Emerging market (EM) equities have long enjoyed a position as a core strategic asset class for diversified long term investment portfolios. Using the traditional tools of modern portfolio theory (MPT), investment advisors place EM assets in the high growth / high risk portion of the allocation pie: delivering outsize gains in the long run but not without some significant bumps along the way.

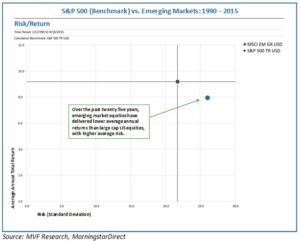

A look back at the last quarter century of emerging markets, however, calls this approach into question. Consider the chart below, showing the risk/return characteristics of the MSCI Emerging Markets index versus those of the S&P 500 from 1990 to the present.

Over this time period the S&P 500, a key benchmark for large cap US equities, delivered annual average total returns of 9.2 percent, while emerging markets as measured by the MSCI index produced average annual total returns of just 7.9 percent. Moreover, the outperformance of US equities came with lower risk: 21.7 percent standard deviation versus 26.0 percent for emerging markets. Now, there have been periods within this twenty five year window when EM stocks have done quite well. Given the overall performance though – and particularly within the context of today’s global economy – investors would be well served to think carefully about future allocations. Should emerging markets be considered a default asset class, or are they better as a periodic tactical option?

Good Times, Bad Times

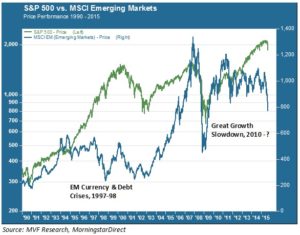

Emerging markets did not escape the seismic market disruptions of the past quarter century, tumbling lower in the downdraft of the tech bubble collapse in the early 2000s and then freefalling during the 2008-09 market crash. But, while they felt the pain when developed markets fell, they didn’t always share in the gains when the US and other markets rallied. The following chart shows the price performance trends for US and EM equities over this time period, illustrating clearly where key trend divergences have occurred.

The first major trend divergence occurred during the spate of currency and debt crises that began when the Thai baht’s devaluation in 1997 triggered a landslide of Asian currency retreats, and continued with the Russian debt default in 1998. Unfortunately for EMs, these problems happened while the world economy was booming and US markets in particular were enjoying the fruits of the Internet’s ascendance. The S&P 500’s 19 percent pullback in August 1998, at the peak of Russia’s woes and the related collapse of hedge fund Long Term Capital Management, paled in comparison to the 65 percent-plus freefall the MSCI EM index suffered from October ’97 to November ’98.

Of course, the misery of the late 1990s receded in the rearview mirror as the stunning rise of China as a global economic power led the EM asset class to vastly outperform just about everything else in the middle of the 2000s. As with the dot-com collapse, though, EMs found themselves suffering from problems that originated elsewhere as markets headed south in 2008. The subprime loan crisis that begat the Great Recession was a home-grown American problem, yet the peak-to-trough drawdown was far more severe for emerging markets than for US equities. This again illustrates an uncomfortable risk asymmetry. Emerging markets are vulnerable to the flu when developed markets catch cold. But the severe illnesses which periodically befall EMs require little more than a couple Advil to restore US equities to health.

Growth: Gone Today…

Many emerging markets took bold steps after their late ‘90s crises to reform their economies and financial systems, notably by building up significant foreign exchange reserves and shifting the mix of their debt burden to include more local currency financings. These improvements notwithstanding, the EM model is challenged today by the elusiveness of the key ingredient at the heart of that model: growth. The tag line of “growth engine” does not fit well when Brazil and Russia are experiencing sharp reversals, South Africa and Turkey are likewise struggling to find a path back to prosperity, and China’s troubles send shock waves into the capital markets on a near daily basis. The uninspired performance of EM equities from 2010 to the present, as seen in the above chart, is particularly concerning given its coincidence with an era of unprecedentedly low interest rates. Growth markets should be catnip for cheap money – unless, of course, the growth isn’t there.

Here Tomorrow?

Today’s seemingly intractable problems notwithstanding, there are good reasons to not dismiss emerging markets out of hand as a strategic asset class. These countries are for the most part significantly wealthier than they were back in 1990. Although their political and legal systems are a mixed bag, in most cases the systems have produced a better living standard for the citizens of these countries, with investments in infrastructure, housing and domestic enterprises offering even more appealing opportunities for their future generations. It is generally unwise to underestimate the human will to prosper and make a better life for one’s children. A world economy characterized by young, strong growth markets and older, slowing but still rich developed markets certainly cannot be ruled out as a viable scenario. In such an environment emerging markets should plausibly regain momentum.

And that, in our opinion, is how you should answer the question about emerging markets as a strategic asset class: it depends on how you see the world. If you believe that growth will return to the world economy and that EMs will be the engine of that growth, it would be unwise to leave exposure to these markets out of a long term investment strategy. If on the other hand you believe that winter is coming and likely to stay put for a long time, then perhaps it would be wiser to consider other sources of high risk / high return performance. Our views tend towards the former, and we will continue to advise our clients to not abandon EM equities as a core asset class.