Sweden, France and Germany are all in the news this week, and not just because they all have teams competing in the quarterfinals of the Women’s World Cup (we are hoping that by the time this article comes to press one of those three – France – will be en route to exiting the tournament at the hands of our own awesome US women’s soccer team). No, the other noteworthy news is that all three countries are now card-carrying members of Club Wonderland, the ever-expanding coterie of nations with benchmark 10-year interest rates trading in negative territory. Investors, it would seem, cannot get enough of the opportunity to pay for the “privilege” of lending to sovereign nations. And the looking glass world gets weirder still: in Denmark (which, by the by, does not have a team contending in the World Cup) there are stories of financial institutions offering mortgages to homebuyers with negative interest rates. You heard that right – buy a home in Copenhagen and get paid by the lender at the same time. Pretty sweet, however insane-sounding to anyone schooled in the quaint old ways of traditional financial theory.

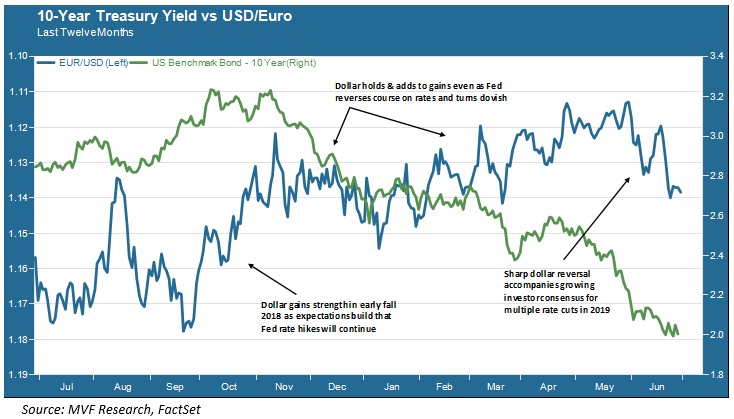

Back here at home we remain, for the present time at least, on the real-world side of the looking glass. Interest rates are low, with the 10-year Treasury yield just barely holding ground at two percent, its lowest level since November 2016 (the benchmark has come full circle since launching itself on that absurd “infrastructure-reflation trade” that was all the rage in the aftermath of the US elections that month). Two percent isn’t much – it’s basically zero purchasing power on an inflation-adjusted basis. But the logic of holding the world’s safest fixed income security and still getting paid interest seems pretty solid compared with the alternative of investing in Eurozone Wonderland bonds. Right? And that would seem to at least partially explain why the US dollar has remained strong even while US interest rates have plummeted in recent months. The chart below shows the greenback’s current trend versus interest rates.

The dollar-euro exchange rate would seem to be a useful point of analysis for considering interest rate trends in Real World USA and Wonderland Europe. As the Fed steadily executed its dovish U-turn over the course of the first half of 2019, the dollar remained firm – the rationale being, of course, that non-US investors still preferred to hold US assets (thus supporting the value of the dollar) rather than play the loser’s game of negative interest rates. So far so good. What has taken some currency traders by surprise, though, is a fairly pronounced trend reversal for the dollar that started in late May and intensified after the most recent FOMC policy meeting last week. Could the dollar be in for a longer period of weakness?

What would a bear case for the dollar look like? Here it’s more a question of relative, rather than absolute, price movements. The European Central Bank remains dovish – nobody expects any kind of coordinated interest rate hike policy over there any time in the foreseeable future. But there’s not a whole lot more downside for rates either – unless we completely jump through a 4-D hyperplane and into a parallel universe where negative interest rates in the low-mid single digits are the norm. In the US, on the other hand, there are nine downward steps (of 25 basis points each) if the Fed wants to take us back to the zero lower bound where the Fed funds rate resided through most of the first half of this decade. And the consensus for a dramatic series of imminent cuts is remarkably strong right now. Three by year-end and maybe as much as a full 50 basis point move in July is the odds-on wager in the Fed funds futures market.

So it would be the relative magnitude of the Fed’s dovish turn, versus the more limited tools available to the ECB, that could spark a more sustained downward move in the dollar. In so doing it would give an immediate boost to the non-US asset holdings in domestic investors’ portfolios. If – and we still think this is a big if – those rate cuts go ahead to the extent the market believes.

But there is also a reasonable case to make that the market has gotten ahead of its skis on this rate cut consensus. Remember – there is still no hard evidence that a somewhat slower pace of growth in the US will lead to a recession in the near term. In a matter of days – come July – this current economic growth cycle will become the longest on record in the US. The trade war – everyone’s go-to excuse for why the Fed would take drastic action on rates – ebbs and flows with a daily barrage of superficial headlines from sources lacking in credibility. Meanwhile, safe-harbor assets like US Treasuries seem rather unlikely to lose much of their luster in a market environment with risk-off inclinations. Long story short: taking an overly bearish position on the US dollar could prove painful in the weeks and months ahead.