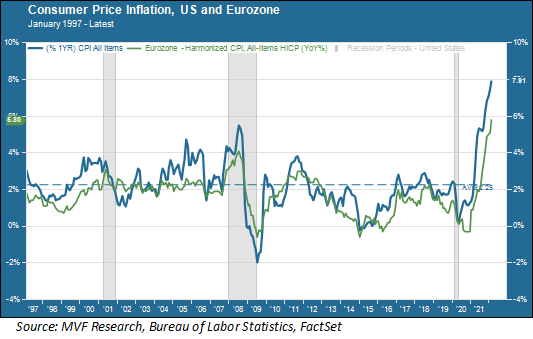

The war in Ukraine continues in its merciless ways, asset markets continue to be buffeted this way and that by the supercilious rumors that drive short-term trading strategies, and policymakers around the world continue to grapple with what the effect of the war will be on inflation and economic growth. Those two variables – inflation and growth – are at the center of the tension between central bankers who seek decisive action on containing spiraling prices and those who are worried about how higher interest rates could threaten a reversal of recent global growth trends. Central bank meetings in Europe and the US are taking place with a fresh set of data showing the highest levels of consumer inflation in recent memory.

The Bundesbank Calls the Shots

First up was the European Central Bank, which met yesterday amid some economists’ expectations that the bank’s recent dovish tilt would prevail with a message of caution against unwinding economic stimulus too quickly. Perhaps those economists were forgetting to take into account that Germany’s Bundesbank, the most influential of the national central banks that make up the Eurozone, has a new head. Joachim Nagel, the newly-minted Bundesbank president, wasted no time in asserting his organization’s traditional bias towards strict efforts to control prices. Never mind that the hyperinflation of the Weimar Republic happened one hundred years ago – it still burns deep in the veins of every German central banker.

The hawks prevailed at the ECB yesterday, reportedly by a margin of 15 to 10, which means that the current stimulus provided under the auspices of the Asset Purchasing Program (APP) will start to wind down in April, with monthly purchases falling from €80 billion to €40 billion, then €30 billion in May and €20 billion in June. Net purchases will cease entirely by the third quarter if there is no evidence by then of a meaningful fall in inflation. Not surprisingly, Eurozone bond prices fell in response to the news.

The concerns on the dovish side about growth are unlikely to go away, however. The IMF will be publishing its updated forecast for global growth in the coming weeks, and yesterday the organization’s head, Kristalina Georgieva, expressed confidence that the 2022 projection will be coming down from the 4.4 percent predicted in the most recent outlook back in January. The real global growth rate in 2021 was 5.9 percent. Growth is a larger concern in Europe than in the US, for now, due to the fact of the region’s closer entanglement with the collapsing Russian economy, particularly in the field of energy. While the IMF’s Georgieva does not see a Eurozone recession as a probable event in 2022, she did observe that recessionary concerns are higher now as a result of the conflict in Ukraine.

Over to Powell and Company

Next week it will be the Fed’s turn, as the Federal Open Market Committee prepares for its Tuesday-Wednesday conclave. The March Fed meeting will come with the Summary Economic Projections that provide a window into what the FOMC members are thinking about economic trends and interest rates. The prevailing market consensus is that the Fed will raise rates five times this year in 0.25 percent increments, starting with next week’s meeting. The SEP data will give that consensus some factual context (though we should note that there is nothing officially binding in the numbers, as they only reflect individual members’ thinking at the time).

We expect that the tone from the Fed meeting will be similar in nature to that of the ECB this week: fighting inflation is job number one, and concerns about economic growth will remain secondary. Just this week Treasury Secretary Yellen backed off from comments earlier this year that inflation could be down closer to two percent by the end of the year, with more persistent disruption from energy prices and supply chain problems proceeding from the trouble in Europe. As we have maintained in recent commentaries, there is very little likelihood of the US experiencing a recession any time soon. But policymakers are already starting to talk about a “soft landing,” which is bureaucratic-speak for expectations of diminishing growth. Jay Powell will no doubt be pushed hard by reporters at the post-FOMC press conference about his own views about landings – soft, hard or otherwise.