We have talked a bit in recent commentaries about the so-called “bad news is good news” phenomenon, where underwhelming economic reports actually help boost stock market sentiment. The underlying theory seems to be that as recession fears increase, inflationary concerns will subside and – punch line – the Fed and other central banks will back off at least somewhat from interest rate hikes (to be clear, this is not what actual Fed members are saying). This week we had a handful of worse-than-expected reports, accompanied by a growing chorus of downturn expectations from economists, and sure enough markets have turned in a mostly positive performance. Though, to be fair, it may not necessarily be all that surprising to see a few days of modest gains follow the unrelenting losses that have made up much of the month to date prior to this week.

Highway to the Danger Zone

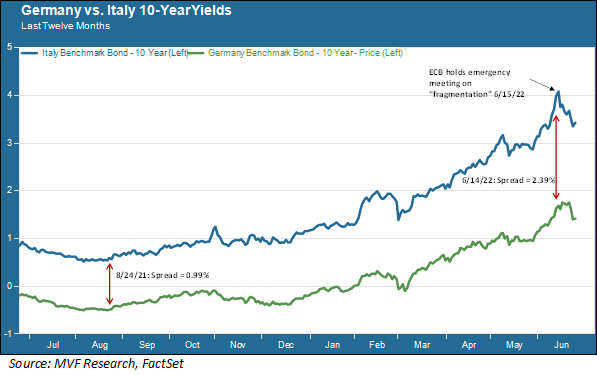

If traders are looking for bad news they need look no further than Europe, which has plenty to go around. Let’s start with bond yields. On June 15 the European Central Bank held an emergency meeting to discuss the growing problem of fragmentation between the region’s stronger and weaker sovereign credits. At the top of the list of credit concerns was Italy. Yields on 10-year Italian government bonds were topping four percent, which one ECB member (perhaps having recently watched the original “Top Gun” for the umpteenth time) called “approaching the danger zone.” The chart below shows the twelve-month performance of 10-year Italian sovereign debt against the benchmark German Bund.

At the June 15 emergency meeting the ECB announced it would commit to a “new instrument” to tackle the problem of widening spreads between stable credits like Germany and weaker sovereigns like Italy and Spain. The “danger zone” sentiment relates to the fact that Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio is considerably higher, at about 155 percent, than it was the last time credit conditions in the Eurozone approached crisis levels, in 2011-12. Back then it took three words from then-ECB head Mario Draghi – “whatever it takes” – to pull markets back from the danger zone. Draghi is no longer there (in fact, he is now Italy’s prime minister) but the ECB message of a new instrument – probably a variation of one of the bond-buying programs already in place – seemed to be enough to placate nervous bond traders. Whether that confidence lasts until the central bank gets around to explaining what this new instrument actually is – probably at their next rate policy meeting on July 21 – is another matter.

The Messaging Challenge from Hell

One big reason why the lull in widening credit spreads might not last is that any kind of new bond-buying program flies in the face of what the ECB had announced just one week earlier, at its policy meeting on June 9. In the face of what is by far the highest inflation the Eurozone has faced since it became a single currency zone in 1999, the bank announced that it was likely to raise interest rates by a quarter percent in July and then by half a percent in September. In many ways the ECB has been playing catch-up with the more aggressive shifts towards monetary tightening at the Fed and elsewhere. The rate announcement after the June 9 policy meeting was more hawkish than many economists expected. Inflation is expected to remain high for some time, particularly given that European energy markets are much more vulnerable to the disruption in Russia and Ukraine than US markets are.

The problem, then, is how to explain on the one hand that the central bank is going to take tough action on rates to bring down inflation, while on the other hand injecting more monetary stimulus into certain parts of the region to bring down already-high rates? The market places a high premium on messaging guidance from central banks. Good messaging optics have been hard to come by anywhere recently as the monetary mandarins have struggled to recalibrate their expectations about inflation and growth. But it is particularly hard for the ECB, an institution not generally known for high-caliber messaging discipline, when the underlying message itself is so potentially contradictory.

Running Low on Gas

The economic problems facing the Eurozone are not likely to improve in the near term. This week the head of German utility RWE warned that the continent will face chaos this winter if they don’t act now to establish rules on energy sharing to prepare for the likelihood of further cuts in gas exports from Russia. Gas volumes on the Nordstream 1 pipeline, a major conduit of energy from the Siberian gas fields to German homes, were recently cut by about 60 percent ahead of some scheduled maintenance on the pipeline. So far the volume cuts have not been offset by increases through other pipelines. It’s not yet time for German households to start rationing gas, say the authorities, but that time may fast be approaching. The International Energy Agency has warned that Europe needs to prepare for the possibility of a full cessation of gas supplied from Russia. In that event rationing will certainly be in the cards – hence the RWE warning to start preparing consistent rules and standards now.

Stagflation, the word that came back into vogue in 2022 after a 40-year hiatus, is still far from a certainty in the US. But the probability for high inflation coupled with low or negative growth to persist in Europe for some time seems to be increasing. After the negative shocks of war in Ukraine and China’s zero-Covid flailing, Europe perhaps more than anywhere could use a positive shock or two.