Happy (Fiscal) Holidays

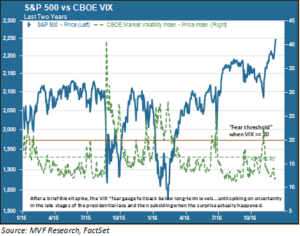

Opinions among the politico-financial commentariat appear to be converging on the basic idea that “fiscal policy is the new monetary policy.” Out with the obsession over FOMC dot-plots, in with infrastructure! Does a more robust fiscal policy, if in fact implemented, presage a structural bump-up in GDP? The stock market seems to think so, with a strangely high degree of conviction, as illustrated in the chart below.

This chart, one of our periodic favorites, shows what we like to call the “risk gap” between stock prices (the solid blue line showing S&P 500 price performance for the past two years) and volatility (the green dotted line shows the CBOE VIX index, the market’s so-called “fear gauge”). The wider the risk gap, the more complacent the market. As of late the gap has turned into a chasm, with stock prices setting all-time highs on a near-daily basis while the fear gauge slumbers at or near recent lows, and well below the threshold of twenty indicating a high-risk environment.

The takeaway from the chart would appear to be this: not only are we absolutely, positively going to get a bracing jolt of stimulative fiscal policy in the near future, but that new policy is going to translate into higher GDP growth, higher wages and prices, and who knows what else. Maybe a groundbreaking new proof for Fermat’s last theorem?

If you kept your nerve during the seven day run-up to last month’s election (where you see that big stock price dip and brief spike in the VIX), then you are no doubt pleased as punch that Mr. Market decided to react thus. But you may also be concerned about whether this reaction is a rational assessment of the impact of future fiscal policy, or alternatively a sugar high that will leave in its wake a sensation not unlike overindulging in Krispy Kremes.

Three Pillars of Fiscal Wisdom

The fiscal policy measures being lobbed around Washington think tanks and spin rooms these days fall into three broad categories: taxes, regulations and infrastructure. Call them the Three Pillars of fiscal policy in Paul Ryan’s brave new world of one-party rule. As we noted above, the market’s near-immediate response to the prospect of the Three Pillars was ebullient optimism. This attitude is partly understandable. After all, we have had to endure eight years of gridlock in Washington during which very little got done. Central banks, which did all the heavy lifting during this time, are understandably receptive to the prospect of some burden-sharing.

But two questions pose themselves. First, how much of whatever comes out of the abstract Three Pillars and into actual policy will be stimulative? Second, as Fed Chair Yellen herself has asked, how much stimulus does the economy even need? Job growth is close to what economists typically regard as “full employment.” Moreover, despite a somewhat weaker wage figure in the last batch of jobs numbers, hourly earnings have trended above core and headline inflation for the last year. GDP in the third quarter was above expectations, and even the long-beleaguered, all-important productivity number beat expectations in Q3. These are not exactly conditions screaming out for a redoubling of stimulus (though, to the point made by many central bankers, when it does become time for more stimulus in the future, it would be preferable for the burden to be shared between monetary and fiscal sources).

Given that the economy is, in fact, not falling off a cliff, by nature austerity-loving Republicans in the House are likely to push back on initiatives that add significantly to the budget deficit. Tax cuts will always be a priority over new spending on the right-hand side of the Congressional aisle. Of the Three Pillars, tax cuts are probably the most likely to be first out of the gate. But even here, as we read the (admittedly confusing) tea leaves of current chatter, the outcome is not likely to be as simple as was the last batch of significant cuts under George Bush. Not only individual and corporate taxes are under consideration, but some kind of a value-added sales tax as well, as a partial offset measure. Strangely a VAT tax – generally considered regressive – seems to have a measure of Democratic support.

Dots, Unconnected

We will have quite a bit to say about the progress, or lack thereof, of the Three Pillars in forthcoming commentaries. Where we always want to take the discussion, though, is back to how these measures ultimately connect to anything that drives actual cash flows for publicly traded companies. Connecting these dots is what helps us understand whether there is anything fundamental behind temporal stock price movements or not.

Right now our assessment tends more towards the “not.” That “risk gap” illustration above strikes us as being unsustainable. Either volatility will pick up at some point – most likely as the pre-inauguration honeymoon winds down and the real business of governing looms large – or markets will resume the kind of drift patterns along a trading corridor such as we saw for much of 2015 and 2016.

A period of corridor drift could be preceded by a sizable pullback of five to ten percent, such as the ones we experienced in August 2015 and January 2016. We tend to think that such a pullback would more likely be the result of an external surprise – another plunge in the renminbi, say, or even a geopolitical shock from a global trouble-spot – rather than anything directly connected with the still-healthy U.S. economy. While we don’t see the makings of a sustained downturn ahead, it is worth remembering that stock price valuations remain at decade-plus highs.

Only a sharp upturn in corporate earnings in the coming quarters will supply the justification needed to be comfortable with those high valuations. That upturn, should it come, will be the result of continuing improvements in productivity and a revival of global demand. Not from a fiscal stimulus program that may or may not happen.