The term “emerging markets” came into being way back in the ancient mists of the 1980s, replacing the clunkier “third world” as a descriptor for countries that, while lacking much of the hard and soft infrastructure of the developed world, had a future of bounteous growth prospects with which to lure investors willing to take a bit more short-term risk in a slice of their portfolios in exchange for higher returns in the long run. The concept really gelled into an investment strategy in the early 1990s with a slew of privatizations and overseas securities listings for previously state-owned companies in China.

Back then three parts of the world stood out as the likely growth engines for emerging markets: Asia, including China and so-called “tiger” economies like Taiwan and South Korea; Latin America, led by resource-rich Brazil and US-adjacent Mexico; and a somewhat vaguer mix of Middle Eastern countries and the embryonic capitalist economies of Eastern Europe, tossed together in a salad called “EMEA” (Europe, Middle East and Africa). Actual on-the-ground conditions in each of these regions (indeed, within the regions themselves) differed greatly. Yet during the 1990s the differences got papered over in favor of a simple story: higher growth than the global average, with some potential bumps along the way towards long-run outperformance.

Define “Long Run”

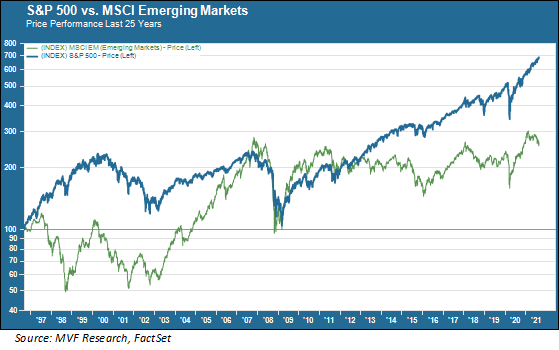

So how has that trade worked out so far? There’s been plenty of risk. The annualized standard deviation for the MSCI Emerging Markets index over the past ten years is 17.8 percent , while that for the MSCI World Index, comprised of 22 developed-market economies, is 13.9 percent. For all that extra risk, things haven’t exactly worked out over the “long-run” as hoped. The chart below shows the performance of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index versus the S&P 500 over the last 25 years.

The numbers on that chart show comparative cumulative percentage price returns over this 25-year period; specifically, that the cumulative return for the S&P 500 was more than twice that of the emerging markets index, despite the considerably lower risk associated with the large-cap companies that populate the S&P 500. Now, you can see that there have been periods where the emerging markets index did extremely well – most conspicuously in the years from 2002-07 that roughly coincided with a great supercycle in industrial and energy commodities markets. Other than for those having a preternatural gift for timing these rare bursts of outperformance, though, this asset class has been distinctly disappointing.

Time to Call It What It Is

That chart will not give much encouragement to anyone wondering if this asset class will ever be worth investing in. For starters, though, it’s really time to stop calling emerging markets an asset class – at least if you want to stick to that three-regions framework that we described above. Whether or not you should invest in “emerging markets” today really comes down to one thing, and that one thing is China.

The MSCI Emerging Markets index today includes 27 countries. China alone, though, makes up just about 35 percent of the index’s market cap. Add Taiwan (which may or may not become an actual part of China sometime in the next several years) and you’re at 50 percent. Add in South Korea and India, the next two biggest holdings, and you’re almost at 75 percent. Everything else – those other 23 countries – add up to just over one-quarter of the index’s value.

“Emerging markets” in this sense really has no unified meaning. It’s China, which as the world’s second-largest economy is a category unto itself. It’s three other Asian markets, two of which (Taiwan and South Korea) are considered by many metrics to already be developed economies. It’s not much else.

As Goes China

So if you are thinking about an “emerging markets” investment, the thing to consider is not how poorly this investment fared over the past quarter-century. It’s how you think China is going to develop in the next five and ten years – and beyond – and whether that development trajectory is going to translate into value for the common equities of Chinese companies. As you know from some of our recent weekly commentaries, this is a burning question in the market today without a clear answer. The era of Chinese internet behemoths like Alibaba and Didi Chuxing, with their US ADR listings, seems to be in eclipse. Just this week China appeared to indicate that it will place outright bans on companies with large amounts of sensitive customer data from any future overseas listings.

That development does not necessarily bode poorly for the broader Chinese market, though. Sectors like semiconductors, biotechnology and green energy are high priority strategic initiatives for Beijing, and that priority will flow into companies that will be available to foreign investors via listings either on local exchanges or, increasingly, via the comparatively sophisticated financial market infrastructure of Hong Kong. The diversion of planned US ADR listings to the Hong Kong alternative is already well underway.

For our part, the only thing of which we feel certain is that there is a great deal of uncertainty about the co-evolution of China’s markets with those of the US, Europe and non-China Asia Pacific in the years ahead. But we also believe that at least a modest exposure to the country that may actually be the world’s largest economy by the middle of the decade is warranted. The next 25 years – for better or for worse – are unlikely to resemble the last 25 years.