China’s slowdown, cash-strapped emerging markets, the negative interest rate contagion – news from the world economy has been almost uniformly negative for much of the past twelve months. The bright spot amid the gloom has been the relatively upbeat US economy, the strength of which finally convinced the Fed to nudge up interest rates last December. At that time, based on the available data, we concurred that a slow liftoff was the right course of action. But a growing number of macroeconomic reports issued since call that decision into question. From productivity to durable goods orders to real GDP growth, indications are that the pace of recovery is waning. Not enough to raise fears of an imminent recession, but enough to stoke the flames of negative sentiment currently afflicting risk asset markets around the world.

Mary Mary Quite Contrary, How Does Your Economy Grow?

Jobs Friday may be the headline event for macro data nerds, but in our opinion Productivity Wednesday was the more significant event of the week. The Bureau of Labor Statistics release this past midweek showed that fourth quarter 2015 productivity declined by three percent (annualized) from the previous quarter. Now, productivity can be sporadic from quarter to quarter, but this week’s release is part of a larger trend of lackluster efficiency gains.

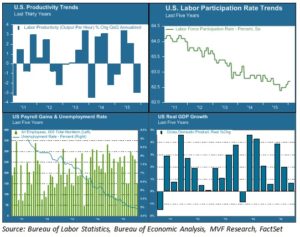

As measured by real GDP, an economy can only grow in three ways: population growth, increased labor force participation, or increased output per hour of labor – i.e. productivity. Unfortunately, none of these are trending positive. The chart below offers a snapshot of current labor, productivity and growth trends.

Labor force participation (upper right area of chart) has been in steep decline for the past five years – an outcome of both the jobs lost from the 2007-09 recession and the retirement of baby boomers from the workplace. This decline has helped keep the headline unemployment rate low (blue line in the bottom left chart) and also explains in part the anemic growth in hourly wages over this period. This trend is unlikely to reverse any time soon. If real GDP growth (bottom right chart) is to return to its pre-recession normal trendline, it will have to come from productivity gains. That is why the current trend in productivity (upper left chart) is of such concern.

Of Smartphones and Sewage

The last sustained productivity surge we experienced was in the late 1990s. It is attributed largely to the fruits of the Information Age – the period when the innovations in computing and automation of the previous decades translated into increased efficiencies in the workplace. From 1995 to 2000 quarterly productivity gains averaged 2.6 percent on an annual basis. The pace slackened in the first decade of the current century. In the first five years of this decade – from 2010 to the present – average quarterly productivity growth amounted to just 0.6 percent – more than three times slower than the gains of the late 1990s.

Is that all we can expect from the Smartphone Age? Or are we simply in the middle of an innovation gap – a period in between technological breakthroughs and the translation of those breakthroughs to actual results? It is possible that a new growth age is just around the corner, powered by artificial intelligence, virtual reality and the Internet of Things, among other inventions. It is also possible that the innovations of our day simply don’t pack the same punch as those of other ages. Economist Robert Gordon makes a version of this argument in his recent book The Rise and Fall of American Growth. Gordon points to the extraordinary period of growth our country experienced from 1870 to 1970 – growth delivered largely thanks to the inventions of electricity and the internal combustion engine – and argues that this was a one-off anomaly that we should not expect to continue indefinitely. What would you rather live without – your Twitter feed and Uber app, or indoor plumbing?

We don’t necessarily agree with Gordon’s conclusion that nothing will ever again rival electricity and motorized transport as an economic growth driver. But we do believe that the growth equation is currently stuck, and the headline data we have seen so far this year do nothing to indicate its becoming unstuck. Long term growth is not something that drives day-to-day fluctuations in asset prices. But its absence is a problem that is increasingly part of the conversation about where markets go from here. Stay tuned for more Productivity Wednesdays.