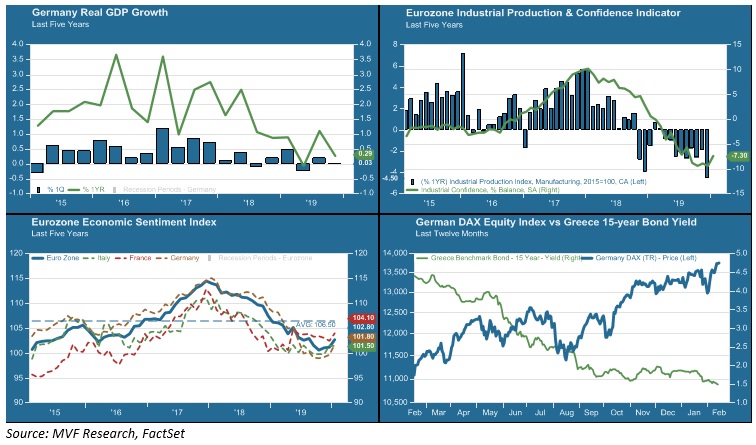

It may be Valentine’s Day, but there’s not much love to be found in recent economic data from the long-suffering Eurozone. Worse still may be in store given the importance of exports to China for Europe’s biggest economies, and the still-unquantifiable toll the coronavirus may have on growth prospects in that country. Yet investors seem perfectly content to keep on keeping on. The chart below presents three key economic indicators for the region along with the performance for the last twelve months of the German DAX equity index and Greece’s 15-year sovereign bond yield.

Stuck In the Mud

Back in 2017 it seemed like Europe was finally shaking off the last of the crisis that threatened the very integrity of the single currency region from 2010 to 2012. “Synchronized growth” was the phrase of the day among the financial chattering class, with the EU joining the US, Japan (remember Abe-nomics?) and emerging markets on a coordinated upswing.

That was then. Since the first half of 2018 Europe has slowly made its way back to the plodding, barely-there growth trends characteristic of the earlier part of the 2010s. Industrial production (the upper right quadrant of the above chart) has plummeted since then. Economic sentiment – a blend of business and consumer confidence – has fallen steadily (lower left chart). A brief uptick in sentiment at the end of last year is unlikely to last given the latest hard data points.

Perhaps the bleakest of those data points is Germany, where GDP growth (upper left chart) is a hair’s breadth away from tipping into recession. The Eurozone’s largest economy derives a significant amount of its overall output from exports of high-value goods to China. Whatever the impact of the coronavirus winds up being on the Chinese economy, that impact will resonate in Germany and quite possibly drag the entire region (France and Italy are also struggling) into recession by the middle of this year.

Bad Is Good

If all that sounds dire, then why have investors pushed Greek sovereign bond yields down to laughably low levels? The lower right chart above shows the 15-year bond currently trading at a 1.5 percent yield. Yields on the 10-year bond fell below 1 percent this week (which would seem to make 10-year US Treasuries, trading around 1.6 percent currently, awfully appetizing). And EU equity markets are blithely powering along in tandem with risk assets in most of the world. Isn’t the prospect of a looming recession supposed to cast a negative pall on markets? In this case apparently not, potentially for two reasons.

The first of those reasons is the euro, which has lost more than 3 percent against the dollar in the year to date and is at its weakest level in three years. A weak euro, all else being equal, should make European exports more attractive on world markets, thus potentially offsetting weaker demand from China and other key export markets.

The second reason, which should come as no surprise to anyone who has tried to follow the logic of market sentiment since the beginning of the 2010s, is the European Central Bank. The ECB has been in full-on dovish mode since 2012, when then-chief Mario Draghi pledged to do “whatever it takes” to save the single currency region. The current chatter centers around a further cut in the discount rate (which is already in negative territory) and an increase in the monthly bond-buying program, currently in the amount of €20 billion per month.

The market may have it right, and another tidal wave of easy money could head off a further downturn in the macro numbers. But it may also be wrong. The ECB’s next meeting is in March, and Mario Draghi will not be there. It remains to be seen whether new ECB head Christine Lagarde will be able to work the same magic as her predecessor. Moreover, the tensions between the austerity-loving “north” bloc of the ECB and the more dovish “south” members have not gone away at all.

Finally, there remains the unanswered question about just how far below zero interest rates can go before the unintended consequences turn ghoulish. In that respect the US Fed has much more runway for taking further policy action than does the ECB. And if Europe does fall into recession, the likely hit to investor sentiment may have Fed bankers hastily updating their own arsenal of money-printing tools.