It has been, to say the least, an exceedingly strange summer in the world of risk asset markets. Alongside a near-daily stream of general news items suggesting that the basic rules of the world as we have long known them no longer apply – from the price of money to the usefulness of an economic union to the mechanisms of political parties and so on – alongside this theater of the bizarre has been one of the most placid summers in recent memory for capital markets. Put the UK FTSE or the S&P 500 on the cover of Alfred E. Neuman’s Mad Magazine with a smugly cheesy “what, me worry?” grin and you have the mood of the moment. Intrepid event risk hunters must feel tempted to throw in the towel, head for the hills or the shore, and wake up again in a month. Those still holding onto the notion that something – anything! – may have the ability to shake markets out of their complacency could do worse than look at the brewing trouble spot of Italy’s financial system.

Siennese Waltz

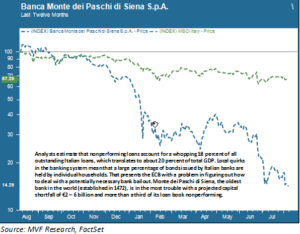

In 1472 Christopher Columbus was still 20 years away from setting sail for the New World. England was still engulfed in the Wars of the Roses. In the principalities of northern Italy, though, the cornerstones of modern finance were being laid with the emergence of a structured, institutional market for borrowing and lending. One of the institutions founded that year, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, is still in existence and as such is the world’s oldest bank. But prospects for another half-millennium of life are anything but certain. After a stress test last week showed Monte dei Paschi to have negative capital adequacy under simulated adverse conditions, the storied institution and its regulators are scrambling for a solution to avoid an ignominious end. As the chart below shows, detailing the bank’s stock price for the last year versus the MSCI Italy stock index, investors are anything but confident in their prospects.

Monte dei Paschi’s troubles are those of the entire Italian banking sector writ large: an unsustainably high level of nonperforming loans supported by unacceptably low levels of provisional reserves. The IMF estimates the size of Italy’s bad loans to be €360 billion. That is a whopping 18 percent of the country’s total volume of loans outstanding. Loan loss provisions – the reserves banks set aside to cover bad debts – are estimated to be capable of absorbing less than half that amount, leaving a €200 billion overhang on the financial system. The IMF quite rightly considers Italy’s banking system, and Monte dei Paschi in particular, to be a significant risk to global growth.

Italian for “Kick the Can”

This being Europe, of course, there is no shortage of effort being applied to prevent Italy’s bad debt problem from forcing any kind of drastic action in the here and now. There are no easy options, however, and that is partly due to some quirks in the Italian banking system. In Italy millions of retail investors – ordinary households like you and me – own debt issued by Italian banks in their savings portfolios. This makes it difficult for policymakers to contemplate a “bail-in” – a rescue plan in which the shareholders and junior creditors of the rescued institution suffer losses. Attempts to orchestrate an earlier bail-in in Italy for a handful of smaller banks was met with widespread protests and even one suicide. Matteo Renzi, Italy’s prime minister who has staked his political future on a referendum on constitutional reform this October, wants to avoid a bail-in at all costs.

The problem is that new EU rules implemented at the start of this year insist on such bail-in provisions for any recapitalization of a troubled corporation or financial institution involving state aid. EU policymakers, particularly those of a less forgiving nature in Berlin and Brussels, would be loath to bend the rules so soon after their implementation. As a result, creative minds have concocted a plan that would potentially recapitalize Monte dei Paschi with €5 billion in new capital and spin €9 billion in bad debt out into a “bad bank” arrangement, all funded by private sector investors. The deal, as it emerges, will be shopped to investors later this year. Interested parties hope that will be enough time to calm frayed nerves and avert another chapter in the ongoing Eurozone financial crisis.

Alfredo E. Uomonuovo

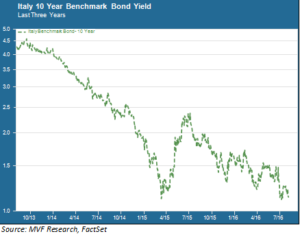

Investors in Italian sovereign debt appear uninclined to see any major event risk in Italy’s financial sector woes. Perhaps unsurprisingly for this summer of Alfred E. Neuman, the 10 year Italian benchmark bond yield is close to a three year low, as shown in the chart below.

In fact, Italian bond risk spreads relative to safe haven German Bunds have remained nearly unchanged in the six weeks or so since the Brexit shock, and a similar pattern holds for other peripheral Eurozone debt. The signal to investors would thus appear to be “no event risk here, carry on.” And it may well be that the proposed recap plan for Monte dei Paschi succeeds and keeps the wolves at bay for yet another spell of time. At the same time, though, the situation in Italy should serve as a reminder that Europe’s economic troubles are not over, and the future of the single currency union is not a given. The banking sector will not fundamentally improve until economic conditions on the Continent facilitate an environment where some measure of normal borrowing and lending activity can occur. In this most unruffled of capital market summers, one is always well advised to remember that calm seas can give way to tempests in the blink of an eye. Kicking the can down the road is fine, but all roads have an end.