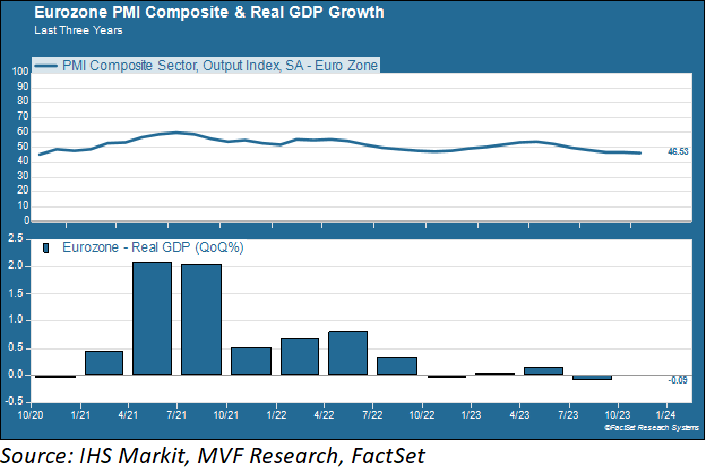

Europe is stuck in an economic rut. Don’t take our word for it. Take it from Mr. Whatever It Takes himself, former ECB chief and ex-Italian prime minister Mario Draghi, who said this week and we quote (as reported in the Financial Times from an FT Global Boardroom Conference): “It is almost sure that we are going to have a recession by year-end.” The numbers bear out Draghi’s downbeat take on things in his part of the world. Real GDP growth was minus one percent for the third quarter, while the Purchasing Manager’s Composite Index, a measure of economic health, has been in contractionary territory since the middle of this summer (a PMI reading below 50 indicates contraction, while 50 or more means expansion).

Left Behind

Draghi’s concerns about the Eurozone’s economic prospects center on the fear that the region is falling further behind both the US and China in terms of global competitiveness. The European model for much of the past decade or so could be summed up as a tripartite dependence syndrome: on the US for defense, China for trade and Russia for energy. In fairness, Europe has done a great deal to change the third part of that dependence, demonstrating since the outset of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 that it was capable of weaning itself off Russian energy flows, particularly natural gas. On the trade front, though, China’s ongoing struggles with its own economy arguably are the key reason for that recent string of underwhelming EU GDP numbers. Europe is a major manufacturer of high-value goods, and China is an all-important customer. Germany, in particular, has felt the pain of diminishing demand for its China-bound exports.

The sense of falling behind is perhaps most acutely felt in comparison to the improved fortunes of the US economy. The gap between economic output between the US and the EU is growing; in 2013, EU GDP was roughly 91 percent of the US. Ten years later, that ratio is 65 percent, and even more pronounced on a per capita basis. A look at the composition of US and European stock market indexes offers a clue as to why. About 40 percent of the MSCI EU stock index is made up of companies in the industrial, financial services and energy sectors. Information technology, where much of the growth in the last decade or more has taken place, accounts for just ten percent of the index. That is a marked difference from US indexes like the S&P 500, where tech dominates not just in the formally designated information technology sector itself, but elsewhere like consumer discretionary (Amazon, Tesla) and communication services (Alphabet (Google), Meta (Facebook), Netflix).

Chronic Underperformer

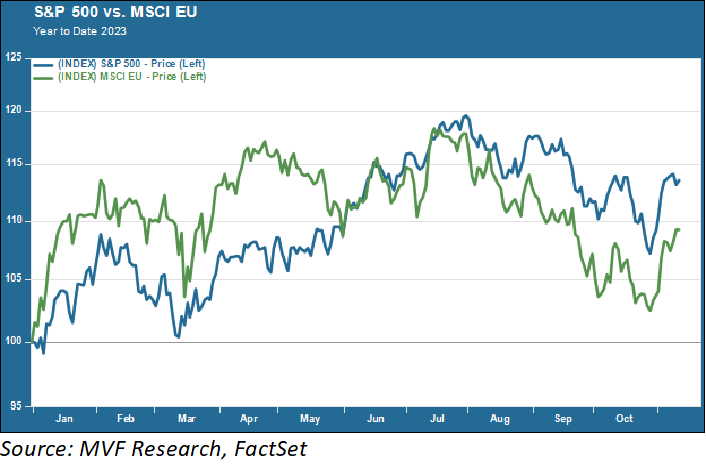

And how have those EU stock indexes been faring this year? Let’s take a quick trip back to January, when “buy Europe” was one of the big themes among the financial chattering classes (that is, when they weren’t imploring you to buy 10-year Treasuries because you were never going to see yields as high as 3.5 percent ever again…oops).

Indeed, that looked like a pretty good trade for a while, as the above chart shows. But when we take into account the picture for the full year to date, we get a good lesson in why tactical investing is usually a bad idea. What sell discipline would have convinced you to start unloading your MSCI EU shares in May, when they started going the other way and eventually did what they have done so often in the past thirty years, i.e. fall behind the US?

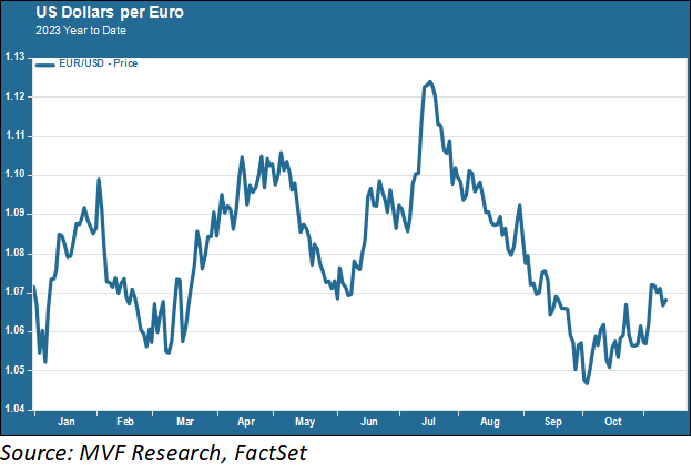

And it’s not like there was some compelling structural case to make as to why Europe might suddenly look attractive, back in January. In fact – and this tends to be true more often than not – the main catalyst for the three distinct upward moves in the EU index – in January, March and July – all coincided with a concurrent rise in the value of the euro relative to the dollar.

For a US investor with a dollar-denominated portfolio, gains or losses from overseas investments derive from the organic performance of the asset in question along with the translation value of that asset’s home currency back into dollars. As for the euro, it has gone up and down this year against the dollar but is currently sitting not too far off from where it started the year. Much ado about nothing.

As most of you know, our investment philosophy is centered on the belief that long-term discipline, based on a strategic assessment of the relative risk-return qualities of different assets, is the key to success. Trying to time effervescent short-term opportunities through tactics is more often than not bound to turn out poorly. This explains the persistence of underweight allocations to non-US international equities in our portfolios for many years now. For Europe in particular, we defer again to Draghi and his take on things at the FT conference: “The geopolitical model upon which Europe rested since the end of the second world war, is gone.” Indeed, and while we will pay close attention to how the region addresses the challenges to its global competitiveness, we do not foresee a sea change in the immediate future.