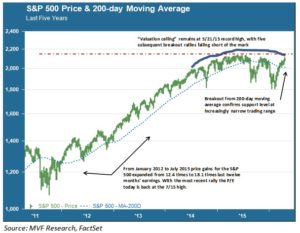

The Passover holiday starts this evening, and children in Jewish households around the world will be preparing for a traditional rite of passage in reciting the Four Questions to their elders. Investors watching the two month-long rally in equity markets may well have a question of their own: Why is this rally different from all other breakout rallies since the S&P 500 reached an all-time high of 2130 nearly one year ago, in May 2015? To put it a different way, is there anything plausible to suggest a sustained move above a fiercely resistant valuation ceiling? After the three year-plus multiple expansion rally topped out last year there have been five upside breakout attempts that have fallen short, including the current one thus far. The chart below illustrates this topping-out effect.

Tiptoeing Over the Low Bar

Much of the current focus is, rightfully, on first quarter earnings. There are two ways to interpret the results that have come in so far (about 27 percent of all S&P 500 companies have reported Q1 earnings as of today). The first is the expectations game: a number of firms thus far have managed to clear an exceedingly low expectations bar. Back in December, the consensus among analysts was that earnings per share growth would be more or less flat for the first quarter. Today, the same analysts expect Q1 EPS to decline by nine percent from their levels one year ago, when all is said and done. So all that a company has to do in order to give the market an “upside surprise” is to report earnings slightly higher than these sharply reduced expectations.

We have seen this reduced-expectations narrative play out among early reports in the financial and metals & mining sectors, two of the more beaten-down industry groups of late. For example the market takeaway from JPMorgan Chase, which led off earnings for the major banks last week, could be summed up thus: “bad, but could have been worse.” Bank stocks rallied sharply following the JPMorgan release, and were no less giddy a week later when Goldman Sachs reported a decline of 56 percent in net income from the period one year ago. If bad news is not awful news it must be good news, the convoluted logic seems to go.

Math Is Still Math

The second way to interpret Q1 earnings results is to ignore the Kabuki-like theatrics of the expectations game and point out that, however you want to frame the context, low earnings are still low earnings. Stocks are therefore still expensive. At the beginning of 2012 the ratio of the S&P 500 price index to average earnings per share for the last twelve months (LTM P/E) was 12.4 times. Investors would pay $12.40 for each dollar of average per share earnings. Over the subsequent three and a half years the LTM P/E ratio jumped from 12.4 times to 18.1 times – a “multiple expansion” rally where prices grow faster than earnings.

Today, despite two market corrections of more than 10 percent and the repeated failure to regain last year’s high water mark, the S&P 500 is as expensive as it was a year ago. It is more expensive than it ever was at the peak of the previous bull market of 2003-07. It is even dearer on a price-to-sales (P/S) basis; the current LTM P/S ratio of 1.8 times is the highest this ratio has been since the immediate aftermath of the late-1990s tech bubble.

Animal Spirits, to a Point

The fact that the market remains expensive does not necessarily preclude a breakout to the upside into new record high territory. Stranger things have happened; asset markets are the stomping grounds of John Maynard Keynes’ “animal spirits” far more than they are the purview of the fictitious rational actors of economics textbooks. The vague but often telling indicator of investor sentiment seems tilted to the upside. The question, though, is how sustainable a strong upside breakout would be in the absence of improvement in corporate earnings prospects.

We are unlikely to see the earnings math for Q1 make much of a compelling growth case. It remains to be seen whether some of the headwinds that have clipped sales and earnings prospects of late will abate further into the year – perhaps driven by a softer US dollar and a demand pickup in key consumer markets. Until then, we tend to believe that this rally is not much different from the four post-high rallies which preceded it, and that it would be a good idea to keep one’s animal spirits in check. Not in a defensive crouch, but in check.