One of the big stories late last fall was the abrupt about-face turn by the Chinese government on its zero-Covid policy. Following a series of highly unusual public protests in a number of cities the government backed away from the draconian lockdown policies that had bedeviled its citizens and its economy for the better part of the year. The reopening theme caught fire among foreign investors, and suddenly China was hot again. In the last couple months of the year it was not unusual to see the Shanghai and especially the Hong Kong markets register intraday percentage moves in the high single digits.

And then suddenly it was Europe’s turn. Since November 1 last year the MSCI EU index has jumped up nearly 19 percent, well ahead of the comparatively staid 2.9 percent price gain of the S&P 500 for the same time period. An international flavor is in the air in these first early weeks of 2023. Is this the beginning of a longer-term dynamic, or a short-lived flash in the pan in the manner of so many other brief spurts of strength from non-dollar equities in recent years?

Europe, It’s a Gas

There is a connection of sorts tying together the newfound fondness for Chinese and European assets. China is the EU’s major trading partner, and its reopening (though sporadic, with Covid cases continuing to surge around the country) is good news for French luxury goods makers and German producers of high-end manufactured goods. But arguably the biggest driver of good cheer on the continent is the weather (unless you are an avid skier). Warm days and nights have been the norm this winter, with Alpine ski slopes of green and brown more evocative of May than January, and home heating bills that don’t break the bank. Europe bought massive amounts of liquefied natural gas last year, filling up its gas storage units to offset the energy disruptions proceeding from the neighboring war in Ukraine.

All of this together amounts to a reasonably valid argument that things in Europe could be a whole lot worse than they seem to be. Some economists are raising their forecasts for the EU’s economic outlook this year, although the consensus expectation is still for a recession at some point (the European Central Bank’s latest forecast still assumes a Eurozone recession starting sometime in either the fourth quarter of last year or the first quarter of this year). Observers also note that core inflation in Europe is trending at a lower pace than US core inflation, with energy prices (not a core inflation category) having been the main driver of higher prices there, while consumer demand has kept the core number higher here.

But Will It Last?

So does it make sense to push a bit more money into European equity plays? Here is where our Euroscepticism comes into play. We think the factors driving EU equity outperformance today are more of a short-term cyclical nature than a structural trend likely to persist over a multi-year time horizon. For taxable portfolios in particular that presents a headwind; even if you are right about the tactical play (and that is giant honking “if,” to be clear), the quick get in – get out leaves you with a hefty short-term capital gain. It takes some serious outperformance to more than offset the bill when that comes due on April 15.

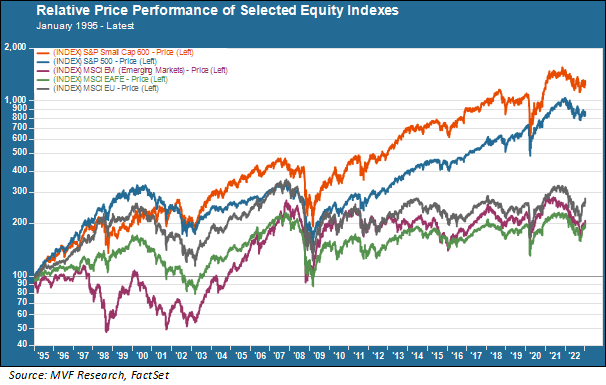

And even for qualified non-taxable portfolios that “get out” part of the equation can be vexing. We have seen pockets of outperformance for both non-US developed and emerging markets portfolios throughout the years. Over time, though, those bets have not delivered, as you can see in the chart below.

As the chart shows, over multiple market cycles starting in the mid-1990s the returns on the three non-US indexes shown (the MSCI EU, Emerging Markets and EAFE indexes in gray, crimson and green respectively) underperformed both the S&P 500 and S&P 600 Small Cap (blue and orange respectively) by a magnitude of more than three times cumulatively. Note that we express these returns in US dollars, which is what matters for a US-domiciled portfolio and thus accounts for currency translations.

We would note in addition that non-US equities tend to be more volatile in general, partly due to the added variable of currency risk, and so on a risk-adjusted return basis the US – non-US gap would be even more pronounced. The idea behind investing in a riskier asset of any nature is that, over time, those risks should be compensated for by higher returns. Such, here, is not the case.

On the other hand, small-cap domestic stocks do still seem to demonstrate at least to some degree the long-term equity risk premium the financial theory textbooks say they should. As we look ahead this year to a potential rebound in equities from the tough environment of last year, we are more inclined to see additional value from US small caps as a way to extend our risk frontier. We’ll have more to say about this in the weeks ahead.