The Fed did the right thing yesterday. Below trend inflation, modest wage growth, tepid productivity and sub-80 percent capacity utilization all point to a US economy that, while growing, is far from running hot. The urgency for an immediate rate hike simply was not there. Given the elevated threats evident elsewhere in the world, why risk it? That was the clear message in the communiqué which accompanied yesterday’s FOMC decision to leave rates where they are and live to fight another day. By explicitly calling out “recent global economic and financial developments” Yellen & Co. articulated the reality that what happens elsewhere in the world can have a direct impact on US prices and jobs, the twin components of the Fed’s mandate.

Data-Driven vs. Time-Driven

But the decision to stand pat at zero lower bound carries its own set of risks, first and foremost of which may be the Fed’s own credibility. The lead-up to the September meeting was particularly confusing. On the eve of the announcement the professional community was – at least according to the received wisdom – about evenly split as to whether or not there would be a rate hike. Fed funds futures markets seemed to be pricing in no action, but the 2 year Treasury was yielding over 80 basis points, a 52 week high, reflecting at least some degree of rate hike expectations (the 2 year promptly retreated back below 0.70 percent following the announcement). Observers were having trouble reconciling two somewhat conflicting positions: the “data-driven” mantra invoked by nearly all FOMC members in their various public comments, and the time stamp of “later this year” suggested by Chairwoman Yellen in previous comments, back before the Shanghai Composite began its nosedive this summer.

That earlier time stamp comment was what gave the September meeting such a frisson of breathlessness, being one of only two remaining FOMC meetings this year to be followed by a press conference (the next meeting, in October, will not include a press conference where Yellen could articulate the reasoning behind any action taken and thus is deemed a less likely venue for such action). In the wake of yesterday’s decision, we now know that data trumps the calendar, and we know that the data set extends well beyond US borders. What remains unknown is how those “global economic and financial developments” will specifically factor into the calculus going forward. Is the Fed now central banker to the world? Yes, to the extent that international growth rates and currency bourses affect US jobs and prices, and therefore domestic monetary policy. What actual global developments need to take place for the Fed to be confident about moving forward? That remains to be seen. The waiting game is, if anything, foggier today than it was leading into the September meeting. That has the potential to further roil already jittery asset markets as we head into the final quarter of the year.

Growing Pains

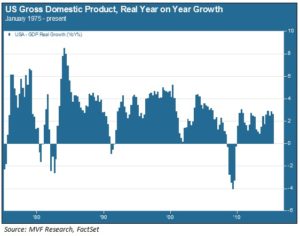

Behind the angst about when rates will start rising is a deeper concern about growth. For all the unconventional firepower central banks around the world have thrown at the problem, the fact remains that global growth is well below trend. Europe is still struggling to maintain positive growth, China’s actual – as opposed to published – growth rate is a deepening mystery and many key emerging markets are in outright contraction. In this environment the burden of global growth engine has fallen on the US. The problem is that our own growth is below trend and will likely remain so without a more robust pace of activity elsewhere in the world. Consider the following chart, showing real year-on-year US GDP growth for the past forty years, going back to 1975:

Average baseline trend growth today is lower than at any time in the past forty years. Now, resumed growth elsewhere in the world could help reverse this trend. Many of the largest companies that make up the S&P 500 derive more than half their total revenues from markets outside the US. As those markets grow, so do our own fortunes. This is why those “global developments” are important enough for the Fed to explicitly call them out. If the current growth malaise is cyclical – and if keeping rates historically low helps us work through the cycle without falling back into recession – then one could reasonably expect trend growth to turn back up.

Of course, there is no certainty that the current lack of growth in the world is cyclical. There is no shortage of opinion out there that “winter is coming”, to use the popular Game of Thrones vernacular. This view holds that the downturn in world output is structural, not cyclical, and likely to be with us for some indefinite time to come. The Fed’s credibility likely hangs in the balance as to which of these views will ultimately prove to be correct. Given what we know today, though – and much as we would like to see conditions normal enough to move away from zero lower bound – holding off on rates in light of elevated economic risks was in our opinion the right thing to do.