heard the other story, though, which is that with a little over 100 S&P 500 companies having reported so far their first quarter results, the consensus estimate for earnings per share growth for the quarter is now 6.6 percent, up from 4.5 percent just three weeks ago.

In other words, conditions seem to be improving for companies’ financial performance despite all the headwinds out there – inflation, rising interest rates, the war in Ukraine, Covid lockdown in China and so on ad nauseum. And yet there is an asterisk to that improved performance trend, and this week the asterisk came in the form of a 63 percent freefall in the price of one of the most high-flying stocks of the last 12 years. Let’s look more closely at both these stories.

Maintaining the Margins

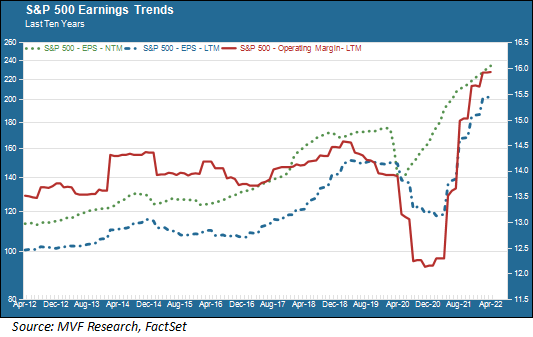

The big question for analysts covering US publicly traded companies has been whether they would be able to sustain their recent strength in operating profitability given the higher cost of many inputs – raw materials and labor chief among them – as well as the supply chain problems resulting in backlogs and sky-high transportation costs. The answer, so far anyway, seems to be yes. The chart below shows the trend in operating margins (operating income as a percentage of sales), along with trailing and forward earnings per share, for the past ten years.

Operating margins (the crimson line) remain at a ten-year high, which in turn means that companies are able to pass on cost increases to their customers, which in turn also helps their bottom line earnings grow (the blue line in the above chart represents earnings per share for the last twelve months, while the green line indicates earnings estimates for the next twelve months). The key driver sustaining this profitability is the ongoing level of above-average demand from American consumers, who continue in the aggregate to be spending ferociously.

The improved profitability outlook would seem to be good news for anyone worried about an impending recession; after all, if companies are selling, people are spending and jobs are there for the taking, that would seem to put the likelihood of negative GDP growth to be very low indeed. This brings us to Netflix, to ask whether this is the figurative canary in the coal mine warning of danger ahead.

Streaming to a Trickle

The Netflix earnings call this past Tuesday was one of the all-time lulus of a surprise. Analysts had been expecting the company to report somewhere in the neighborhood of 2.5 million new subscribers; instead, the streaming giant announced an outright decline of 200,000 subs, the first quarterly decline in a decade. Management was pretty forthright about the key reasons for this performance, including increased competition, password sharing among households and new ways content consumers are configuring their viewing experiences. These are fundamental forces that will be affecting anyone competing in the already-crowded streaming space (fittingly, this was also the week when Warner Bros. Discovery announced it would be shutting down the new CNN+ streaming service after just one dismal month).

Left unsaid was a bigger question: are the lower subscriber numbers at Netflix a sign that households are starting to pare back on discretionary spending choices, as a result of the pressure inflation is putting on their monthly budgets? We don’t have a definitive answer to this yet; this is just one data point representing one quarter’s worth of activity. But it may be a preview of what we start to see if inflationary expectations become more entrenched into real-world behavior. We think the market probably overreacted to the actual news from the Tuesday Netflix call. But it’s what we don’t know that could be the thornier issue down the road.