Here in the US it’s easy to get caught up in the minutiae of the Fed: what did Bullard say at that luncheon the other day? What about Brainard in her comments at the San Fran tech conference? Is a 50 basis point rate hike on the table for March? What does that blockbuster jobs report that just came out today mean in terms of how it plays into Powell’s calculations?

All important points, no doubt, but sometimes it’s helpful to remember that there are other central banks in the world which, while perhaps not as influential as the Fed, still exert a meaningful impact on global credit markets. We saw evidence of that this week. The Bank of England raised the bank rate, its long-standing monetary policy tool, for the second straight time. Moreover a sizable minority of four voting members wanted more action in the form of a 50 bps increase (the majority voted for 25).

Last of the Doves

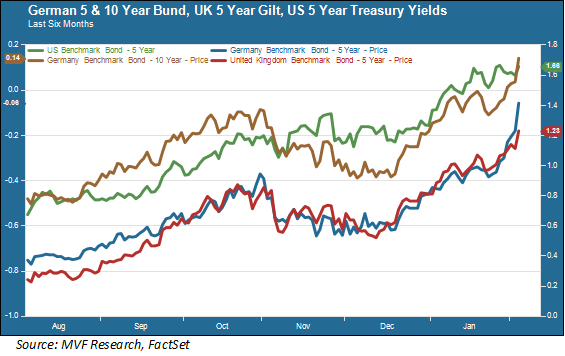

Markets had expected the BoE move, but they were caught a bit off guard by a surprising pivot by the European Central Bank, widely seen as the most dovish of major central banks in wanting to hold off talk of any rate hikes until after 2022. During the post-meeting press conference ECB president Christine Lagarde noted that inflation rates were “tilted to the upside” and “getting much closer to target.” The bond market was listening. Rates on Eurozone-area sovereigns surged in the immediate wake of the press conference.

“Tilted to the upside” might be the understatement of the year when it comes to Eurozone inflation, which had registered its highest level ever the day before the ECB meeting. The Consumer Price Index jumped to 5.1 percent, beating economists’ forecasts of a 4.3 percent increase. In all fairness, the Eurozone as a single currency union has only been around in practice since the adoption of the euro in 1999 (the currency didn’t actually start circulating in public until 2002). So “highest ever” doesn’t mean the same thing as if it were, say the US CPI. But still – inflation is clear and present. Also this week the unemployment rate in the eurozone fell to a record low of seven percent, suggesting that a hot labor market could also add to pricing pressures.

Finally, of course, there is the sword of Damocles hanging over the continent’s energy prices in the form of the Ukraine situation and resulting sanctions if Russia goes ahead with an invasion. Europe gets about 40 percent of its total energy supply from Russia, and prices for heating oil and natural gas are already sky-high. Going into this month’s meeting, the ECB had been determined to forswear any talk of rate hikes in 2022. Lagarde’s sudden post-market pivot has sent bonds in a new direction.

End of the Calm for Credit Markets?

The relatively calm conditions in US credit markets so far this year have been a distinct contrast to the volatile performance of equities. We have found this to be somewhat surprising, given how negative yields are on an inflation-adjusted basis. But conditions might be changing. The seven-day period to this past Wednesday saw the ninth biggest outflow on record from investment grade and high yield bonds, in the amount of $10.3 billion. The iShares iBoxx High Yield Corporate Bond ETF fell nearly two percent on the same day that the ECB did its surprise about-face. That’s not a rout by any stretch, but instability in higher-risk corners of the credit markets could amplify the already-high jitters present in equities.

For now it’s wait and see, with at least three major central banks – the Fed, Bank of England and ECB – pretty much in play every time they meet for monetary policy formulations in the months ahead. We like to tell our clients to pay attention to the bond market if they want to know what’s in store for stocks. So far this year that hasn’t been great advice – but that could be changing.